For as long as I can remember, I have been my own worst critic. When it comes to myself, I have been a harder disciplinarian than my parents have ever been. There is a drill sergeant inside of my own head telling me to work harder, be smarter, and act better. I compete with not only everyone around me, but with my own personal best. Although this drive to be the best person I can be has manifested into good grades, awesome opportunities, and a slew of awards and accolades, it also began a life long battle with my eating disorder.

When I was 17 years old, I was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. I was sad, frustrated, and scared that what I thought was drive and perseverance actually turned into a serious disorder. I couldn’t stop watching my weight, watching my diet, and watching the mirror. I had convinced myself that I was being strong and strict, building the best body I possibly could; that was until I started having trouble finishing a flight of stairs without losing my breath.

To this day, the moments leading up to my diagnosis are a blur because of the guilt and humiliation I felt. I believed I had let myself down; I felt ashamed to be one of “those girls” who saw therapists and visited the hospital for illnesses that no one could see. I believed the doctor was merely for visibly sick people, a last resort when all other options failed. The hospital was a place for the brave people suffering from cancer, tough people who broke bones, or those with bad enough luck to catch a virus. This “disorder” did not fall into my checklist of things worthy of medical sympathy.

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, up to 30 million people in the US suffer from an eating disorder. Also, anorexia is the third most chronic illness among adolescents. With these statistics, it is almost appalling that talking openly about having one is often looked at as taboo. There are so many misconceptions surrounding the topic, and I realized that the shame and depression I was feeling was caused by society's warped view on what it really means to have an eating disorder.

I always assumed people with anorexia were weak and superficial; I associated the disease with supermodels and rich teens seeking attention. I never thought that a sassy, Beyoncé obsessed, 16-year-old black girl could be anorexic. The thought that I was afflicted with an invisible illness reserved for the frail and transparent spiraled me into a deep depression. For a long time, only my family was aware of my diagnosis, but even with them I never spoke candidly about it. A few close friends noticed a change in my weight and eating habits, but I kept quiet, making it my own personal elephant in the room.

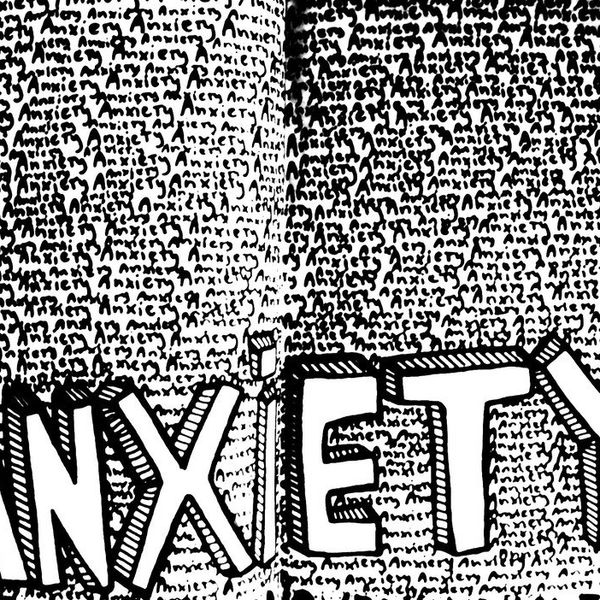

My shame and guilt made the beginning of my journey with this disorder and extremely uphill battle. The fact that I couldn’t look at my physical self in the mirror on top of the hatred of my own mental health caused me to go to one of the lowest and darkest places I’ve ever been. For months I was afraid to be alone with nothing to do because the thoughts in my head scared me more than anything ever had. I looked for acceptance, love, and validation in every place but my own heart. I became smaller physically and mentally because I was afraid to consume too much space out of my guilt of not being the best person I can be. In my mind, I felt that I didn’t deserve to occupy my surroundings. I felt like a failure.

These feelings continued up until the time I began college at Kent State University, when I decided that I had no other choice then to make a change, or else I would not be around to experience life at my full potential. I met some of the most beautifully inspirational people and became close to one of the greatest friends I have ever had. I reached out more to my family and I researched about other people in the same position as me. Most importantly, I began to talk. At first it was awkward; any time I was formulating a sentence explaining that I have anorexia, I could feel my palms sweating and my face turning red. I was paranoid of people forming negative opinions about me, believing that I was weak and superficial. Instead I received overwhelming support that truly changed my life. I no longer had to be alone on my journey; I had friends and family that lifted me up and reminded me of my worth. My biggest regret is internalizing my feelings and isolating myself for so long when there were so many people who could have helped if they had just known.

Today I am a lot more stable than I ever have been in terms of the acceptance of my body. I do not get nervous talking about my struggles with eating, and I always have someone to vent to when things get rough. Anorexia is not curable; it is something I will deal with until the day I die, but now I have help to ease the pain and make life so much more bearable. I do not ever want a 16-year-old girl to feel like her problems aren’t important enough or to feel like she isn’t worth support and love. Eating disorders do not have a type, anyone can be affected regardless of age, race, or gender, and it is time for society to realize that.

I hope that by sharing my story, maybe one more person will have the courage to share theirs too.