September 15, 1963 – Birmingham, Alabama.

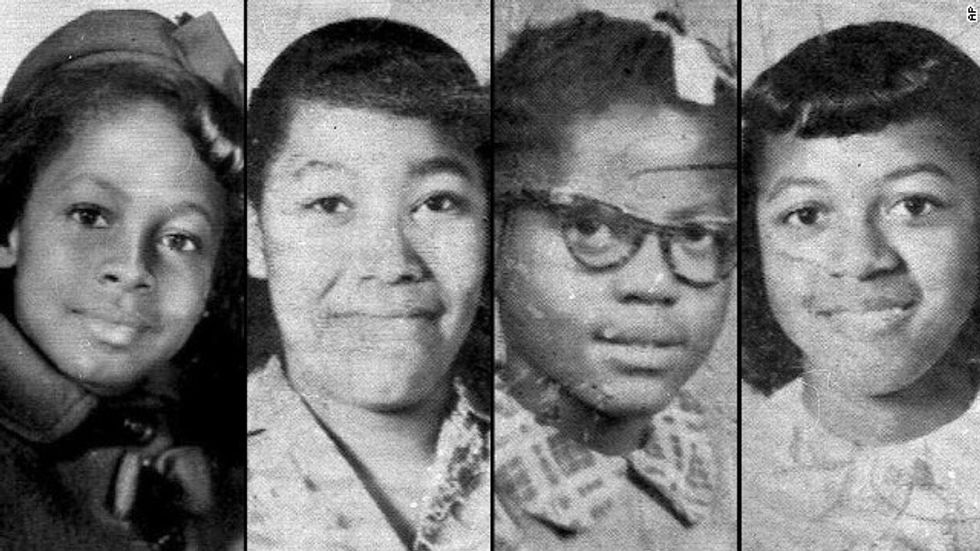

Families woke up and got ready for Sunday school just like every other Sunday morning. Mother’s kissed their daughters, expecting to see them at lunchtime. Robert E. Chambliss had other plans. At 10:22 A.M., he abruptly ended the lives of four young girls, between the ages of 12 and 14. He devastated 16th Street Baptist Church, families, Birmingham, Al. and the world. “The bomb heard ‘round the world” had detonated, creating a war between protesters and the justice system. Because of the national attention the city received following the events of September 15th, Birmingham earned the nickname "Bombingham."

September 15, 2015 – Birmingham, Alabama.

My professor tells us that today was the 52nd anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Honestly, it sounds depressing. I could be reading my book that I have been dying to finish or do some homework. I could even go to sleep early. But at the last minute, I decide to go with two of my friends. I have heard about this church my whole life, living in Alabama, but I have never actually been. So I figure that it would be a cool experience to say that I went there and for such a historic reason.

Two friends and I turn on to 6th Avenue North at the command of the GPS. I see the Civil Rights District for the first time since about the fifth grade. We are discussing what we expect from this service. All of our thoughts are relatively similar; sad, interesting, historical, and reflective. But one I can’t shake – or admit that I’m feeling – is awkward. This ceremony is a tribute to innocent lives damaged and lost at the hands of hatred driven by racism. It was a hate crime, conducted by the Ku Klux Klan, carried out by a white man, on a predominantly black church. This screams confrontation.

We walk up the stairs of the Civil Rights Institute and into a long room, divided into three sections of fold-up chairs and a podium, front and center. The left section is filled with Miles College Choir members, dressed in gold robes. The middle section is mostly older men and women, who lived through some or all of the events in the 50’s and 60’s. And then there was the right side – full of children who were participating in the ceremony, their parents, a camera man, and the only three white people in the room, two of them being my friend and I.

It isn’t like anybody is looking at me or making me uncomfortable. Everyone is extremely nice and excited to welcome us into the room. The energy was strangely high for this sort of thing.

The choir is angelic. Their harmonies and solid tenor section make for a sound nothing short of goose-bump worthy. They open the service, followed by a prayer, and an introduction by the newly appointed president of the Civil Rights Institute. Then, five little girls make their way to the front.

One sits in a chair playing with a doll while and older girl is fixing her hair. They start a skit in which the words are a poem from the perspective of one of the victims and her mother. It is heart-wrenching from the beginning. The joy between the two characters is a light-hearted way to start, but to know what’s coming is pretty close to dread. I’ve always loved acting because hearing and reading about history is one thing, but to see it in front of you – an attempt at real-time – is a really incredible thing. At this point, people are crying. It is hard not to feel the pain, fear, and the confusion of the characters.

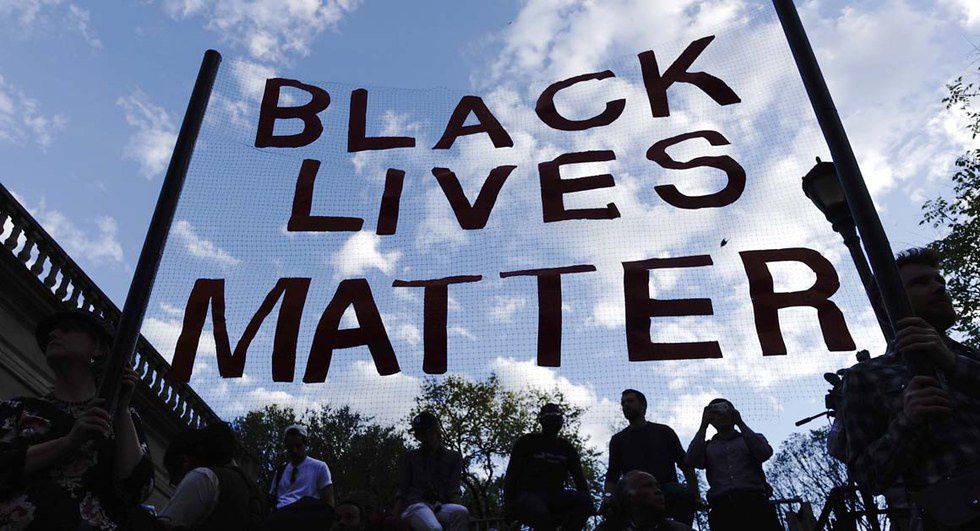

The crowd is quieter now, and the air a little heavier. Some members of the interfaith community prayed and we listened to more music. I was loving all of this – the raw emotions, the facts, hearing from people who really lived through this. It was incredible. There was so much reverence and love in the room. These are people who truly care and want the world to change for the better. The choir finished their song and the next speaker was the leader of the Black Lives Matter Birmingham.

He wore a white suit and a black t-shirt reading “#blacklivesmatter” seen between the folds of his jacket. His black hat with the white American flag sat low, nearly covering his eyes. He wasted no time once he got to the microphone.

“A moment of silence… Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, Carol Denise Mcnair. Trayvon Martin. Eric Garner. Michael Brown. Sandra Bland. Freddie Gray. Walter Scott.”

Have all of these people really been killed in the last year? Even worse, have they really been killed because they're black?

His voice has a harsh edge and is getting louder with every name. But then he stops, and speaks hauntingly low.

“52 years. You all are here remembering what happened 52 years ago. You can sing your songs about how we’ve made progress, but just because it’s better than it was doesn’t mean that it’s good. We have been fighting for our lives for 52 - no. Let’s go back. Five hundred years. We have been property, we have been devalued, and we have been murdered. Five hundred years later, I have to wear a t-shirt,” he pulls open his jacket, “to prove that MY LIFE MATTERS.”

This isn't about 16th Street anymore.

He was now so loud in the microphone that the bass in his voice could be felt in my chest. I was almost afraid to breathe. Every time he looked toward me, he looked at my eyes and I averted them quickly. I felt embarrassed.

I was not ashamed of my actions, but rather my lack thereof. I see it all of the time – whether it be around me or on T.V. – and I don’t say anything because “I’d rather just stay out of it.” I’m afraid of the confrontation that follows and for the first time in a long time, I feel like that’s wrong. But why?

He says something about fearing for life and being guilty until proven innocent and it silences my thoughts. Suddenly it makes sense. Here I am in a room – surrounded by people unlike me – listening to a man full of such anger towards people like me. Although I (personally) had not done what he was speaking of, I felt sick. This went past awkward. This was debilitating. Because there are people who feel like this all of the time.

There are people who fear for their lives, are the recipients of unjustified anger, violence, loss, and they feel all of the time like I hated feeling for 10 minutes. This is transformative. I put myself in a position of learning, of understanding, of truly – for the first time – feeling what it might be like to be a minority, though on a very small scale, and I get a glimpse of what it means to be a minority in the United States in 2015.

In a world of violence, death, persecution, and lack of equality, we are still talking about our unity, tolerance, and our beautiful “melting-pot” of a country. I believe that America is every bit of that; but we’re only as good as our least tolerant citizen. So, with that, I ask:

Why, if we’re trying to create this sense of togetherness, do we insist on trying to separate by the color of our skin? More than that, why are we killing over it? Living in unity is a collective effort. We need each other.

"The idea that some lives matter less than others is the root of all that is wrong with the world."

-Paul Farmer

Miles College Choir sang a song (by Hezekiah Walker) that puts it perfectly:

“I pray for you. You pray for me.

I love you. I need you to survive.

I won’t harm you with words from my mouth.

I need you to survive.”

16th Street Baptist Church is a beautiful example of change. What was once torn apart by the hands of hate, was more quickly put together by hearts of love. Spiritual and emotional wounds were healed by community and togetherness.

And on a larger scale, once famous for violent water hoses and German Shepherds, Birmingham is now called “The Magic City” for fast growth in population and industry and diversity.

Restoration can be a reality but it can’t be in the interest of social or political issues, but rather the value and sanctity of human life.

Knowledge will change you, but what you do with that knowledge will change the world.