The Hudson River School of Art offers a look at America's first artistic movement. Its 19th-century pastoral landscape style and appreciation of the environment is important in today's digital age and climate concerns.

English immigrant Thomas Cole has received the honor of founding the movement, which begins upon his 1825 New York City arrival. Literature, often a precursor to subjects of art, had a dedicated interest in nature at this time. Naturally, Cole had aspired to paint landscapes and used previous American artists for reference from time spent in other states. Cole did not abandon his national origin, and it is visible in his style. Celebrating Romanticism's hazy lustful colors and the British tendency to intensify nature are evident.

By this time, Europe was dominating the art world. It was a hub for movements, techniques, and academics. Creatives flocked to its bustling cities, hoping to get work and fame. America had idled by and was more of a gracious consumer and observer. This shows what immigrants bring: a diverse and different approach. Producing art was natural to his home country, where the likes of J.W. Turner hang on walls today and was an idol to Cole.

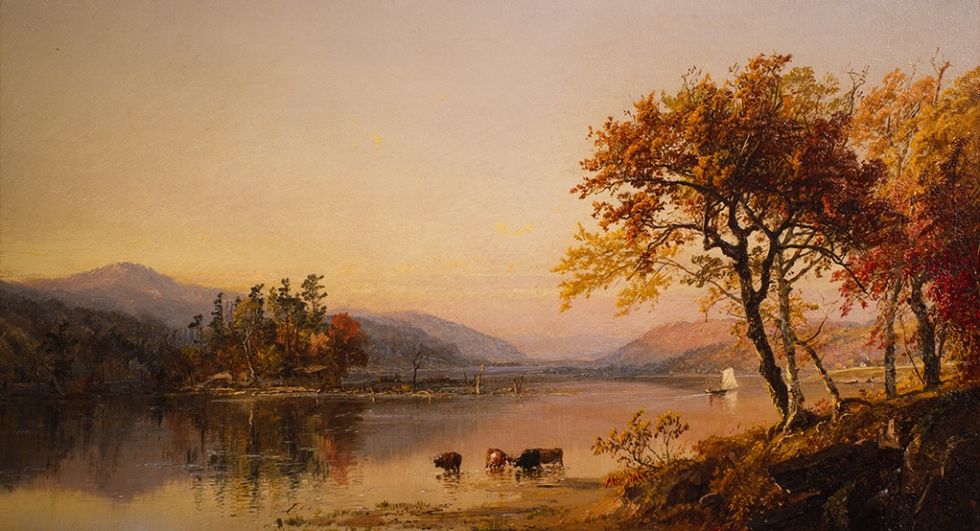

Most of its 25 to 50 artists belonged to the National Academy, where they attended the same organizations and worked in proxemics. They have been likened to the first art fraternity. The Hudson River would come into play when most choose to relocate there. Like its namesake, these artists did depict the Hudson River in their work. However, the name itself is rather unfitting. This movement is far more than that. Areas and subjects were quite diverse, including the Catskills and Adirondacks mountains.

Running in sync, the Erie Canal had just opened to the public, allowing for travel into new territories. Passing through the grounds had impacted some new to the entire country. Paint tubes did not exist yet, which meant artists worked from recollection in their studios. The resulting creations explore the peace nature offers, life without humans present.

Solitude and serene landscapes track dancing animals playing amongst themselves. It is an ode to our roots, retreating from the increasing industrial age of machines and pollution. There is immense simplicity, staying within the realm of realism. This counteracts with art breaking at the seams, seeking to elevate art as more than documentation.

Works were made by venturing out into lands of grass and flowing trees and keenly observing what awaits them. Nature was the model. The delight from readings of others' journeys into an unknown land and the spiritual connection with Earth's boundless and neutrality fueled these artists. It was very much a soul search to them and the act of seeing played in just as much as the painting itself.

Not all scenes, however, actually existed. Again, this was done to wish away mankind and reimagine lands desecrated by human expansion or litter. Landscapes had been known to artists for ages, yet it remained an under-explored topic. From Ancient Greeks depicting Olympian Gods to the Renaissance painters humanizing religious texts, the narrative was prized. Here, a subject is clear but there is no typical action.

Forest and mountains in everyday life were seen as prime land to build houses on and domesticate. Having a philosophy that untouched nature was majestic, beautiful and not to be feared countered American society. Trees were something to gaze upon and hear sway, not be chopped down for new paper. The Hudson River School of Art would be credited with validating wilderness to Americans.

Women would find time to shine here. Art was a profession only to men, and academic teaching on the likes of shading and tone mostly rejected women. To the schools, admitting women would be wasting a seat since they had no career potential. Furthermore, nude figure drawing classes did not allow females, causing those lucky enough to be educated to miss out on important anatomical knowledge.

This certainly did not dissuade some women, who managed to get under the wings of Cole and educator Fitz Henry Lane. Painting was an act of presence for these women and as close as they could get to being artists. Their works, however, have been left out of major tellings of The Hudson River School of Art until recent decades.

As usual, this movement would end. Its ending would follow the Civil War, a shift from British to French cultural admiration, and figures again dominating subject. Attention to The Hudson River School of Art has fallen in and out of flavor. A resurgence, however, has been found in the 21st century. Passion to preserve what is seen and admiring nature's fragile existence is attributed to growing environmental concerns.