"Your brain does not process information and it is not a computer." A friend sent this essay to me, now titled “The Empty Brain," and asked for my commentary. It is an essay written by Dr. Robert Epstein, a distinguished scholar with a PhD in psychology from Harvard University, which I, a mere undergraduate majoring in cognitive science and behavioral biology, will attempt to respond to.

Epstein's essay attacks the computational theory of mind -- the idea that the brain is an information processor -- which has become increasingly prevalent in the cognitive sciences. He states that this idea is nothing more than a metaphor and does not serve to explain how the brain works. His argument hinges on a few key points: that the brain does not create and store representations, that the brain does not compute using algorithms and that individual brains are unique and constantly changing, therefore making them unlike computers. However, his essay demonstrates a misunderstanding of the ideas he argues so vehemently against.

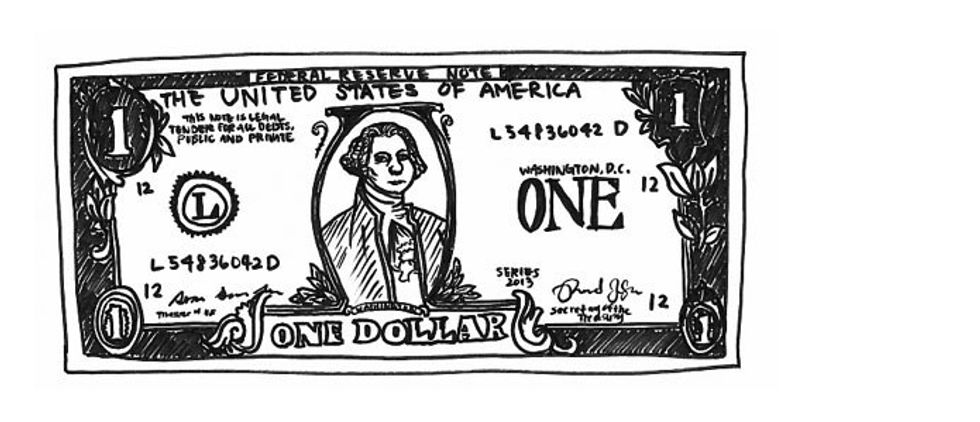

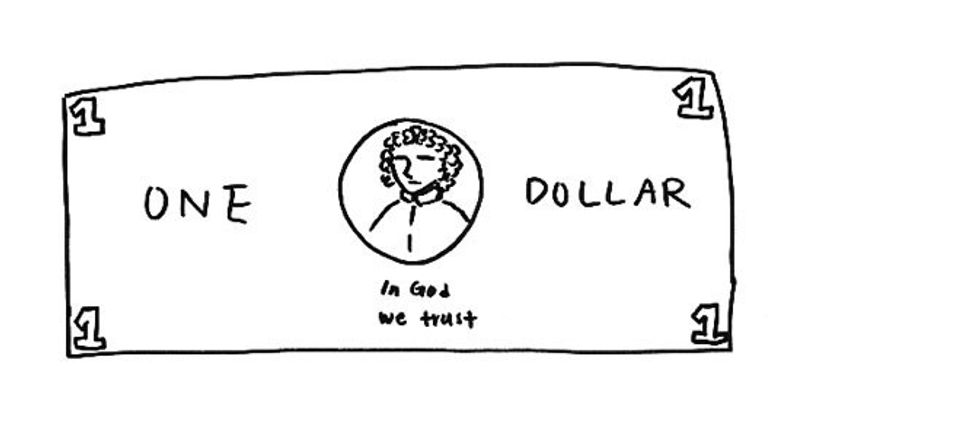

I will begin with mental representation. Per the "information processor metaphor," the brain perceives stimuli and processes them to create mental representations which it can then store and retrieve. Epstein provides an example of why the brain does not process, store, and retrieve through a memory exercise. He asked a student to draw a dollar bill from memory, and then asked the student to copy a dollar bill. A comparison of the two drawings yields predictable results.

Epstein believes that the lack of detail in the first drawing is evidence that an image of a dollar bill has not been stored in the brain. He states that his student's brain has been changed by the previous sight of a dollar bill, and that they must re-experience seeing a dollar bill in order to draw it. Yet how is this different from storing and retrieving a memory? If anything, it proves that we store representations of objects. The dollar bill itself is not stored in the brain. A useful model, a representation, of a dollar bill was stored. Research has shown that visual perception and memory are modulated by attention, and interestingly, the aspects of the dollar bill which were remembered correctly are the ones which we attend to the most: the numbers in the corners, whose location we must pay attention to in everyday life, and the face in the middle, something which we are naturally attuned to noticing (we even have a specific brain region - aptly named the fusiform face area - dedicated to detecting faces!).

Mental representations have concrete, scientific evidence supporting their existence. For example, let's imagine you are looking at a black square. There are specific neurons in your primary visual cortex which are attuned to specific orientations of lines in specific areas of the visual field. Epstein states that it is "preposterous" to say that memories and representations are stored in individual cells, asking "how and where is the memory stored in the cell?" That question belies his misunderstanding. The representation is not within the cell -- the representation is the cell, its activity (or lack thereof) in response to stimuli and its synaptic connections with other neurons. Within your brain, there is no smaller array of four black lines which is hidden in the cytoplasm of a neuron. There are only combinations of firing neurons, which together comprise a representation of an external stimulus.

Epstein also states that while computers run entirely on algorithms, humans do not. However, his argument seems to be cemented in the belief that computations must be conscious. The "algorithms" that our brains follow are innate and genetically programmed results of evolution. A sunflower cannot consciously compute, yet it grows in spirals which follow the Fibonacci sequence. A female ant will, on average, help another female ant in its colony three times more often than another male ant; however, any given female ant does not think to itself "I helped Michael once in the morning, and therefore I must help Nora three times in the afternoon."

Female ants within a colony are, on average, three times more related to each other than female and male ants; therefore, through evolution, they have become genetically programmed to increase their indirect fitness by helping those who are most related to them. All other ants with programs that do not maximize fitness have been weeded out, and we are left with three-to-one female to male sex ratios in modern day ant colonies.

The same can be said of humans. Epstein provides an example of a baseball player catching a fly ball to prove his point. He states that the IP metaphor would require the player to calculate the trajectories and forces of the ball as it approaches. However, what if the player was simply moving in the appropriate direction until the ball was caught? According to Epstein, this second alternative is "completely free of computations, representations, and algorithms." Sure, it is devoid of conscious computations. It would be absurd to assume that we must consciously compute the trajectory of an incoming ball in order to catch it.

However, we can map model the neuronal firings between the visual cortex and the premotor cortex. We can create neural nets which incorporate feedback from the environment into their calculations order to catch an incoming ball. If these models are constructed from analogous building blocks (perceptrons in neural nets, and neurons in the brain), and yield the same results, why can we not say that we have been programmed to subconsciously compute?

Epstein states that we cannot create computational models of brains for two reasons: One, every brain is uniquely shaped by experience, and two, brains are constantly changing, and a model of a brain at any given point of time would be rendered useless once the brain changed. He discusses how no two people will tell the same story the same way, therefore proving that each brain is different and that we cannot create a single model which explains human behavior.

However, Epstein appears to overestimate the number of ways in which the brain can change. Brain regions, and more specifically, neurons, can either increase or decrease in size and number of synaptic connections in response to environmental stimuli. Since information is stored not in the neurons themselves, but in the connections between neurons, increasing the number of connections improves the amount of information which is stored. The differences between the two stories are not due to different underlying brain structures, but different responses to the same stimulus. While the specificities of neuronal growth differ between individuals, the mechanisms are the same.

Epstein also demonstrates a lack of faith in the robustness of mathematical models for the brain and their ability to mutate and learn. If we were to create a perfect AI which mimicked every aspect of the human brain, then it too would constantly change in ways which are unique to it. Although brains are individually molded by experience, they all follow the same blueprint. Every brain has a frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortex.

We can model the functions of these brain regions, and we can model how they are affected by experience. If we were to take a snapshot of the brain, we would have both a record of the state of each neuron at that time, as well as a record of each neurons ability to change. We would see the neurons which stimulate the growth of synaptic connections in other neurons, as well as which neurons would be most likely to grow in response to specific stimuli.

Epstein also provides a historical commentary on the development of our analogies for the brain by comparing them with complex technologies which arose at the time. The invention of hydraulics in the third century BCE led to a hydraulic model for the mind, in which the mental state was controlled by the four humors. The Industrial Revolution spurred the idea of the brain as an automaton. And today, in the 21st century, in this era of technology, we see the brain as a computer. Epstein argues that our current analogy is one which will either be "replaced by another metaphor, or in the end, replaced by actual knowledge."

Epstein states that the IP metaphor confines the ways in which we think about the brain; however, I merely see a definition of science which suppresses scientific endeavors. We oftentimes like to think of science as a quest for "knowledge" or "truth" -- we want to find the answers, and we do so through the scientific method. But what if we define science not as the quest for knowledge, but as the quest for understanding?

If religion is a way in which we explain the world and create order within it, then science is nothing but another religion. Science is bound by its methods: the collection of data through observation and reproducibility of results. It follows methodological reductionism, in that the sciences build upon each other -- biology reduces to chemistry, chemistry reduces to physics, physics reduces to math. The modern scientist will scoff at Freudian psychology, because the Id, Ego, and Superego are not observable, reducible phenomena. However, the modern scientist does not belittle the Rutherfordic atomic model. Its inaccuracy is forgiven because it was developed through experimentation and subsequent observation; namely, the scientific method. Rutherford observed reproducible results which expanded our understanding of the atom and have been used to build subsequent models.

There is scientific evidence supporting the idea that the brain is an information processor. We have found neural correlates of the visuospatial scratchpad in working memory and action representation in the motor system. If Epstein fears that we will one day find the IP metaphor to be "silly," I must ask him to rest assured knowing that we will not. It is a model of the brain which has led to robust and reducible theories for how the mind works. The subsequent models which replace it will incorporate the discoveries which are being made today.

We must learn to overcome the uneasiness associated with thinking of the brain as an organ. If we are to create a better scientific understanding of ourselves, we must abandon the idea that the mind is not bound by physical laws. And if our most scientific understanding the mind is truly limited by the complexity of current, man-made technologies, then we must think of the brain as an information processor. What other option do we have?