At Duke we strive to “develop our resources” and “increase our wisdom.” So we study, and we read, and we live, and we dream, and we hope. “We” are in this together; “our” resources and wisdom are cultivated and in pursuit of high ethical standards, professional aspirations, and intellectual growth: we become, for better or for worse, an educated elite. Duke degrees brand us: we are recipients, practitioners, or ancillary actors performing in the drama of Duke University’s “superior liberal education.” At an academic institution like Duke, we become the “real” leaders in our communities. We are the protagonists, the showstoppers—all eyes are on us, so we imagine, as we’re given props, a stage, and most importantly a script to follow.

I’ve realized our audience is only ourselves—each other—our Facebook friends, our floor mates, or our professors. Our script tells us that we’re the cream of the crop. We are righteous; we are the real leaders of tomorrow. But quite frankly, I’m not convinced of this. I’m no leader right now, I’m no showstopper, and neither are the majority of my peers. Especially after this election, we’re the one’s being led.

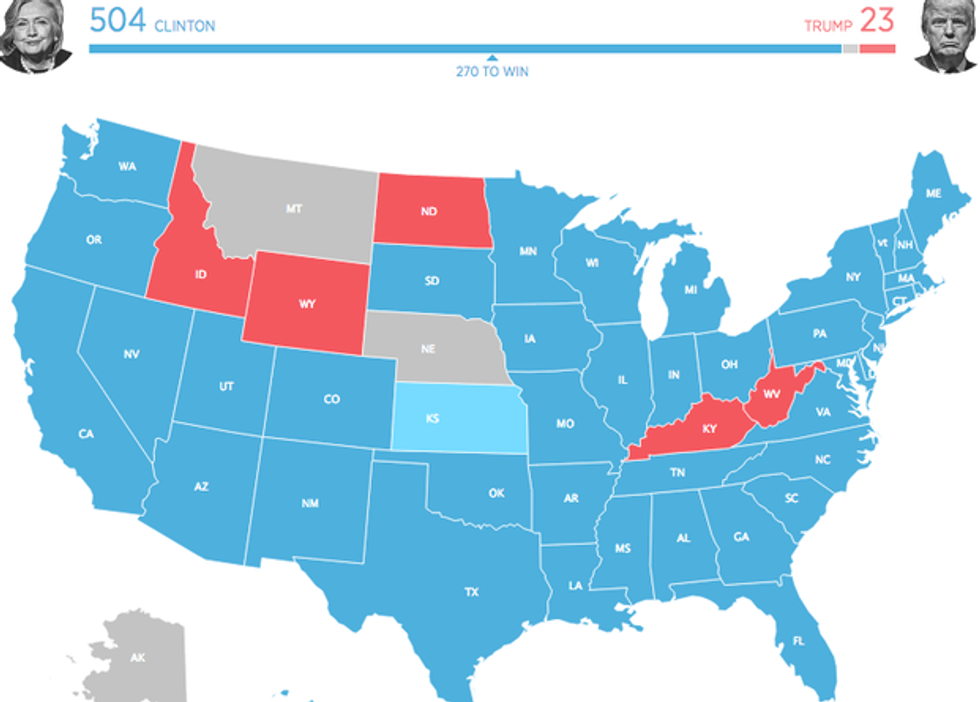

James B. Duke, I’m sorry to inform you that our newly elected national leader does not have a Duke degree. And I’m also sorry to inform you that the populations that overwhelmingly lead his crusade toward the White House were not Duke students—predominantly not even college graduates. Generally speaking, these voters were displaced white workers whose hope of the ever-elusive American Dream had vanished. Van Jones called this the “white lash.” And yes, a white lash it is; however, Charles Camosy noted a more startling revelation:

“The most important divide in this election was not between whites and non-whites. It was between those who are often referred to as “educated” voters and those who are described as “working class” voters.”

Tending to the development of our own intellect and economic, social, personal, spiritual, and emotional resources, I fear and know that Camosy is right—we’ve neglected the communities that Duke’s mission statement has so boldly encouraged us to lead. Yes, a large component of education is self-serving. But as Duke’s mission statement suggests, a “deep appreciation” for “human difference” and a sense of the “obligations and rewards citizenship” are our other-serving objectives. Unfortunately, I’ve only felt disconnected from deep human difference here. Duke has bodily and spiritual and cultural and racial diversity, but when it comes to intellectual diversity, among millennials at a place like Duke and many other elite institutions, the vote was as blue as can be.

This election of Donald Trump brings to light the crisis of a national humanities curriculum. Camosy argues that academic institutions suffer from a lack of intellectual diversity—ideologies, not just bodies and demographics, are underrepresented. An overwhelmingly blue vote does not necessarily affirm that there exists little or no ideological diversity—the distinction is that there exists an inordinate divide between the psychic landscapes of voters. However, bringing in bodies with different ideas would not be a solution; partially because there might not be a large enough population of college aged students with other polarized ideologies. The pressure then falls on the shoulders of intellectual communities like Duke; moreover, the pressure falls upon the shoulders of the humanities classroom. Camosy claims that people are fail to recognize the theological and philosophical considerations that motivate working class voters, considerations which are rather alien to most insulated, secular institutions like Duke.

Duke cannot be a place of escape or of societal divide from groups we are striving to “deeply appreciate.” Higher education must encourage students to not only deeply appreciate human difference but to deeply understand human difference. So far, my Duke education has treated Trump voters like a fine wine. Take a swig, swirl the glass, sip it, smell it, scrutinize it, and state your ever-so-righteous estimation. (The Chronicle anyone?) I’ve tasted, but I haven’t seen. I’m placing the burden on the humanities because this is where we can investigate the primary sources that feed and inspire our world views—be that utilitarianism, the Talmud, or reality television—I need to know more than just multivariable calculus and supply and demand curves to understand the prejudice and pain of our nation. If we’re truly called to be leaders of this world, we cannot disregard the necessity of the humanities. This is about humanity, not just our own humanness. As a student, I’m reminded: my education is not just about my interests, my future—not just about me.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion