Potentially life-changing science experiments are sometimes seen as crazy, and the scientists who perform these experiments seem even crazier, yet sciences continue to exceed even the worlds wildest expectations. You can check some of them out on this website. History makes it clear that sometimes an unconventional idea can lead to unthinkable innovations in technology, medicine and psychology. In other words, "crazy" people help us understand ordinary people. So, where do we draw the line between what kind of incredible experiment could potentially benefit the human race and what could potentially cause problems the world never saw coming? How do we know when an experiment has gone too far?

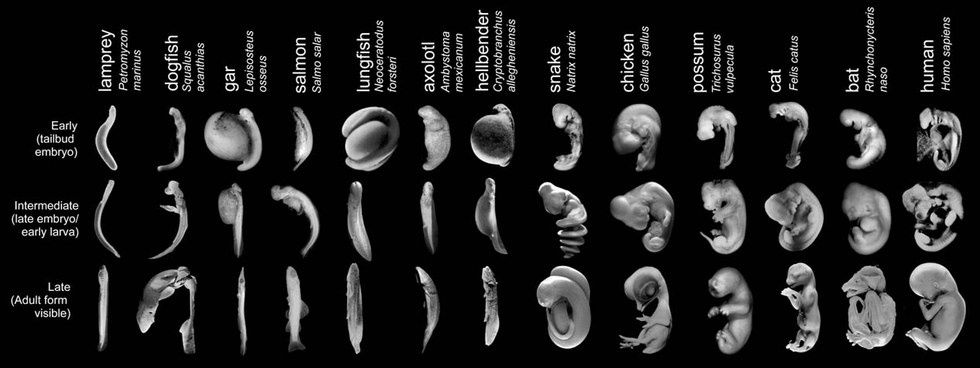

An article by Rob Stein on NPR titled, “NIH Plans to Lift Ban On Research Funds for Part-Human, Part-Animal Embryos” explains how, on August 4th, the National Institute of Health lifted its ban on government funding for an experiment that will use human stem cells to create human-animal hybrid embryos (chimeras). This type of science could lead to a myriad of answers concerning human disease. For example, if cows or sheep could survive with human organs such as hearts, livers, kidneys and pancreases, they could possibly be used for human transplants and save thousands of lives. Experiments involving animals with human brains and tissues would allow scientists to closely study neurological conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s diseases. Experiments involving animals with human sperm and eggs would allow scientists to study human development and infertility (Stein). But what are the dangers of animals gaining some kind of “human consciousness or human thinking abilities” (Stein)? What are the ethical concerns? How could scientists be able to control such a risky experiment?

First off, the new policy introduced by the National Institute of Health will prohibit experiments involving human embryos and animals that closely resemble humans, like monkeys and chimps. A nonhuman primate with the ability to develop a human-like brain could cause problems concerning human consciousness in smart animals, which would have its own set of ethical issues. Additionally, there is a concern with breeding, so regulations would have to be made in order to prevent human-animal hybrids from producing offspring.

The National Institute of Health’s associate director Carrie Wollinets stated during an NPR interview that, “At the end of the day, we want to make sure this research progresses because it’s very important to our understanding of disease. It’s important to our mission to improve human health. But we also want to make sure there’s an extra set of eyes on these projects because they do have this ethical set of concerns associated with them.” People on the other side of the spectrum disagree that this type of science could be beneficial, comparing it to science-fiction novels like “Frankenstein” and “Brave New World”.

In an International Business Times article by Vittorio Hernandez titled “At UC Davis, maximum period for chimera embryos is 28 days & adult chimeras can’t mate,” he reports, “MIT Technology Review reported in January that human-animal chimeras are gestating on US research farms. It interviewed three teams, one in Minnesota and two in California, and estimates there are about 20 pregnancies of pig-human or sheep-human chimeras in the last 12 months.” The embryos were obviously never fully developed because the maximum period for development, as stated in the title, is 28 days, but this gives scientists enough time to extract animal cells and insert human ones. Despite the fact that these experiments are being done in private, some researchers are already seeing results from their experiments that could potentially help people find cures to human diseases and conditions. For example, “Another researcher from the University of Minnesota showed images of a 62-day-old pig fetus in which its congenital eye defect was reversed after human cells were added” (Hernendez).

According to Stein, “the public has 30 days to comment on the proposed new policy. NIH could start funding projects as early as the start of 2017.”