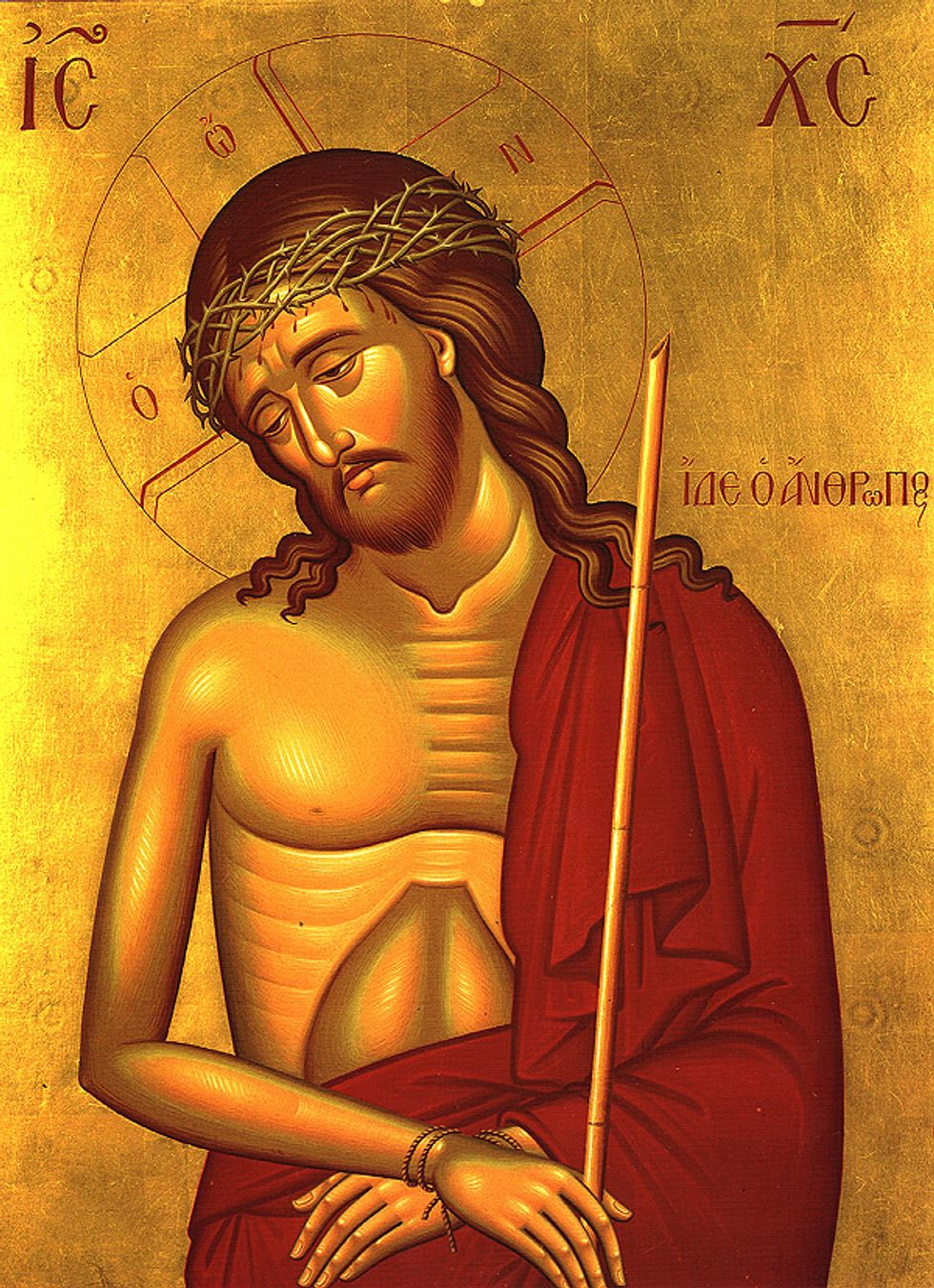

Holy Week is upon us. Having been physically weakened by forty days of prayer and fasting, we have finally arrived at the climax of the year and have the privilege of stepping through the last week of Jesus’ life with Him. We get to be there with Him as He triumphantly rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, praised by the crowds quoting from the Psalms. We get to be there with Him and His disciples as they partake of the Last Supper in the upper room. We get to struggle to stay awake with Him as He prays in agony, awaiting His betrayal by Judas Iscariot. We get to watch as He is tried by Pilot, convicted, and sentenced to crucifixion. We watch as He gives Himself up for the life of the world. We see Him give up His spirit. And we await His resurrection on the third day, perhaps doubting that it will happen at all, but still awaiting the joy that comes with seeing the Lord again.

What exactly is the meaning of all this? Why does the Church insist that we step through the life of Christ moment by moment, including the suffering, crucifixion, and shame of it all? Part of the answer deals with the fundamental nature of the gospel. For Christ Himself says:

“If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me. 24 For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake, he will save it. 25 For what does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses or forfeits himself? 26 For whoever is ashamed of me and of my words, of him will the Son of man be ashamed when he comes in his glory and the glory of the Father and of the holy angels. (Luke 9:23-26).

Thus we realize that this suffering and self-denial is needed in order for us to be able to accept Christ moment by moment. If we do not deny and say no to ourselves, there will not be enough room in our lives for Christ to come and dwell within us. But how do we deny ourselves? How do we keep this attitude in our hearts and minds every moment of every day?

I believe that part of the solution in continually doing this lies in the nature of time. In Eugene Vodolazkin’s novel Laurus, a Roman Catholic who receives visions of the future from God comments about the nature of time while talking to a Russian man who is devoutly Orthodox. He says:

I am going to tell you something strange. It seems ever more to me that there is no time. Everything on earth exists outside of time, otherwise how could I know about the future that has not occurred? I think time is given to us by the grace of God so we will not get mixed up, because a person’s consciousness cannot take in all events at once. We are locked up in time because of our weakness.

Thus, according to Vodolazkin, the solution to this lack of attention in our spiritual lives is to be brought beyond time and into the realm of God, which is fundamentally outside of time. And this is precisely what Holy Week does for us. It is not only a remembrance of past events that happened in the last week of Christ, but is rather a joining of the present back to the last moments of Christ which transcends space and time. In a very real sense, when we receive the Eucharist in the Divine Liturgy, we are present with Christ and His disciples in the upper room. The past comes rushing forward to the present, and the present is eternally linked to the past in order to bring Christ’s body and blood to us that we may have Him indwelling in our hearts and minds. It is for this reason that the Church sings, “Today has salvation come to pass in the world. Let us sing to Him who resurrected from the tomb and is the Author of our life…” Our salvation is not at some moment in the past, present, or future. It is a present reality that is continually ongoing, woven into the very nature of time itself.

Let us thus go and follow Christ, that we may die with Him. It will be painful, but we will also be raised with Him in His glory, singing, “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and on those in the tombs bestowing life.”

mr and mrs potato head

StableDiffusion

mr and mrs potato head

StableDiffusion