Over the course of its sixteen-year run, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart developed into a cultural icon for its “fake-news” journalism and comedic sensibilities. At its helm sat Jon Stewart, who took on multiple roles and identities in the eyes of his large audience, both at his desk on The Daily Show and outside of the studio. In all of his roles, Stewart’s Jewish identity exerts a profound influence on the image he represents. Jon Stewart is the prime example of Jewish assimilation into secular America: his public persona balances culturally Jewish and irreligious, liberal American values.

Born Jonathan Stuart Leibowitz, he grew up in a “typical well-educated middle class Jewish family” in Lawrenceville, New Jersey and attended a Jewish preschool in a neighboring town. His paternal grandfather was a cab driver, and his great-grandfather was an Orthodox Jewish immigrant who owned a shoe store on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He was the only Jewish student at his middle and high schools. In a 2002 interview with Tad Friend of The New Yorker, Stewart recalled taunts from his peers, noting, “I didn’t grow up in Warsaw, but it’s not like it wasn’t duly noted by my peers that that’s who I was – there were some minor slurs.” Some of them included “Leibotits” and “Leiboshits,” stirring an early discomfort with his ethnic last name. Nevertheless, he graduated from high school in 1980 with the “Best Sense of Humor” superlative but without intentions of pursuing comedy professionally.

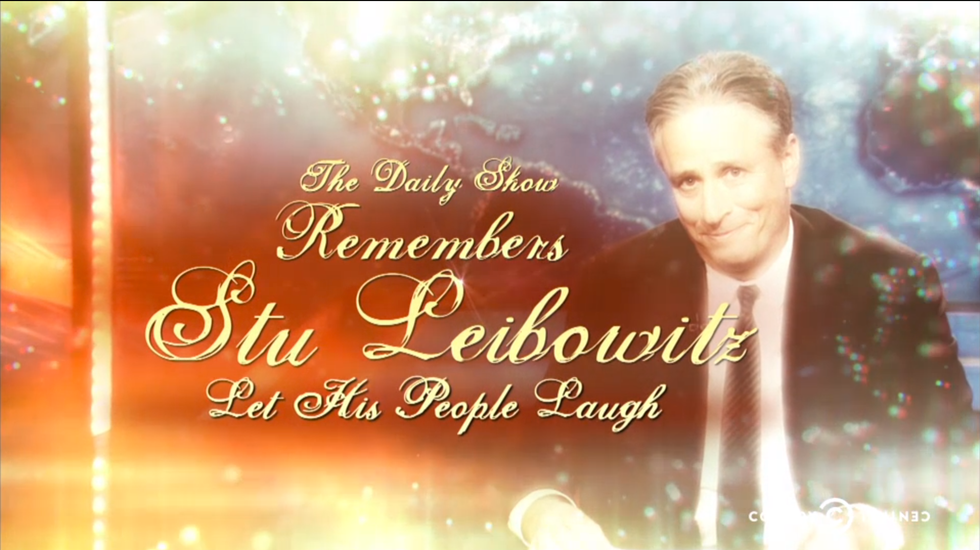

His first (failed) attempt at stand-up comedy was at The Bitter End comedy club in the West Village in Manhattan in 1987. His opening joke? “What do they call lunch hour in the diamond district when all the Hasidim are causing a traffic jam in the streets? Yidlock.” He traces the start of using “Stewart” as his last name to this show as well; when the emcee had trouble pronouncing “Leibowitz,” he decided to use an alternate form of his middle name instead. He legally changed his name to “Stewart” in 2001, but his birth name is often mentioned in discussion about him and his career. Multiple small movie and television gigs later, Stewart was selected to replace Craig Kilborn on The Daily Show in 1999. After the attacks on September 11th, 2001, Stewart’s poignant response captivated his audience and is often referenced as the point at which Stewart himself took on a greater value for its viewers.

Jews are often portrayed in media as self-deprecating, as outsiders, and as neurotic mothers. Various figures have tried to capture the essence of how Jewish comedy in particular differs in its portrayal of Jews. Rob Kutner, a past writer for the Daily Show, noted in 2008 that “the general audience seems to get the kind of Jewish approach of throwing spitballs from the outside at the government and authorities, the skepticism.” This take on Jewish humor also connects to the stereotype that Jews are cynical and often complain. Michico Kakutani of The New York Times find a more optimistic tone in the humor on The Daily Show, noting that “its keen sense of the absurd is perfectly attuned to an era in which cognitive dissonance have become a national epidemic.” In Kakutani’s view, the tendency to bemoan authority is something that the whole country has adopted; it is no longer unique to the Jews, as the Rabbis quoted earlier believe.

Neil Rubin of The Baltimore Jewish Times presents the idea that “comedians [are] our new rabbis, teaching Jewish values in a different, less obvious way to Jew and gentile alike.” Rabbi Waldoks of The Jewish News comments that “like the Jewishness of many people today, Stewart’s Jewishness is not expressed in the synagogue or ritually but in this new place, which is the public square.” Maybe it is not found in the synagogue or ritually, but it is certainly found in the studio of The Daily Show.

The Daily Show itself put together hilarious compilations of many of his Jewish moments, two of which are linked here and here.

One thing that these references have in common is that they are all not shallow jabs. Rather, they contain a deep amount of informed Jewish knowledge – Yiddish vocabulary, stereotypes, customs, holidays, food and biblical stories. However, despite Stewart’s “clear desire to never let the audience forget who he is by bringing his Jewishness up again and again,” his thorough Jewish identity largely does not carry over into his life off-screen.

Neil Rubin notes the irony of the popularity of the Jewish references in The Daily Show’s comedy when “American Jewish life is said to be in trouble, as reflected in shrinking affiliation rates at countless synagogues, schools, and other operations.” Ironically, Stewart himself is indicative of some of these secularizing changes in Jewish life. For example, Stewart married Tracey McShane in 2000, and the pair have two children. In an interview on the David Letterman Show in 2012, Stewart joked, “My wife is Catholic, I’m Jewish, it’s very interesting: we’re raising the children to be sad.” Stewart’s interfaith marriage follows the trend of assimilated American Jews intermarrying and distancing themselves from the Jewish custom of marrying other Jews. Ironically, in a 2009 interview with The Jewish News in which Rob Kutner discusses his own Jewish observance, he remarked that “it was almost always the gentile writers” who wrote the Jewish jokes.

At the heart of The Daily Show, however, is not Judaism, but politics and activism. Stewart’s activism has also shown through in the context of the September 11 attacks in downtown Manhattan. Soon after the attacks, he joined forces with the First Responders and rallied with them to protest Congress to get lifetime healthcare coverage for illnesses caused by the toxic air from that day; initially, they were only given five years of healthcare coverage. Fast forward to early December 2015, when Stewart went on various talk shows, including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, to urge viewers to reach out to their congressmen to increase funding for the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, which would provide this healthcare for 75 more years. In a joyous conclusion, the act passed through Congress on December 18th, 2015, in no small part due to Stewart’s advocacy. Of course, Stewart’s activism does not need to have Jewish roots in order to be considered honorable. However, there is no harm in deeming that his Jewish upbringing contributes to his acts of kindness.

Stewart decided to try his hand at being a director in 2014 with his debut film, Rosewater. The movie is based on Iranian journalist Maziar Bahari’s memoir, Then They Came for Me: A Family’s Story of Love, Captivity, and Surivival. Interestingly, Bahari grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in Tehran. Bahari was arrested by the Iranian government in 2009 under pretenses that he was a spy. Stewart has a personal connection to the story because a segment from when the journalist appeared on The Daily Show as a fake spy was used as accusatory evidence in Bahari’s interrogation. However, in an interview with New York Magazine, Stewart dismissed this motive for directing the movie, saying, “Listen, Jews do a lot of things out of guilt. Generally it has to do with visiting people, not making movies.” Rather, he lists the “universal aspect of it – the absurdity of totalitarian regimes” as his primary motive for telling this story.

Due to the story’s being about the Middle East, there has been much discussion of Stewart’s Jewish identity in coverage of the movie. Various reviews of the movie mention Stewart’s “Leibowitz” roots, presumably to draw attention to the potential ethnic bias of his movie. However, Stewart does not appreciate this reducing of his artistic abilities to questions about his heritage, commenting, “As soon as they go to, ‘Your real name is Leibowitz,’ that’s when I change the channel.” Due to his star status and Jewish identity, Stewart’s intent to create a movie took on a greater meaning and was perceived as a political statement.

Stewart’s identity as it relates to Judaism is a key example of Jewish assimilation and the overall erasure of religious identity while maintaining the cultural components of Jewish observance. Additionally, Jon Stewart is in many ways a representative of the Jewish faith for his viewers and fans, as his cultural Jewishness is a major lens through which Americans are presented with Judaism. Ambassadors as generally well-liked as Stewart are hard to come by: Stewart is “smart but not arrogant, extremely funny but not mean - a valedictorian, most popular, best-looking and class clown all wrapped into one.” I think Jews could do much worse than with a spokesperson like Jon Stewart to carry the torch of Judaism in the 21st century.