Between the wage gap, politicians pushing to ban abortion, high rates of sexual assault, and underrepresentation of women in politics, the United States suffers from an abundance of serious gender inequality issues. To claim that men who insist on paying for dates or give up their subway seats to women undermine women’s status in society to the same extent as unequal pay and laws restricting women’s rights seems absurd. In their 1996 essay, “The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory,” professors Peter Glick and Susan Fisk make this claim, by defining and explaining the downfalls of a friendly brand of sexism they call “benevolent sexism.” By disguising itself as innocent friendly remarks and gestures, benevolent sexism often goes unnoticed by those on the receiving end and by those who perpetrate it. However, it deeply affects the way both women and men are viewed in society, despite the good intentions of people who compliment a female scientist on her looks rather than her work, or praise a father for “babysitting” his kids without his wife to help him.

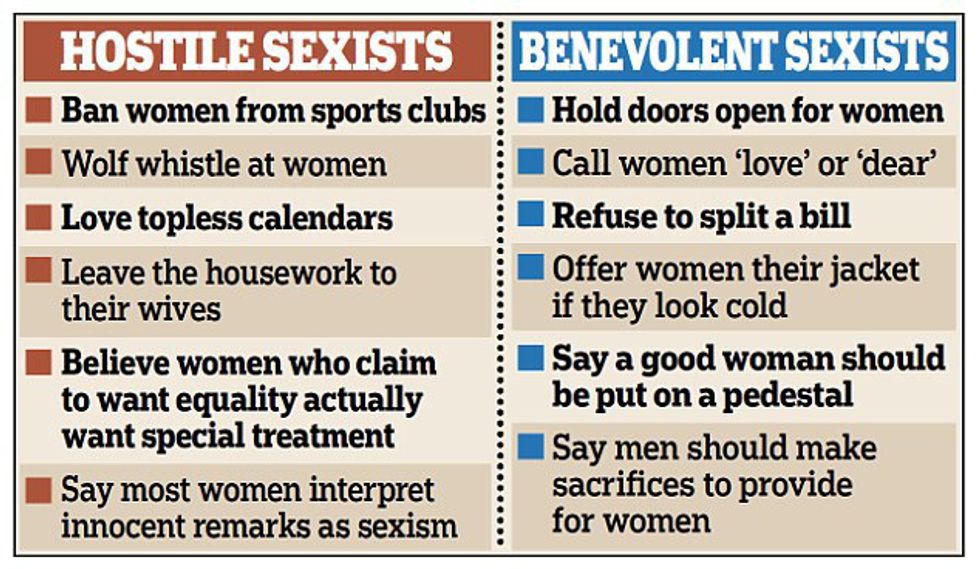

In a recent study published in the academic journal "Sex Roles," researchers from Northeastern University asked 27 pairs (of one male and one female) to play a trivia game together and then engage in conversation. They then tested the males using the Ambivalent Sexism test, in which they rated their agreement with statements that demonstrated both hostile and benevolent sexism, such as “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess,” “Women exaggerate problems they have at work,” and “When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against.” When comparing the men’s behavior when interacting with women to their answers on the test, the researchers found that the higher men scored for benevolent sexism, the more likely they were to be patient and friendly towards the women. According to Jim Goh, a psychologist at Northeastern, this proves that sexism can seem “kind of appealing as a sort of chivalry,” while benevolent sexism contributes to inequality because it teaches men not to “expect women to achieve high goals” independently.

Benevolent sexism’s ambiguous nature makes it hard to identify — it can come in the form of a well-intentioned comment expressing surprise that a woman became successful in a “man’s job,” or a relationship in which the man always takes the responsibility of driving or fixing things around the house. Although this polite form of sexism presents itself as good manners and respect for women, it perpetuates the harmful stereotypes of man as sole provider and woman as sole caretaker that society has failed to overcome since the 1800s.

In comments sections of articles discussing benevolent sexism, I found that many people made the same statement: that people who get angry at benevolent sexism “are just overreacting,” or simply can’t tell the difference between sexism and chivalry. However, those who think of benevolent sexism as harmless fail to see the very real ways it affects gender roles. After writing about benevolent sexism, Glick and Fiske asked 15,000 men and women across nineteen different countries to rate their agreement with both benevolent and hostile sexist claims. They made two shocking discoveries: that people who displayed benevolent sexism were more likely to display hostile sexism, and more importantly, that men’s levels of benevolent sexism reflected the gender inequality of their respective countries. In countries where men showed more benevolent sexism, men made more money, had higher literacy rates, and had a larger role in politics than women did. In a 2013 study, professors Julia Becker and Stephen Wright asked women to read sexist statements, and found that women exposed to benevolent sexism were less willing to take a stand against sexism by participating in rallies or signing petitions.

Benevolent sexism also “tolerates and likely reinforces women (but not men) to act more anxious and less confident" (e.g. concerning bugs or driving.) Society’s belief that men should help women by killing insects or fixing things for them maintains the female stereotype of being fearful and naïve, rather than empowering women to protect themselves and do things independently. “Friendly” sexism harms men as well as women, as it reinforces the idea that women are more caring and better at parenting than men are. Very rarely are fathers allowed to take time off from work when their new child is born, and a majority of states more often grant custody to the mother “in the best interest of the children” when parents divorce. Benevolent sexism holds more prevalence in society than many realize, keeping traditional gender roles in place.

In a poll that asked if good manners can be sexist, 83 percent of people answered “no.” Many people think that sexism can only come in the form of aggression and hostility towards women. But Northeastern University Professor Judith Hall refers to benevolent sexism as a “wolf in sheep’s clothing.” This name perfectly describes its misleading nature, despite its friendly facade, benevolent sexism will continue to hinder the ongoing process of breaking down gender roles until society can recognize it for what it is: a valid and harmful form of sexism. This is not to say that you should stop holding doors open for women, or get angry when someone offers to pay for your meal; parts of benevolent sexism are engraved into our society as chivalry and politeness. However, it is important to notice and acknowledge how your words and actions, no matter how well-intentioned, could be reinforcing gender stereotypes.

Take the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory here: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/are-you-sexist...