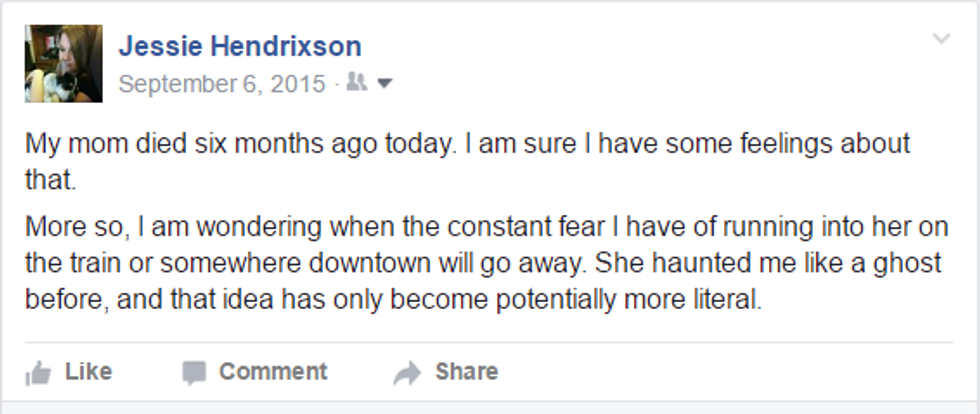

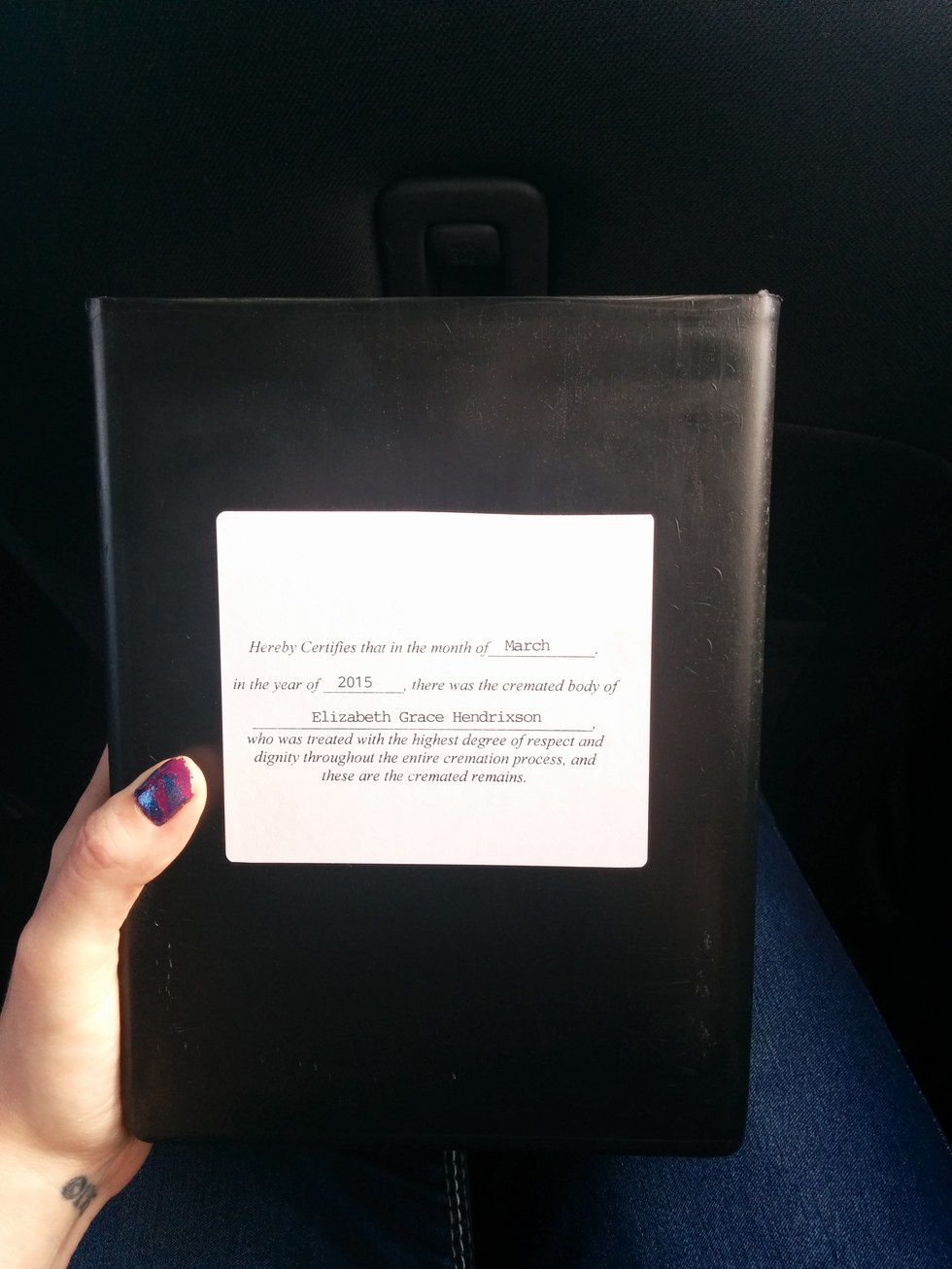

My mother died on March 6th, 2015. If this article is published on the date I believe it will be, that is two years ago today.

The official cause of her death was ruled "acute methamphetamine intoxication." In other words: an overdose. So go ahead and throw that in the face of those weird friends of yours who insist no one overdoses on meth. It happens. It happened to my mom. And meth was just one of her many addictions.

She was just a couple of months shy of sixty years old. She was alone when she died. And she left behind three daughters, a son, a (ex, but still involved and caring) husband, a dog, thousands of unanswered questions, millions of tears, and a path of destruction that rivals the likes of any war.

And it still haunts me.

So, I want to talk about the topic of addiction. And this is a tricky subject. Everyone who hears the word "addiction" will have an outward reaction of sympathy. But those who know addiction--those who grow up surrounded by it, have friends or family members that struggle with it, have a reaction that tends to be more visceral. It's almost as though we can feel sad for the stranger who struggles, but at the same time, we are angry with those we love who suffer in the same way. Because taking drugs is a choice, right? Because we think the addict is simply making a decision between us and their vice, and the vice always wins. And it becomes harder and harder to feel sad about it, and easier and easier to get angry.

And that had always been my mindset regarding my mother. Less about understanding, and more about anger.

Because the first time I realized my mom was an addict wasn't when she was passed out drunk at the foot of the staircase when she should have been picking us up from school. That was just overindulgence.

It wasn't when she was slamming beers while driving us to school, or when the cans whizzed

It wasn't when the police came to pick her up on what turned out to be a warrant for her arrest, when she locked herself in a footlocker in the shed out back leaving me, just ten years old and too young to be home alone, by myself to talk to the cops and ultimately be taken away and put under the care of the state. She just didn't want to be taken away from us, but it backfired.

It wasn't when she would disappear into the one functioning bathroom in the house for days on end, shooting up and tweeking out. She was just focused on her ridiculous art projects.

It wasn't when she crashed my dad's Toyota because she fell asleep behind the wheel--a result of several days of lack of sleep after a

And it wasn't when she went back to using the day--THE DAY--she left a two-year rehabilitation program.

Or when she would dumpster-dive for "treasures" to give to us on birthdays and Christmas.

Or when she'd steal anything of value from us, including gifts she gave us, to pay for her next fix.

Or when she'd have men in our house that, by law, should never have been anywhere near young girls.

Or when she had boyfriends while still married to my dad, and we just figured that's how love worked.

Or when she'd choose being around them over spending time with us and we thought that was just how being a mom worked.

Or, when seeing her for the first time in six years, she could only complain about her

The day I realized she was an addict was the day she died. When shooting up seemed worth it when she was on a combination of prescription heart medications. When her own health didn't take precedence, and she needed that high enough to die for it.

And only then did I start to search harder for answers.

But, as my third favorite band Misery Signals says, "Keep searching. The answers will never come."

I've made some realizations, nevertheless. And I realized that while addiction begins with a bad choice (or a series of bad choices), its claws sink in regardless of better judgment. It is a disease and the symptoms of it are as varied as the people who suffer from it. Which makes it all the more complicated to tackle.

Because no one pops their first pill, snorts their first line, melts down their first hit, or carefully taps the air bubbles out of their first needle with the intent to form a lifelong, one-sided relationship with a demon whose grip they may never be able to escape from.

It's so much more complicated than that, and when we pass it off in such a simplistic manner by attributing it to mere stupidity or selfishness or recklessness, we fail to see the deeper problem and we'll never be able to grasp onto or mitigate the epidemic that impacts so many lives.

And if anything of what little my mom told me about her life was true, and that's a big if, maybe she didn't know how to love because she was raised in an unloving place. Where violence was the only attention she knew. She disconnected. It was a defense mechanism. And she hid her heart behind everything, anything that could make her feel something. Anything.

I really didn't intend to air out so much dirty laundry in such a public format. And believe me, what's listed above barely begins to scratch the surface. But I know strangers don't want to be regaled with all the tales of my disturbing upbringing. And I prefer to avoid that kind of attention anyhow.

But somehow, I respect the lessons about life that she taught me by way of teaching me nothing worthwhile at all. Because I am who I am in spite of my mother, not because of her. Because children of addicts are eight times more likely than children with "normal" upbringings to become addicts themselves. And I, somehow, am okay.

So I honor her every day by living a clean life; a life she never got to

And I know it's important to talk about it. It helps to process the reality and severity of the situation so many people struggle with every day--both addicts and those who love them.

We have to learn to understand while protecting our own hearts. We can't take it out on ourselves.