"It's not your fault."

For people who have gone through and witnessed trauma, it's something you know to be true. Who doesn't? Who thinks a young kid or even teenager could stand up to a physically overpower an abusive father? Logically, everybody knows that a wife or girlfriend being hit by her partner is not culpable. Anyone who has witnessed and experienced trauma knows that it's not their fault.

But that is logic. That is rationally knowingthe reality of the situation, but it is a completely different ballpark and much simpler journey than truly acceptingthat it's not their fault. With knowing, the person still has their guard up. Knowing is an appearance of toughness and grit, of pretending that whatever trauma someone undergoes no longer bothers them. With knowing, it's simply a matter of being aware of a situation, and that is its limit.

Accepting, on the other hand, is an emotional state of mind that allows vulnerability and doesn't take a band-aid solution for an answer. Accepting is realizing that trauma still affects you, ending your denial, and putting yourself on a path to change things. Accepting is something that is never truly over, that takes a lifetime to achieve.

For example, an alcoholic can know that they have a problem, but not have want to do anything about it. But a recovering alcoholic can accept that their current state of affairs is unsustainable, and realize that things need to change.

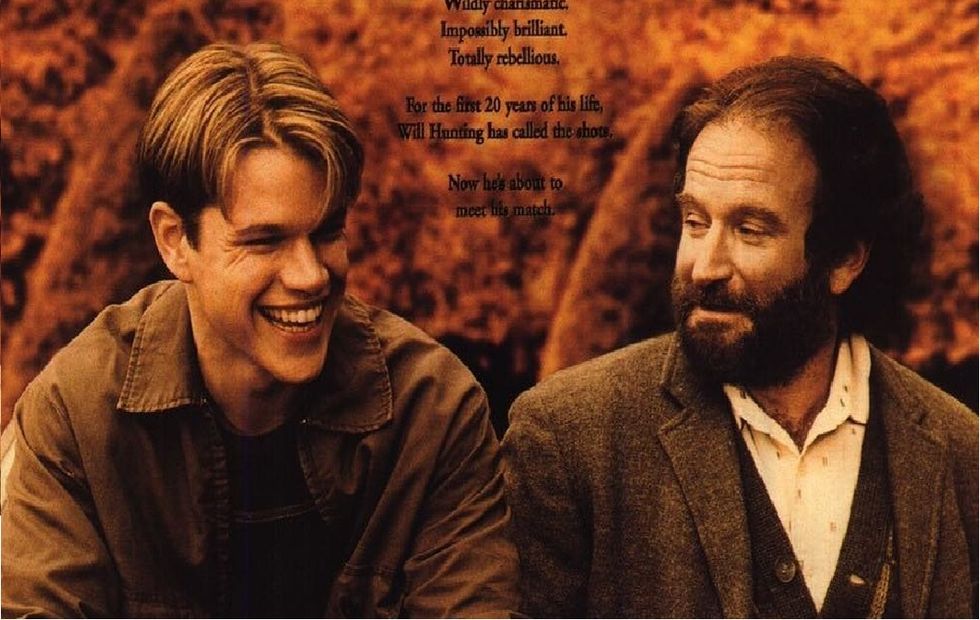

It's a confusion distinction and certainly not a black and white series of concepts. But in reality, the best depiction of this is the famous "It's Not Your Fault" scene from Robin Williams and Matt Damon's "Good Will Hunting."

Will has been meeting with his counselor, Sean, who finally got him to open up about his relationship and his childhood of abuse. In this scene, Will asks Sean if he's ever "experienced that," in reference to whether Sean himself has personally experienced abuse and been beaten by his parents, to which he replies in the affirmative.

It's next when Sean repeatedly tells Will that "it's not your fault." About six or seven times, the process repeats, while Will says "I know" each time. Eventually, he pushes back and says "don't fuck with me, Sean." But Sean repeats the phrase until Will breaks and starts sobbing, finally being to accept that it's not his fault.

You have to watch the scene to truly understand and emotionally connect to it, so please take a couple minutes to, if you haven't.

As you can see, knowing is something that Will experienced immediately after being beaten by his foster parents, something he was aware of immediately. But accepting is what Will is finally able to do in this scene with Sean when he cries, one of the few people he truly has been able to connect with and trust.

People can't accept easily. It's not something they can ever master in their lives, because it's healing from events and processes in life that will leave them forever traumatized. All they can do is make progress, and maybe use their experiences to guide them through their lives, so each person has to find their own unique path.

I recently opened up for the first time about growing up around a similar situation as Will. I was at peace after what I'd done, but that doesn't mean it's any more easy or anxiety-provoking than the first time I talked about it. For a long time, it's going to be like that. Accepting is never something that can happen in the span of a day, a month, or even a year. It is what it is, and now I have to roll with it.

But I see this happening with the people around me. It's one person or a few people, in a stage of accepting, that will bring others into a stage of vulnerability and catalyze other people to do the same. On one hand, no one wants to see one of their friends be vulnerable on their own. I've witnessed it happen before, and you feel guilty, because it could very well be you on that stage, and you'd want someone else to stand and suffer beside you. This shared vulnerability may scare people beyond bounds, but ultimately has a positive and profound effect on relationships, on communities.

Accepting, on this note, is far more rewarding than knowing could ever be. Knowing is the act of ending the conversation and being in denial and rebellion of God's path for you. I'm certainly not the most religious person, but I see accepting as the act of following that path and sticking with it, despite the relapses and obstacles in doing so, and letting yourself be alive.