In light of recent events at the Palm Beach Zoo and Conservation Society, and previous fatal events at SeaWorld, Zoo Knoxville, and other zoological facilities in recent history, the integrity of zoos are often called into question. Animal right's activists and "arm chair" activists alike fervently declare that all zoos and aquariums should be shut down and all the wildlife in human care released into the species' natural habitats or to sanctuaries. However, zoological facilities such as zoos and aquariums are important resources for the general public, the wildlife in human care, researchers and behaviorists, as well as the wildlife and wild places represented by the institution.

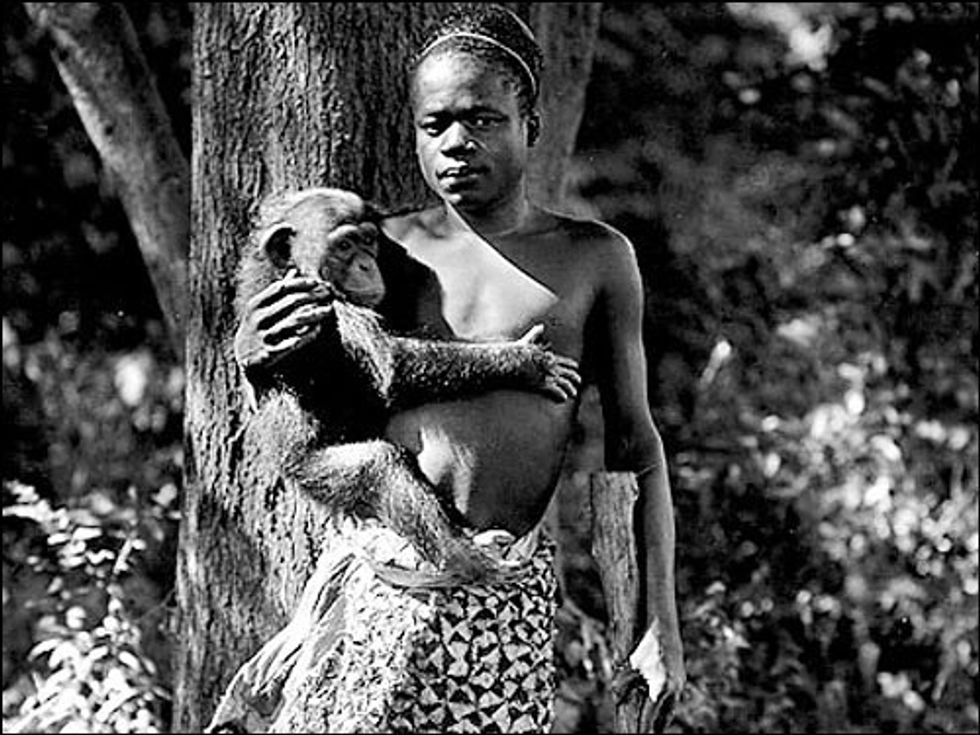

There is no doubt that zoos have a dark, not-so-distant past. In addition to wildlife, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, humans were often displayed. Such exhibitions were called "ethnological expositions" with intent of drawing a deep line between the "civilized" European societies and "primitive" African and Southeast Asian societies.

(Ota Benga, a human exhibit. Source: Wikipedia)

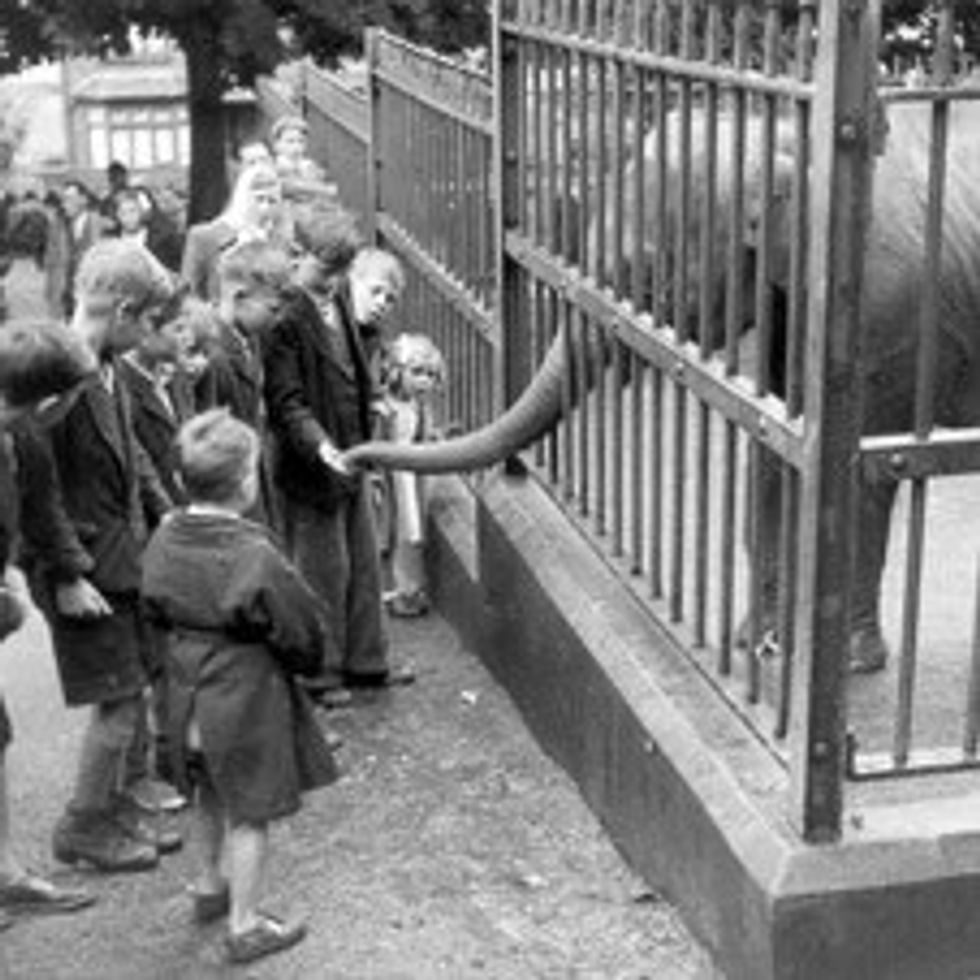

Up until the mid 19th century, zoos were private, meant only for the eyes of the rich and powerful. As interest in the natural world began to expand and science entered a new era of naturalism and ethology (the study of animal behavior), zoological facilities began to bring in exotic wildlife from all over the world to urban areas. Less about education and conservation, early zoos were centered around the idea of getting the public as close to these animals as possible. Non-human animals were considered little more than props placed down by a creator to serve the needs, whims and aesthetic pleasure of the curators and the general public. This resulted in small, barren cages, where animals could be fed and pet through the bars.

(Source: belfastzoo.co.uk)

Zoos have since come a long way. As research began to exemplify the intelligence of the animals in their care and the idea that human beings could in fact cause significant damage to wildlife populations (an idea previously widely dismissed), the perception of non-human animals began to change, as did the way and reason for which we exhibit them. Due to such research, both on animals in their natural habitat as well as those in human care, zoological institutions are vastly different than they were 116 years ago at the turn of the 20th century. Small metal cages and bars have been replaced by enclosures that represent and replicate a natural environment and provide daily enrichment for the animals they house. The animals themselves are no longer mere playthings or trophies picked and chosen for aesthetics, but ambassadors for their species.

(A male African Lion [Panthera leo leo] roaring in the middle of his carefully-cultivated habitat, meant to simulate a plains environment at the Bronx Zoo in Bronx, NY. Source: Brooke Dolega.)

In the United States, since the introduction of the Animal Welfare Act in 1966 and according to the document, facilities wishing to use non-human animals "in research, exhibition, transport, and by dealers" must comply with a set of federal standards for animal care to ensure welfare of the animals. As our understanding of the cognitive and emotional capabilities of non-human animals has grown since it's legislation, the document has been reviewed, edited, and adjusted in accordance with new moral and ethical standards. As well as complying with the Animal Welfare Act, zoos in the United States must also be inspected and licensed by the United States Department of Agriculture, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, the Drug Enforcement Agency, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Additional inspection, certifications and licensure may also be required depending on the species exhibited, including the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Act. Such thorough documentation is necessary for both the health and well being of the animals and the safety of their caretakers.

In North America, zoos and aquaria can also submit for accreditation by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (commonly referred to as the AZA). The Association of Zoos and Aquariums was founded in 1924. Since then, it has become the leading source of accreditation that a zoo or aquarium in North America can hold. For the past 92 years, the organization has been a leader in advancing the quality and purpose of zoos and aquariums through promotion of education, conservation, scientific research, and public interaction and engagement. They exemplify the standard of environment for wildlife in human care. To go to an AZA accredited facility is to be sure you are visiting an ethical, informative, and compassionate facility.

(Digital stamp of accreditation by the AZA that can be found on websites of accredited zoo and aquaria. Source: aza.org)

There are high standards and strict stipulations that an institution must comply with to be certified by the AZA. Each of these stipulations represents an essential component that benefits society, wildlife, and wild places as a whole.

First and foremost, the care and well being of the animals at the institution must be top-notch. The animals exhibited at zoos and aquariums are not simply there for aesthetics. Each and every animal is an ambassador for its entire species, as well as its natural environment. The animals are treated as such. Their exhibits are expertly cultivated to simulate the landscape which their wild counterparts inhabit, and are provided with environmental enrichment daily to ensure the physical, cognitive, social, and sensory stimulation that their wild habitats supply-minus the major stressors incorporated with everyday life in "the wild" such as unstable food supply and disease. Each animal receives a wholesome, nutritious diet and expert medical care. Their caretakers are well-educated and dedicated individuals whose main job is to work for the animals, not just with the animals.

("Polar Frontier" Exhibit at the Columbus Zoo provides both a terrestrial and aquatic environment for its polar bears, which are considered "Marine Mammals" under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Source: nassal.com)

Humans are tactile creatures with an amazing propensity for compassion. However, that compassion is often not founded from textbooks or television shows. Most find it difficult to care about a species halfway around the world or to worry about the destruction of land they have never stepped foot on. Zoos and aquariums facilitate a connection between those who may never leave their country, or even their home state. Keepers, caretakers, trainers, and educators at these institutions provide insight into the wild world, as well as inform the general public on actions that can be taken at home to help preserve the wild counterparts of the zoo's ambassadors. A popular saying amongst conservationists, naturalists, and other scientists alike is one by Senegalese forestry engineer, Baba Dioum: In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand what we are taught. Making a connection with an animal enacts compassion. That compassion for a species you might not have otherwise ever known about until the news headline reads that it has gone extinct, compels you to care about what happens to the animals' wild counterparts and more willing to work toward conserving wild places.

(A Siamang, [Symphalangus syndactylus] at the Palm Beach Zoo and Conservation Society in West Palm Beach, FL, sits on a log in its exhibit, looking for insects to snack on. Source: Brooke Dolega)

Research is also an essential part of a zoo or aquarium's institution as a whole. Many animal rights' groups may suggest that any research done in a zoological facility is not valid, because the environment is controlled. However, field research can be extremely difficult to conduct. The environment may not be suited to long term study, behaviors may be missed, or there might not be enough animals for verification of observations made. A zoo or aquarium environment allows for both the observation and verification of behaviors, as well as to view and experiment with behaviors that might not naturally be seen (such as recognition in mirrors). The information gathered from these observations and experiments benefit both the livelihood of the animals in human care, as well as their wild counterparts. Such research has lead to the better understanding of non-human animal cognition and sentience. This leads to both better care for the animals in human care as well as the advancement of societal views on the natural world.

(An Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin [Tursiops truncates] undergoes a test of object permanence at the Dolphin Research Center in Grassy Key, FL. Learn more here. Source: dolphins.org.)

Conservation is at the heart of zoos and aquariums. Though education and research are important components, population management and environmental protection is key. Many zoos contribute to global efforts. Examples include the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Palm Beach Zoo and Conservation Society. The WCS, which oversees the Bronx, Prospect Park, Queens, and Central Park Zoo as well as the New York Aquarium, also has "satellite" organizations in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the world's oceans. The Palm Beach Zoo and Conservation Society works with projects in Bolivia and Malaysia.

In addition to global conservation projects, members of the AZA also contribute to the Species Survival Plan, or "SSP". The SSP was established to create genetically strong populations of at-risk, threatened, and endangered wildlife.

(The logo for an animal species in a SSP program. Source: rosamondgiffordzoo.org)

Habitat loss is a leading cause of loss of species and diversity and many species currently live in greatly reduced or fragmented habitats. In case of human-related destruction or a natural disaster, there are populations in human care that could be used to reintroduce and reestablish wild populations when the environment is restored.

(A Malayan Tiger [Panthera tigris jacksoni] exhibiting claw-marking behavior on a log in his exhibit. With only 250 - 300 individuals in the wild, Malayan Tigers have an SSP with 64 individuals in the program in the United States. Source: Brooke Dolega)

Zoos and aquariums are critical to society, to wildlife conservation, and to wildlife research. Unlike many animal right's activists may try to convince others, zoological facilities are not the problem, but a solution. With wild places shrinking by an estimated 18 million acres per year, poaching and black market trade of wildlife parts still rampant despite the broadening legislation to combat it, and illegal pet trade and collection, zoos and aquariums are not a "prison" as some animal right's activists may suggest, but a haven for the animal ambassadors, for behavioral and physiological research, conservation of species, and preservation of natural habitat.

There are "bad" zoos out there. Roadside attractions, circuses, and "backyard zoos" or "backyard menageries" are akin to the zoos of the turn of the century. They contribute nothing to wildlife conservation, research, or education. Rather they focus on entertainment, fiscal gain, and greed. Such facilities should not be encouraged or supported.

To ensure one's entrance fee is going to conservation, education, and research, make sure you are visiting an AZA-Accredited or Affiliated institution. This information can be found on the institution's website, or you can check out the AZA's complete list of accredited facilities as well as a complete list of certified related facilities in North America. For international facilities, look for AZA-allied accreditations.