Writing Excerpt: Organizational Feature for the San Diego Chargers

Who I Ain’t

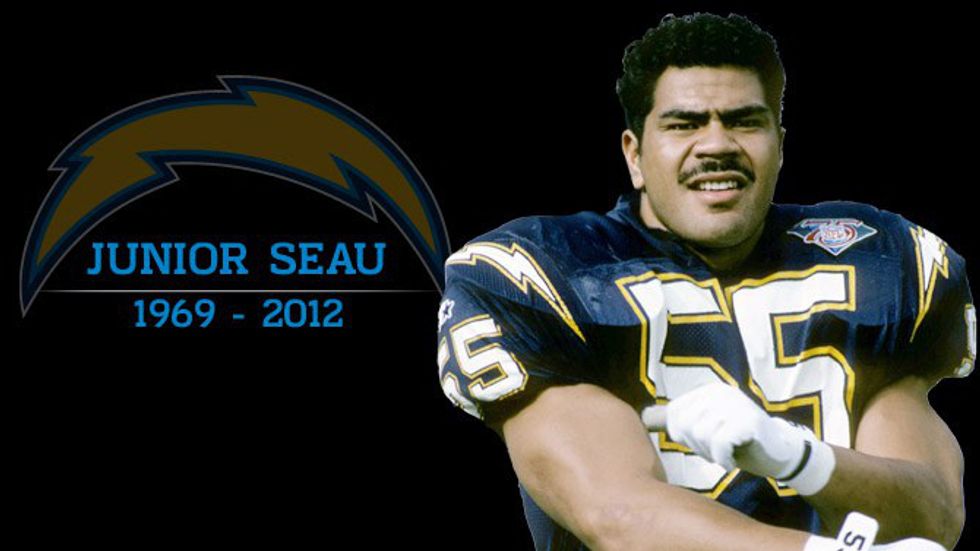

“You mean more than you know and are missed but not forgotten.” This was written on a note left at the gravesite of the former Chargers linebacker and local hero, Junior Seau. He grew up in San Diego, went to Oceanside High School, played at USC, and was drafted by the San Diego Chargers. It’s hard to be more local than that. During his life, he touched countless lives with his passion, kindness, and ability to form relationships with just about anybody, calling them “buddy” and “friend”. Seau’s mother used to tell him, “Go out and make happy!” He was laid back, handsome, and as an ESPN memorial article states,“he was San Diego.” After his death, Seau became an icon.

Suicide is a painful word. A guilty word. On May 2, 2012, Seau was found dead in his home in Oceanside with a gunshot wound to the chest. The lyrics of “Who I Ain’t”, a country song co-written by Jamie Paulin, Seau’s friend, were found in his kitchen.

“I’ve tried to be the man I should, but sometimes I fall short.

I’m not a man of anger, I never meant to hurt no one.

My only hope for forgiveness when the good Lord calls my name…

Is that he knows who I am…

and who I ain’t.”

His autopsy revealed no alcohol or drugs, save for zolpidem, a sedative used for treating insomnia. The Seau family donated his brain tissue to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. In January of 2013, the institute revealed that Junior Seau had suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) as a result of “exposure to repetitive head injuries.” The results of the study have made Seau one of the many faces of CTE among NFL players, but he will always be remembered in San Diego as the man who brought enthusiasm and joy to the city for 13 years.

The Chargers organization can be traced back to a man named Barron Hilton, who purchased the Los Angeles franchise of the new American Football League as a 32-year-old business mogul in 1959. An avid supporter of USC football, he decided on naming his team the “Chargers” after hearing the yells of “Charge!” while watching the Trojans play. As the 1961 season approached, Hilton saw that the Chargers were struggling to compete with the Rams for fans. He decided to move the organization 120 miles south to San Diego, where it has been ever since. A fundraising partnership with local newspapers helped raise money for a new stadium in 1965, which went through several name changes. The San Diego Stadium became Jack Murphy Stadium, which became Qualcomm Stadium, the team’s current home. Hilton sold the majority of his shares of the team in 1966, taking on his father’s former role as the president of the Hilton Hotels Corporation.

The early days of the San Diego Chargers were filled with great success. The team was talented, winning four AFL championships in its nine years in the league. Then came 1970 and the AFL-NFL merger. Forty-six long years later the Chargers had yet to win another championship. Back in 1990 however, the city was given hope. With the fifth pick in the NFL draft, the Chargers selected a phenomenal athlete and hometown kid, an Oceanside High alumnus and first team All-American.

Junior Seau quickly grew in popularity and respect among his teammates, getting the nickname “Tasmanian Devil” for his wild, uninhibited style of play. His daughter Sydney describes him as being “relentless, hard-hitting, passionate, and unstoppable.” These characteristics led to over 1,800 tackles, 50 sacks, 12 consecutive Pro Bowls, and a Defensive MVP award. He brought the Chargers to their first and only Super Bowl appearance in 1994. Today the Chargers are still aiming for the chance to play in their second Super Bowl, and are going through a period of negotiations with city legislators and the NFL to see if they will remain in San Diego after the current season. Playing through the pain was part of Seau’s gritty legacy, as he endured pinched nerves, broken hands, ankle sprains, and more. One story tells of the linebacker breaking his hand while making a tackle, then refusing to undergo an X-ray, saying, “I know it’s broke. We don’t need to X-ray it.” He proceeded to play the rest of the game with no complaints. He played hard and he played fair, but under no circumstances would he take it easy on an opposing player. In Seau’s own words:

“To strike your will on another player in hopes that the player quits on you and allows you to do what you need to do at your pace -- that's the name of the game, to have your guy surrender. And once he surrenders, you don't stomp on him; you go on to the next guy.”

In addition to his on-field heroics, Junior Seau was a deeply relational man. His daughter also described him as “caring, gentle, hilarious, and generous.” Al Davis, the owner of the Oakland Raiders, had good reason to hate Seau for all the years of beating up on his team. However, after the men spoke for two hours, Davis referred to Seau as having an alter ego. “He was just arms wide open. I valued his friendship because he was very special.” Eric Olsen, now a lineman for Cleveland, relates his own Junior Seau story. Seau came to visit his high school, and challenged any of the young men to face him one-on-one. A terrified Olsen volunteered, only to see Seau give him a wink and allow himself to be thrown down by the high schooler. In Olsen’s words: “I can't even tell you how good I felt at that moment. It changed me forever.” That one moment began his own journey to the NFL. Seau’s selfless actions are at the core of who he was as a person, and the person he was is far more important than the football player he was.

“My only hope for forgiveness when the good Lord calls my name… Is that he knows who I am… and who I ain’t.”

Junior Seau, your legacy is sprawling. Your words and actions have influenced thousands. You have led others to become better men and women. Junior, you ain’t forgotten.