Those who grew up during the Civil Rights Movement and/or Apartheid know what it is like to live in a black and white world. It is common knowledge that pale skin reaps benefits whereas dark complexions can cause torment.

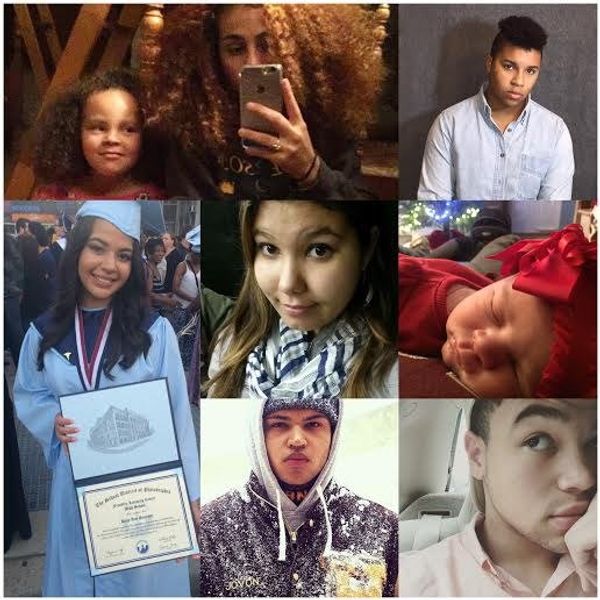

But, what can you expect of a person who cannot identify with either black or white identities?

Maybe they are dark, but not too dark, pale, but not too pale. The existential race crisis is a rite of passage for every mixed child. Through history we have been called "mulatto," " half breed," "oreo," "zebra," hybrid," "mutt." I have personally been called "caramel" way too many times.

However, names like these do not categorize us, far from it. What occurs instead is a confusion that spins mixed children into a frenzy of blurred self-identification. On one side, there is a white parent, on the other, there is a black parent. If I love them both equally, is it possible to side with one identity more so than the other?

There are many other circumstances that dictate the outcome of my exhausting racial ordeal. For instance, being raised by a single parent will definitely alter a mixed child's views of the world. After being exposed to only one side of their genetic makeup, they tend to identify with the culture they were brought up with. However, this is not a matter of fact occurrence. Skin color plays a prominent role in the inner workings of racial identity. In cases where the skin color of the child is vastly different from their sole guardian—to the point where strangers could never make a parent-child correlation—there can be a shift of identity as the child develops.

My mother is an African-American woman. As a baby, my mother would push me in a stroller around our neighborhood, she told me about pedestrians who would strike a conversation with her and then become surprised—shocked even—when they came to find that I was her daughter. Many would go on to confess they thought she was my nanny.

When I was younger, it never occurred to me that I was part white. I had a black family, so it was inferred—to me—that I was black. As I got older and compared my skin tone to family members, it dawned on me that I was different.

Going to schools where the majority of students were minorities, I thought of my light skin as a weakness. To make up for it, I would try extra hard to "be black" so I could fit in. I listened to hip-hop, learned slang and always made sure I was wearing specific items of clothing to help me fit in better, and I also avoided hanging out with white children. During junior high, I carried around a picture of my mother as proof that I am indeed black.

It was not until my senior year of high school that I realized how unhappy I was. Reinforcing stereotypes in exchange for acceptance looked futile and stupid. I know I am African-American, but I am also white. Just because I never knew one side of me does not mean I am not a part of it. There is no just definition of what it means to "be black," because blackness is so diverse and encompasses so many different experiences.

And, to base my role in the world solely on my skin color is horrible. It is an epidemic that has gone on for too long.

Bill Nye said it best: "We all came from Africa. We are all of the same stardust. We are all going to live and die on the same planet, a pale blue dot in the vastness of space. We have to work together."