Before I came to study at Johns Hopkins, I lived in Peru for 11 years.

In Peru, I learned several things about the different cultures that called the country home. There is, of course, the well-known narrative of the Spanish conquest that holds reign over several aspects of the major Peruvian cities, particularly the capital, Lima; there is the pride we hold in the characteristic warmth and simplicity of the mountain communities (or, as we know them, the communities of the sierra) whose people are always bursting with song or with stories; there is the combination we see of the two everywhere–in our food, in our streets, in our literature. And there is also so much more of Peru than our history tends to represent, past the ceja de selva and deep within the Amazon.

The Peruvian rainforest, if you didn't guess, is a pretty fascinating place. Not only do we proudly form part of the group of countries known as "megadiverse" for the many different species of fauna and flora that we hold within and without it, but the Peruvian Amazon is also thought to be home to around 250,000 natives, comprising 215 ethnic groups with over 170 different languages. Many of these languages are dying–including the Shipibo language, which I will talk a little more about in just a moment.

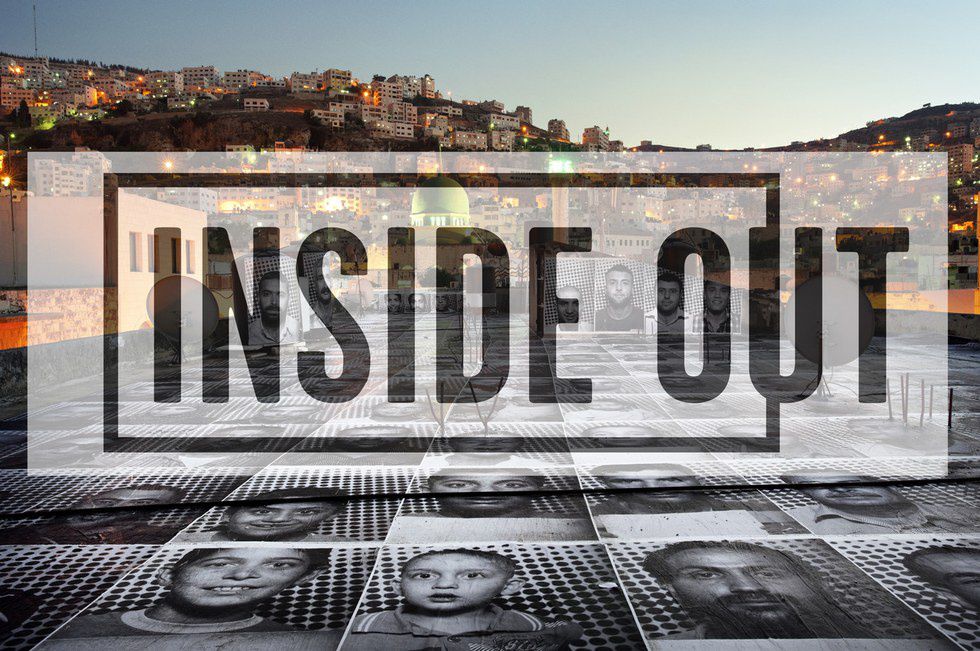

Anyways: Two years ago, my friends' visual arts teacher pioneered an adventure. We didn't have to go far away for it, not distance-wise, but it definitely taught us some unexpected skills and lessons. The objective? We were going to bring the Inside Out Project, a global photography project, to a small shanty town called Cantagallo.

The Inside Out Project has different forms of presenting itself according to location. In Baltimore, Md., the project was adopted as a means to express the #BlackLivesMatter movement. In Dublin, portraits of homeless people line the walls, reminding passersby of the importance of their lives and stories. In Fort Lauderdale, the project serves to celebrate the diversity of the community of students at Broward College. However, in 2013 the project had still had little exposure in developing countries, especially in pueblos jóvenes.

In Castilian Spanish, the term for shanty towns like Cantagallo is pueblos jóvenes, which literally means "young villages." In a way, Cantagallo fit the term perfectly. This town was exactly like a child; still unstructured and dirty, still pure in character and in life. However, the people living in Cantagallo were also extremely unique.

The group of people living in Cantagallo was largely Shipibo-Conibo. The Shipibo-Conibo tribe, originally two separate groups before performing a series of communal rituals and intermarriages, represent about 8 percent of the indigenous registered population in Peru. There was not a particular reason in common, as is usually the case with displaced peoples who need to choose a new homeland, why such a large group of Shipibo-Conibos decided to travel all the way to the capital of Lima. Living on the banks of the highly contaminated Rímac river is certainly a radically different reality from their homeland by the Ucayali river, which is one of the main headwaters of the Amazon.

The families I spoke with told me that their decisions to leave Ucayali were mainly influenced by Western pressures, whether these be the threats of nearby oil extraction and logging, or the even worsening menace of jungle narco-trafficking. However, they were also reluctant to admit that they had had extremely high hopes for their new lives in Lima, and just like most rural-to-urban migrants, ended up discovering that the city was struggling with overpopulation and low availability of resources. In short, they expected to feel welcome, and were more than betrayed by their expectations.

The Shipibo-Conibos, however, had the upper hand when it came to one thing: their craft. The tribe had already been known throughout Peru for their beautiful textiles and elaborate clothing and jewelry designs. When they came over to Cantagallo, they were forced to make themselves houses out of cardboard, or flimsy wooden panels, or woven straw, on dirt that was not only uneven, but also so polluted it gave the children who played in it a variety of infections. However, they still exhibited joy and hope for a better community, and this was reflected in their street art.

With Inside Out, the goal was to bring out one of the most beautiful parts of the community–its children–and hang pictures of them around the neighborhood in order to celebrate them. We organized an arts festival in which a team from my school hung up the pictures, while I led another team in teaching children to make little crafts from things like bottles and toilet paper rolls. This brought a lot of media attention, which helped to incentivize the local municipality to get the project "Río Verde" moving, which would aim to relocate the community to a Lima neighborhood with a less polluted environment for the sake of the people's health. However, there is still the lingering fear that a new administration may cancel or pause the project indefinitely, which would be even more damaging to a community that is consistently being taunted by the hope for a better lifestyle.

While the people of Cantagallo perhaps do not fall under the definition of an internally displaced people established by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)–"[a people who have] been forced to flee their homes because their lives were in danger, but unlike refugees they have not crossed an international border"–their plight is still deserving of recognition. Seeing the struggle they endured, especially as represented through their art, made me think of all the people in the world that have had to leave their homes because it was no longer safe there, and/or because another place seemed to offer a better standard of living.

Problem: Language. Solution: Art.

One of the largest problems IDPs and refugees endure in their host communities is the communication barrier, especially if the group in question does not speak the language of the place they are forced to move to. This frequently leads to a social unwillingness of the old community to help the new, often resulting in segregation.The language barrier has been seen to affect displaced populations all over Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Kosovo, to name a few. Children tend to suffer from this the most, since they often lose a chance at education if they speak another language, limiting not only their employment opportunities in the future, but also their chances for local integration and emotional welfare in the present.

One of the benefits of the visual arts is that it deals with images that are universal. Even Cantagallo's mystical portrayals of jungle animals appealed to a sense of warmth and inherent Peruvian diversity that we, as fellow Peruvians, found it easy to want to encourage. If refugees and displaced people are given the opportunity to express their feelings regarding the struggles they have needed to endure, in the present as well as in the past, through a means that locals may understand, sympathy is much more likely to follow. And from that sympathy, comes the fulfillment of basic human needs and rights, appreciation, and support.

Problem: Need. Solution: Art.

Sometimes needs are more than basic, however. A people may be politically unrepresented, a people may be famished or injured, a people may still be persecuted. A people may need to cry out to those around them to help them, and even if they speak the same language, sometimes a lack of empathy still needs to be addressed for help to be given when it's needed. Art can express need in the most impactful ways, and with the right amount of media coverage it can call attention to people far past the confines of a neighborhood or district.

Problem: Grief. Solution: Art.

And then there's my favorite part about art: While it allows the person on the receiving end of a piece to become enriched, this doesn't occur at the loss of the artist. On the contrary, the artist is always further inspired by his own art, (however ridiculously hipster-ish that just sounded) and so they will continue to seek for help. They will continue to find pride in their people. They will carry on.

Art can be the most infectiously constructive coping mechanism. People who have escaped war, or social unrest, or extreme conditions have a lot to say about their previous and current circumstances. There is a lot of trauma, a lot of loss, and a lot of stories to tell. Art enables the IDP/refugee to speak out, to ask for help, and to mourn their losses all at once. And sometimes when they do, as in the case of Cantagallo, there is a response.

To read Al Jazeera International's story on the Shipibo-Konibo people of Cantagallo: http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/7/24/th...