There is a saying in story-telling: “Real life writes the plot.” This phrase results from a writer’s desire to incorporate the context of current events in the story. The newest installment in the Bourne series is a case example of how not to do so.

“Jason Bourne” (2016) is an action thriller directed by Paul Greengrass, a continuation on the storyline concluded in “The Bourne Ultimatum” (2007). The titular character has out-smarted a ruthless CIA and its endless gauntlet of assassins over three films as he attempts to regain his memory and his identity. But now, the fourth film mixes up the formula by tossing around Jason Bourne within a post-Snowden world, complete with a side-plot surrounding cyber-surveillance and privacy.

I say side-plot-- that's because almost nothing regarding the issue of government-enabled backdoors in a social media platform actually relates to our protagonist, Jason Bourne. Instead, the main plot deals with Bourne’s struggle to understand the connection between his father and the assassination program he was recruited into before he lost his memories and became the hunted in the CIA’s most dangerous game. They’re two entirely separate plots that conflict with each other in themes and direction.

When the focus is on Bourne, the pacing is swift, the atmosphere is constantly tense, and a mystery plays out piece by piece. Those scenes are reminiscent of the thrilling action sequences of the original trilogy. However, at some points, the movie jumps to this bland media mogul, Kalloor, who fights for the individual’s privacy against a morally bankrupt CIA director, Dewey, who desires to access people’s private information and the movie grinds to a screeching halt. The viewer is invested in Bourne’s struggle to regain his past and define himself; the viewer is bored by the mogul’s struggle to fight for privacy and eat up screen time.

The problem with the film’s attempt to incorporate real-life social context is the controversy of individual privacy versus national security spawned from Edward Snowden’s leaks. It is solely used as a plot point, rather than an integral quality of the Bourne-centered story. As A.O. Scott of the New York Times eloquently explained: “Terrorism and surveillance are treated both as facts of life and as vaporous abstractions. When Dewey talks about protecting the homeland, or Kalloor speaks of the importance of protecting consumer data, the words carry no real conviction, on the part of either the characters or the filmmakers.”

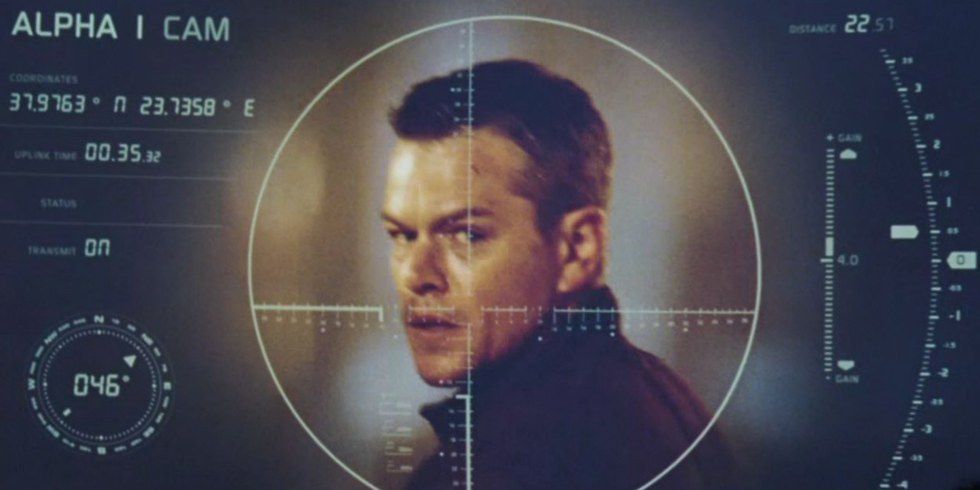

The only noticeable impact the context has on that main plot is the use of modern surveillance to hunt Bourne—social media feeds, street cameras, remotely hacked cellphones. These methods appear outdated, when one considers that the CIA in “the Bourne Ultimatum” were able to target a British reporter, just because he uttered the name of an assassination program in a phone conversation. One may get the impression that the writers of “Jason Bourne” ham-fistedly incorporated cyber-surveillance into Bourne’s story just to loosely connect real-life issues with the main plot.

In essence, “Jason Bourne” is a film that fails to effectively mix its story with the social context it presents. Whenever the issue of privacy versus security pops up, it’s poorly integrated with the thriller dynamic of the Bourne series, resulting in stale scenes, half-hearted commentary on the subject, and irreversible damage to the pacing and feel of the film. If real life has to be incorporated into the plot, the writer should be sure to perfectly mesh the story and the context.

The original Bourne trilogy (the movies, not the books) has mostly been able to accomplish this task well in regards to the issue of national security following 9/11. The films constantly weigh ethics versus duty by showcasing the government’s willingness to spy on people, eliminate suspects, and ultimately avoid responsibility for the repercussions. Bourne’s own quest to understand his role in these illicit activities is built upon this theme. He represents the remnants of principles and humanity that the CIA abandoned in its patriotic crusade for national security.

Although these films have always been crazy summer blockbusters, they do not treat their social context as fluff for their plots; they let the context write their story.