If I were to ask you, "Who's winning in the war on drugs," how would you even respond?

Give it a second. Think about the possible "sides" of this war, and where you think you might stand on the issue.

The question in mind, let's dive into a little background on the topic confining our scope to just the U.S.

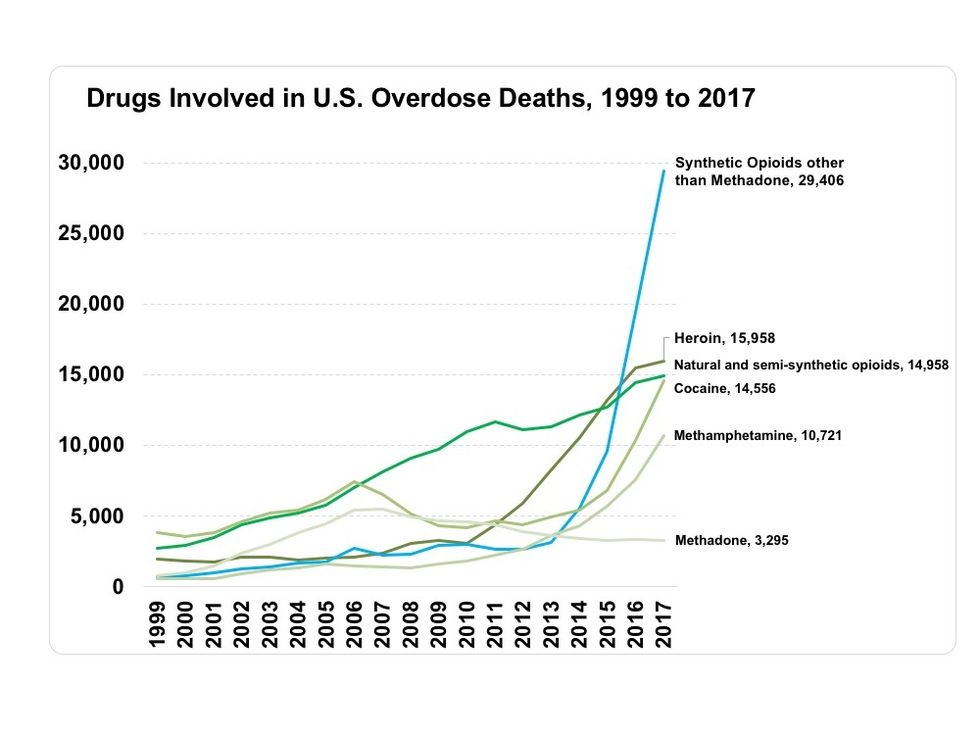

In the past year alone, more than 72,000 Americans have died of drug overdose or substance abuse-related symptoms.

72,000 lives in 2017.

A number you might not have necessarily known, but given contemporary times, probably doesn't shock or impress you. Actually, it might even relieve you, knowing that overdose is only the 8th leading cause of death in the U.S., nestled right between diabetes (80,058) and the flu (51,537).

But what might surprise you is learning just how much of the population struggles with addiction, specifically some form of substance abuse.

In a study conducted by the U.S. Census, in 2013, out of the 24 million Americans who have admitted to illicit drug usage, 19.6 million of them have reported dealing with a substance abuse disorder in the following year.

That's 1-in-10 Americans, who have openly admitted to having an addiction disorder in 2013.

Undoubtedly that number has only increased since 2013, as our country continues to struggle with the recent "opioid epidemic", which abuse has skyrocketed in only the past couple of years.

But to circle back to our original question; "Who's winning the 'war on drugs'?".

...To be honest, who knows?

But it's definitely not us.

But let's take a step back from the whole "war" ideal and focus on how we perceive addiction and how we think it begins and occurs in us.

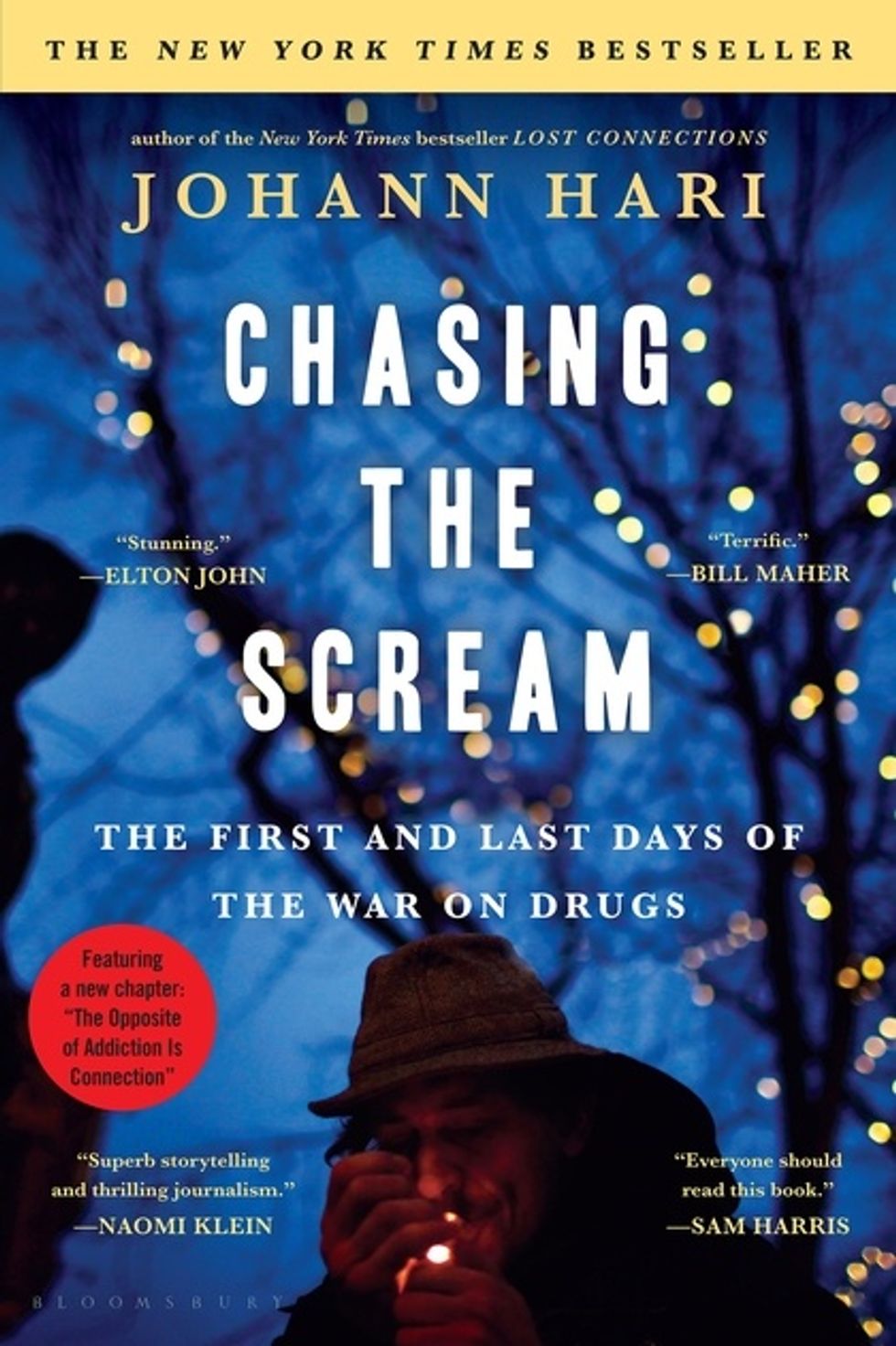

In a recent book written by British writer/journalist Johann Hari, "Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days on the War on Drugs", Hari sets out to explore the history and impact of drugs on the modern world and the perceptions of addiction and how addiction originates.

If I were to start using heroin right now for twenty days straight, by the twenty-first day, my body would most likely develop a physical attachment to the drug and would not be able to operate normally without said substance.. and that's what we know to be an addiction, right?

Turns out, there might be more to addiction than we thought.

In a study followed by Hari in his book, ten patients admitted to a hospital with similarly severe injuries were given a medication equivalent to potency and effects of street heroin, known as "diamorphine", for weeks and months on end. According to our national statistic, when released from the hospital, at least one of those ten patients are bound to develop a substance addiction right?

As it turns out, this particular study has been closely observed repeatedly and earning a trip to the hospital after breaking your hip and ingesting a lot of legal heroin doesn't increase your chances of gaining an addiction to a substance.

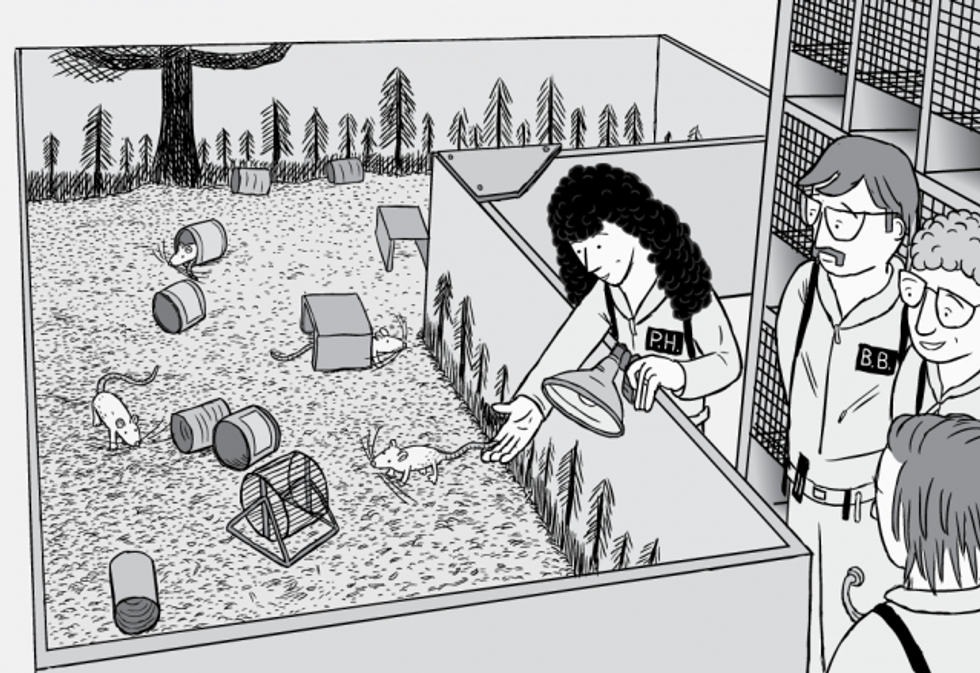

Hari's theory of addiction starts with the famous "Rat Park" experiment.

To give a concise summary of the experiment, the observations go something like this:

- In a previously popular experiment, a single rat was placed in a cage with two bottles - one with regular water, the other a solution mixture of both cocaine and water. In almost every single case, the rat will choose the drugged water over anything else until it dies.

- A psychologist named Bruce Alexander observes that the rat in each of these experiments is alone and has nothing else to do but ingest the drugged water. Alexander proposes a modified version of the experiment: place a whole family of rats in a larger observational platform, complete with toys, tunnels, and shelters, where the rats were free to socialize and live freely. The two bottles were still given the same.

- Interestingly enough, in this new rat utopia, the rats hardly ever use the drugged water - none of them use compulsively, none overdose.

But maybe it's a rat thing?

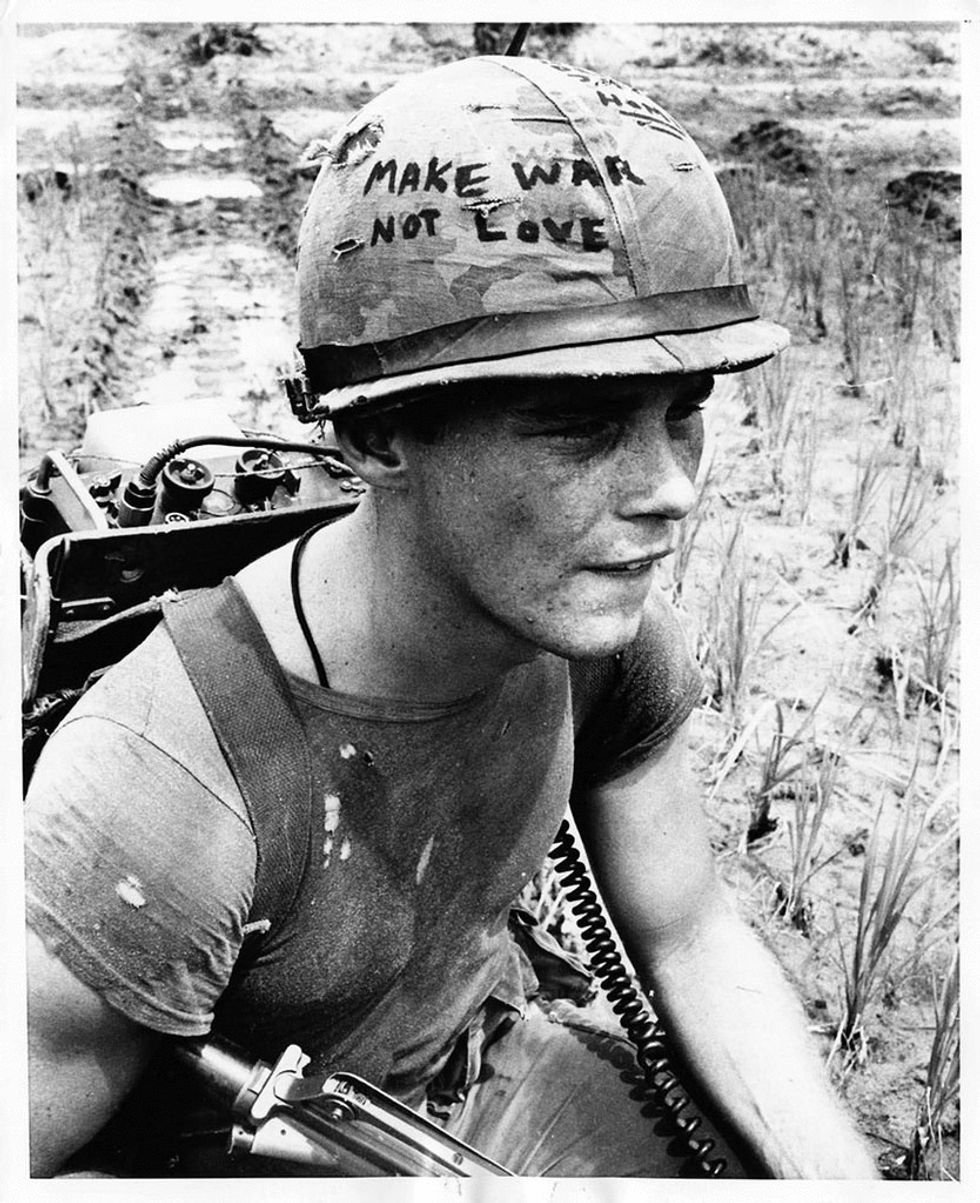

Hari alludes to the Vietnam War for a more human parallel.. ~ 20% of US military forces reported heroin abuse during the war. In fact, narcotic abuse was so prevalent within the U.S. military that when American public gets wind of the sweeping epidemic of drug addiction, citizens begin to panic towards the end of the war and predict an influx of junkie troops poisoning the general "welfare" of a largely ungrateful nation.

Though what the public couldn't predict was upon the troops' return, around 95% of reported abusers stop using.

No rehab, no withdrawals.

Now if we adhere to the aforementioned common theory of addiction, these results just don't make any sense. How does an addict stop cold turkey after years of abuse?

In places such as Vietnam during the conflict, we often hear often stories about soldiers living in a jungle-themed version of hell, where any moment could have been their last. Soldiers turning to drugs seems like the most visceral and accessible way to escape the morbid reality that war actually is.

Though if we are to embrace this new theory of addiction, this all starts to make more sense... moving from a living hell to the loving embrace of your home and family.. a desolate and lonely cage to a miniature rat utopia...

We begin to see that it's not really about the chemicals in your body, but more about the cage.

We as human beings are social creatures. We need each other for more than survival, we need each other to be happy! (whether we'd like to admit it or not..)

When we are healthily happy, our desire to love and bond with one another is automatic - we are often driven by our needs to bond. But when we are "put in a cage" or otherwise isolated, ostracized, or traumatized, we search for other things to bond with - whether that be some other "escapes" from reality, such as substances, gambling, sex, etc.

Addiction is just a symptom of the disconnect.

The brazen "war of drugs" has instilled in us a mentality in which we vilify those who struggle with addiction. It's easy for those more fortunate to point fingers and say "you don't belong" and it's shaped our society to write them off as "lazy", "indulgent", and "unworthy" of help. We literally throw people in cages for struggling with a larger issue of separation and we hate them when they are unable to recover, thus perpetuating the cycle of social displacement/addiction.

I was convicted to write about this because I feel like with the recent passing of artists this year like Mac Miller and Lil Peep, our society is so quick to write these incredibly talented artists off as just another rapper who partied too hard or that all they cared about was living in the moment. Nobody stops and thinks to wonder exactly how these individuals realized they were in a cage.

I believe it's our generation's responsibility to rehabilitate how we perceive addiction and why we feel a disconnect sometimes. Understanding our need to socialize and discovering the depths of our own humanity isn't a weakness, and we need to do a better job of making sure that those who think they're alone in the ring, have good people in their corner.

So check on your peoples, man. Share a connection. Form a bond. Rediscover what it means to be human.

The opposite of addiction is not sobriety; the opposite of addiction is connection.

- Johann Hari