In high school, I was acquainted with the "Hobbes vs. Locke" debate on human nature. Locke thought people were naturally reasonable, while Hobbes thought people were naturally evil and selfish. Seemed like a pretty simple world.

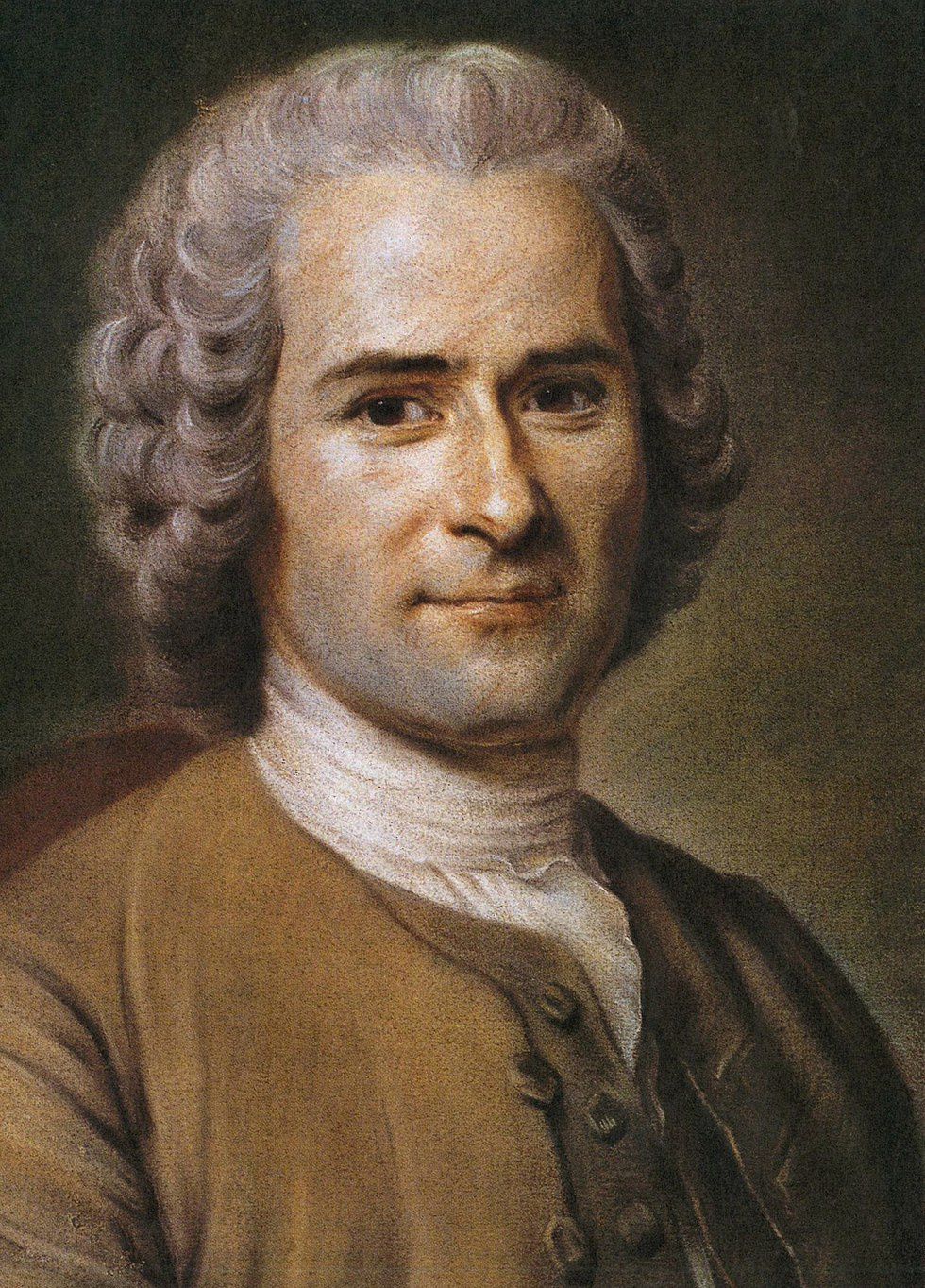

When I got to college, however, I met a whole new player in this game: Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Although I haven't read Rousseau's work on "The Social Contract" just yet, I read his "Discourse on the Origin of Inequality." In this essay, he theorizes that men were born equal, and the advent of civilization is what corrupted man and equality.

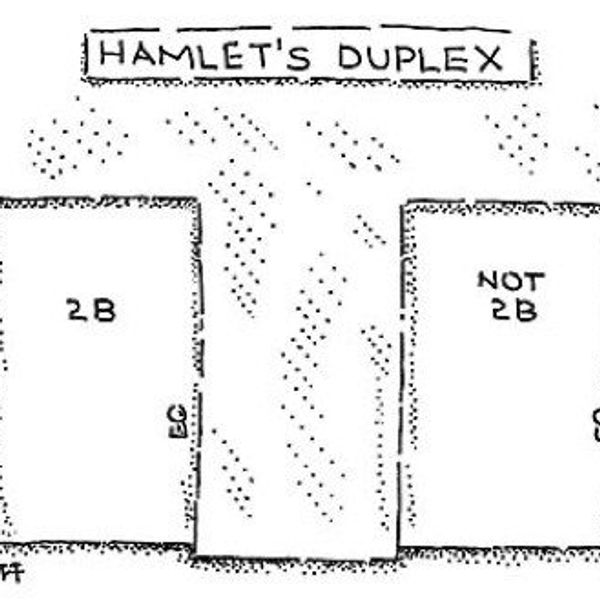

Rousseau constructs an image of the noble savage (the idea that savage man is not evil), and the state of nature as the most ideal state. What's interesting is that he does so by destructing Thomas Hobbes’s argument about human nature. Taking down Hobbes's argument is really crucial to Rousseau because if he can't prove that savage man is not evil, then he can't prove that the state of nature was way better than life is now (or life was during his time).

The issue with Rousseau's argument is that he doesn't exactly have empirical evidence. It's not like he can go back in time, hang out with some guys who live in the state of nature and report that they're the best. This lack of evidence means he needs to rely on his rhetoric to take Hobbes's argument down, and as such, he uses some really interesting techniques.

First, Rousseau doesn't really represent Hobbes's argument by itself, but only represents it in relation to his own argument. From his introduction of the opposing point, Rousseau already has a leg up. He systematically overshadows Hobbes’s argument with his own and takes the lead with his thoughts. This shows that Rousseau has his own argument and that he is not reactionary. This, in itself, decreases the importance of Hobbes’s argument, as Rousseau is not writing purely to negate Hobbes but to express his own sentiments. Rousseau wants us to think of Hobbes as a footnote of sorts that Rousseau needs to dismantle in addition to expressing his own argument.

Rousseau also initially agrees with the basis Hobbes puts forth, but disagrees with the conclusion drawn from it. For example, he first states that “man has no idea of goodness,” a principle both he and Hobbes agree with. However, Rousseau then puts forth the idea that this is not synonymous with the idea that man is “naturally evil.” In fact, he agrees with Hobbes's first principles about a lot of things, but negates the conclusions. Although some of Hobbes's analysis is correct, Rousseau says that only he can reason properly from this definition and, therefore, establishes the superiority of his argument.

Rousseau emphasizes this superiority by indicating that Hobbes did not even “reason on the basis of the principles he establishes.” He even puts words in his opponent’s mouth, declaring that Hobbes "would" have agreed with Rousseau if he had reasoned correctly. If only Hobbes was as logical as Rousseau, there would not even have been a disagreement, which nulls the idea of Hobbes’s argument from its inception as his argument would have been the same as Rousseau’s.

Rousseau then reaches the meat of his argument, where he quotes Hobbes and attempts to use his own words against him, saying “The evil man, he says, is a robust child.” He, then, attempts to disprove that the “savage man is a robust child” and, by extension, that savage man is evil. His technique here is oddly mathematical; he uses a proof by contradiction, where he insincerely agrees with Hobbes and then shows that if what Hobbes is saying would be true, something impossible would happen. Because of this impossibility, Hobbes must be wrong, and Rousseau must be right. In Rousseau's case, these impossibilities are grotesquely extreme. He says if man were truly evil, "he would beat his mother, were she too slow in offering him her breast; he would strangle one of his younger brothers, should he find him annoying." This seems a little intense. Rousseau is exaggerating by using violent and ridiculous images to belittle Hobbes’s argument. Because Rousseau is unable to demonstrate his contradiction empirically, this rhetoric will just have to do.

So, although Rousseau seems kind of unfair, he shows us that we can be more convincing by enveloping an opponent's argument with our own, making their point seem insignificant, using their own words against them and then deriving a contradiction from a situation where we accept (hypothetically, of course) that they were correct. On the one hand, these techniques make for some pretty good ways to take down an argument, especially when you don't have all that much evidence. On the other, they show us the extent to which words can influence us, and how failing to think about them can cause us to be convinced by something that might not actually be true.