“The Red Studio”(1911) by Henri-Émile-Benoît Matisse reveals his inner head space, his personal battle against the tradition of academic art.

"The Red Studio" (1911) by Henri Matisse, oil on canvas, 71 1/4" x 7'2 1/4" at the Museum of Modern Art

Matisse gives his pictorial workspace an overwhelming muted warm red and pairs it with awkward areas of emptiness. If closely examined, there is a distinctive variety of colors under the rough lines that depict the furniture; the red was painted over a colored canvas rather than outlines painted on top. Matisse shaped his entire painting in a reverse figure-ground relationship, further emphasizing his revolt against academia’s standard realistic and highly constrained perspective. He creates a void like interior space, but he also keeps it welcoming by pairing the strong presence of the red color against bright, often complementary colored, paintings.

After contemplating the vast red space, the eye is drawn to the composition of the objects within the room. The placement of the objects guide the eye in a clockwise direction Also, nothing is scalled accurately; some paintings are the size of the very small sculptures that is also equal to the size of a plate. The arragnment of pieces, perceptive sizing, and incorrect angles of furniture emphasize that this is specifically Matisse’s perspective of how he works. The emptiness of the floor in combination with the color invites the viewer into Matisse’s unique space that is brought to life solely by the objects close to the artist’s heart.

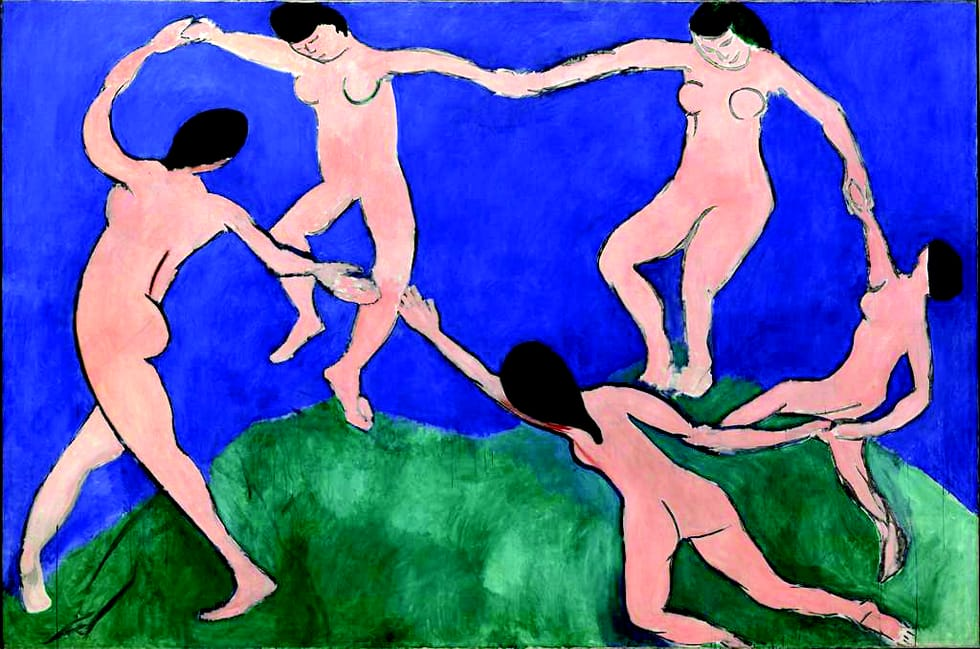

"Dance (I)" 1909 by Henri Matisse, oil on canvas, 8' 6 1/2" x 12' 9 1/2" at The Museum of Modern Art

Matisse considered the impressionists when developing his color theory. For example, Vincent Van Gogh’s “Le Café de Nuit” (1888) includes feverish strokes of vibrant green on the walls, wood, light, and people. By attempting to mimic nature’s unseen “pure” colors, the impressionists accidentally introduced the possibility of personal color choice and context.

From exposure to Japanese prints, Mattise also looked at how color interacts with surface. Japanese ukyio-e wood block prints had vibrating colors unseen previously in the West. They popped and “floated” off of the canvas and tested the viewers' perceptions. Matisse built on the customization of observational art and applied it to an flat but active presentation of subject to develop a style focused on harmony and visual manipulation.

His break down of the Impressionist's color palettes and vibrancy of Japanese art gave Matisse the lead in the Fauvism movement. The Fauves focused on painterly qualities and strong colors over symbolic representation. They rejected the realistic values of tradition to convey messages, and Matisse’s color theory became popular to follow. Color was a means to project the internal mood or deconstruct the accurate structures. They often painted traditional subjects, such as portraits or landscapes, to emphasize their manipulation of color and their emotional response towards nature.

"Reclining Nude, I" (1906-07) by Henri Matisse, bronze, 13 1/2 x 19 3/4 x 11 1/4" at the Museum of Modern Ar

Matisse also experiments with the composition of traditional artists and uses academic techniques in unconventional ways. Rembrandt Van Rijn presents himself peculiarly small and the canvas exponentially large in the “Artist in His Studio” (1628). Rembrant captures the discouraging moments of decision when creating art in a room bare of everything except his art essentials. However, the still emptiness of the room that distorts the artist and the canvas still conform to a very academic one-point perspective and typically contribute to the paintings drama. Matisse creates an illusion of scale through estranged placement of items and also entirely removes any kind of realistic spacial perspective. He presents a concept that the artist makes the art, not the time or place, by having the paintings and objects distort emptiness and create perspective.

He also innovates in composition by practicing sculpture. After being commissioned several times to recreate traditional statues, Matisse discovered the expressive hands on manipulating the human figure and composition. He learned the academic standards to know the key aspects to go against and to make a more powerful statement against tradition. Along with practicing sculpture, he immersed himself in cultural studies of non-European sculpture. He applied their primitive simplicity and apparent emptiness to his paintings, discovering a relationship between creativity and the human mind after being freed from reality.