I have always had a knack for history; the Holocaust has always been one of the most interesting topics to study for me. When my family took a trip to Washington D.C., we made it a point to visit the Holocaust Museum. I expected the museum to reiterate all of the information I already knew, but I was so wrong.

To see the permanent exhibit, you have to have a ticket. When we got ours, we saw that we had a couple of hours until our tour started, so we went and toured the exhibits that you didn’t need a ticket for. This is where a lot of the information that I already knew was held- so what could possibly be in the permanent exhibit?

Finally, 2:30 rolled around and we got in the long line to go into the exhibit. Once they scanned our tickets, they told us to pick up an identification card and not to read it. Already this was so different from any museum that I had ever been to.

When we got into the elevator, the attendee told us that we were only allowed to look at the first page of our identification card. Everyone in the elevator eagerly opened their cards. Inside was the name of a person who had been involved in the Holocaust. Under the name was a small biography of the person whose role you were supposed to take for the day.

Throughout your journey through the museum, your identification card would tell you what was happening to that person at crucial times in the war. At the end, you found out if you lived or if you died.

The museum itself was spectacular. Not only did the walls tell the story of the Holocaust, but they also provided visuals and tactile of what it was like to be there. There were the striped pajamas of the prisoners, family heirlooms that had been ransacked from the Jewish people before they were taken to the concentration camps, a model of a train car that took Jewish people from their homes to the different concentration camps, a sign that read “Arbeit Macht Frei,” and, the most chilling, the hair that was shaved off the dead before they were incinerated and the shoes that were stolen from the prisoners before they died.

To walk through the museum was a haunting experience, but what made it seem real and left the greatest impact was the identity of the person on your card. The name that I got was Catherina “Ina” Soep, whose father was a diamond manufacturer and president of the Amsterdam Jewish Community. When I read this, I thought that I (as Ina) was going to die, simply because of who her father was. I guessed only time would tell. In 1943, Ina and her family were taken to the Waterbork camp, where eight months later they were transferred to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Her family’s saving grace was that the Nazi’s decided to build a diamond industry there, and needed experienced Jews to work there. Because of this, her family wasn’t sent to the death camps. When German defeat was obvious, they abandoned the diamond plant and loaded Ina and her family onto a train heading west, which was saved en-route by U.S Troops.

She was safe.

But that was not the case for many others.

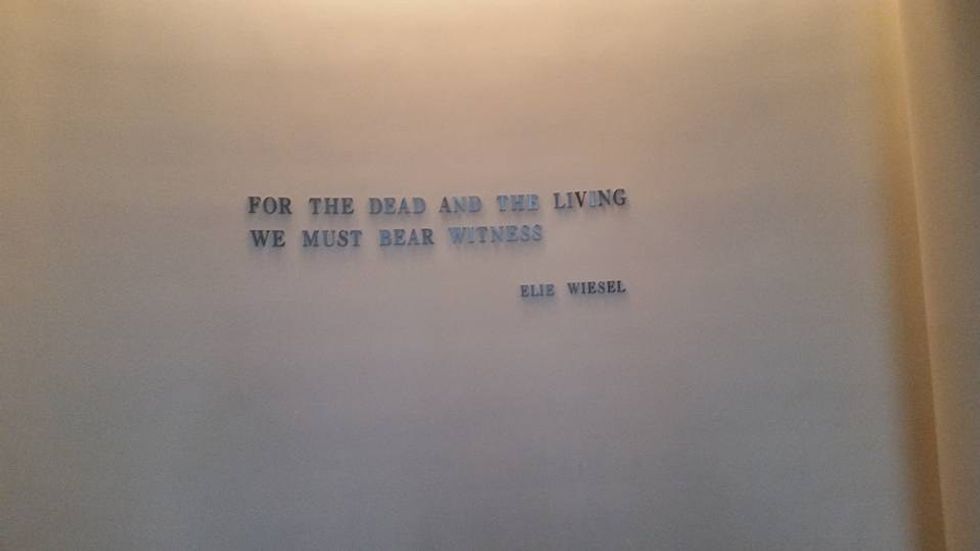

“For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.” –Elie Wiesel

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by