I “met” Vivian Kellogg while walking around the Ella Sharp Museum on a Saturday, working my way through the gallery. Being that this was my second volunteer experience, I wanted to get familiar with the galleries.

The Never Enough Time gallery is a permanent exhibit about clocks. Cuckoo clocks, sculpted clocks, clocks on canes, Grandfather clocks, wall clocks, clock gears, astronomical clocks, a model clock repair shop, a couple of watches, clocks that tell the year, clocks that cycle the moon, clocks that just tell time.

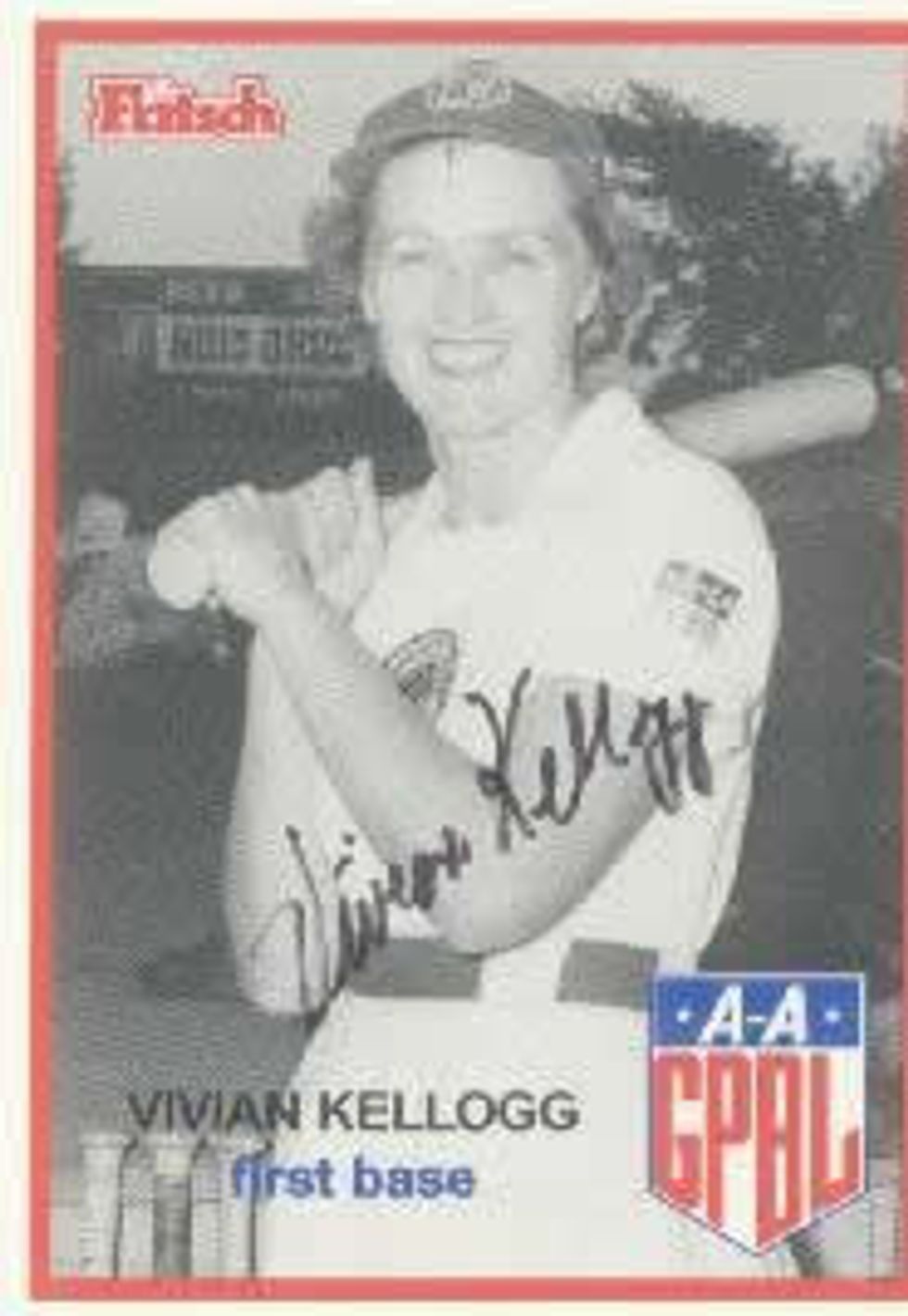

I turned to leave the clocks, and then I saw her picture in a glass display case. Vivian, in her 70s, was clinging to a sign for Concord, Michigan, smiling. The sign read “Welcome to Concord. Home of AAGPBL player, Vivian Kellogg.” Her maroon varsity jacket for the Fort Wayne Daisies was underneath that picture, so was her baseball card, her league membership card, and a baseball signed by her.

I turned to my friend, Kasee. “I didn’t know there were Michigan players who played in the Professional Girls’ League.”

“Have you seen A League of Their Own?” she asked.

“It’s one of my favs,” I answered.

I looked at Vivian’s baseball card. Memorized that face. The smile, pin curls, red lipstick, the baseball bat. I had to get to know this lady.

On the surface, the All-American League looks like a stunt to keep an already rich man even richer. At the height of World War Two, every sector of industry was facing employee shortages due to the war; manpower was no longer as available, from San Francisco to New York City, from the factories and farms to the movie studios and the great stadiums. Most of the country began to turn to womanpower. This was especially problematic for men like Phillip Wrigley, chewing gum tycoon and Chicago Cubs owner, who needed to keep making money. With less ball players than ever, he backed a new novelty idea: dress girls up in short dresses, have them play baseball, draw in the crowds, reap the rewards.

But for Marilyn Jenkins, a former player, there was so much more to offer. “If we broke barriers with all that, then I’m happy for that. When I think back to ’45, things were so rationed, people didn’t have cars. We just put a lot of joy into a lot of people’s lives.”

Michigan was home to four teams: The Grand Rapids Chicks, the Muskegon Lassies, later the Kalamazoo Lassies, and The Battle Creek Belles.

The Chicks played at South High School in Grand Rapids. They converted the old football field into a baseball diamond for the girls. Gerald R. Ford began his football career at that field, before they turned it into the Chick’s home field. When you Google “South High School Grand Rapids,” nothing shows up but the word “was.” South High was where Ford went to high school. It was the home of the Grand Rapids South Trojans. It was opened in 1915. It was called the crown jewel of the Grand Rapids Public School system. It graduated its last class in 1968.

The building was abandoned for 16 years. It’s now called The Gerald R. Ford Job Corps, an educational and career tech training facility. There one can learn carpentry, culinary arts, office administration, and facilities maintenance, among other jobs.

There is no sign of the Grand Rapids Chicks.

At least the Kalamazoo Lassie’s field is still used for sports, , albeit Kalamazoo’s D-league soccer team, the Kalamazoo Outrage. When the Lassies were moved to Muskegon, they played at Marsh Field, which is still used for recreational baseball. The website for Marsh Field tells the history of the field, the semi-pro Muskegon Reds, and the Negro league team, the Muskegon Clippers. But the Lassies have been erased from the field’s history.

64 Michigan women played in AAGPBL—from Beatrice Allard to Marie Ziegler. Each of their stories, no matter how brief, were catalogued in 1998 when the AAGPBL website was first launched. Girls like Sophie Kurys, a Flint native and Racine Belle, who had played ball her whole life in dirt yards; when she decided to join the league, her dad refused to let her go, so her mom bought her ticket to Chicago for training. If she had been in A League of Their Own, she would have played with Kit Keller, one of the film’s protagonists, but she would have been better than Kit Keller. She was named player of the year in 1946.

For forty years, the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League was just the faded dust memories of those who went to the games and played the games. It wasn’t until the movie came out that anyone wanted to know these stories. It helped that three of the biggest movie stars of the early 90s—Geena Davis, Tom Hanks, and Madonna— were in the movie.

I did come to know Vivian, through research, a conversation with Marilyn Jenkins, and a conversation with Vivian’s nephew.

Vivian Kellogg died in 2013. She was a dental receptionist who loved sports. In fact, in 1992, she was inducted into the Jackson Bowling Hall of Fame. She was one of seven children, the last of the Kelloggs to survive. Her brother, Clarence, was a Jackson industrialist, founding Kellogg Crankshaft, “a global engineering company, specializing in design, development, and manufacturing of crankshafts for Automotive, Engineering Machineries and Oil/Gas Industries.” She never married.

“Kelly,” as she was known on the field, was a right-handed first baseman. She played one year for the Minneapolis Millerettes; then the team folded. She spent the remainder of her career playing for the Fort Wayne Daisies. 8 Career home runs. Recruited right out of high school. She chose to play ball because she would earn more playing ball than she would at Bell Telephone. She retired early because of a knee injury. A signed Vivian Kellogg baseball card goes for 88 dollars on Ebay. In her picture, she flashes a brilliant smile, pin curled hair, red lipstick, crisp white uniform, and bat in hand.

Probably for most of her life, she lived an uneventful, conventional existence. I imagine that until 1992, her neighbors knew her as the graying older lady named Vivian Kellogg. She was born in Jackson County and she died in Jackson County. I can imagine the shock on their faces when they realized that she had been a professional baseball player.

There isn’t any movie about Vivian Kellogg’s life. There aren’t even “Save the AAGPBL campaigns” as there have been for many pieces of WWII history. If you Google the name of any player in the AAGPBL, you will read the same phrase over and over again, “She played in the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball league, which inspire the movie A League of Their Own.” In other words, no one player ever made history on their own. The individuals are always a mystery.

There’s an idea that history is the collective deeds of great men. But I have come to believe that the people who lived it are the backbone of history, even when they become obscured. But we, in the present, have an obligation to honor those from the past. So this is for Vivian Kellogg, Jackson county’s baseball heroine.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion