Underdog stories, while ingratiatingly clichéd, are universally beloved. Didn't we all shed a tear when Rudy was carried off of the field, and nod drowsily in church when David defeated Goliath? But while an underdog can elicit universal cheers (or, at worst, mild applause), some shine dazzlingly, stun the world, and are summarily relegated to obscurity. Helen Gurley Brown is one such figure.

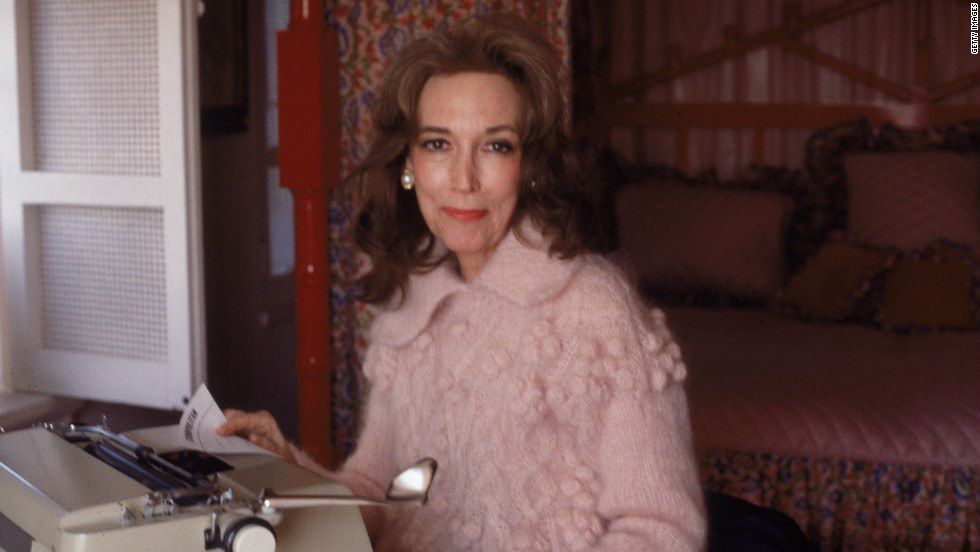

Brown, the author of 1962's highly controversial, "Sex and the Single Girl" (in which she dismantled the stigmatization of women having premarital sex), became the editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan in 1965, a position she would hold for over three decades. Proudly waving the banner of sex, Brown revitalized the failing magazine and drew the ire of feminists everywhere due to what they felt was her tendency to objectify women through her invention of the "Cosmo Girl," the female counterpart to the consummate bachelor for which Playboy was written.

To those in literary, feminist, feminist literary and literary feminist circles, the legacy of Helen Gurley Brown is almost exaggeratedly divisive. One on hand, she was a woman who encouraged women to rise in the workplace, to play the patriarchal system to their advantage by using sex as a weapon, of course, and establish their financial and personal independence. On the other, her focus on sex was viewed in the eyes of feminists, such as Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan, as a means to subjugate women and reinforce oppressive standards of beauty and femininity. The only thing that can be agreed upon by her admirers and detractors is that Helen Gurley Brown, the self-proclaimed "mouseburger" from Little Rock, was an unendingly contradictory and complex persona.

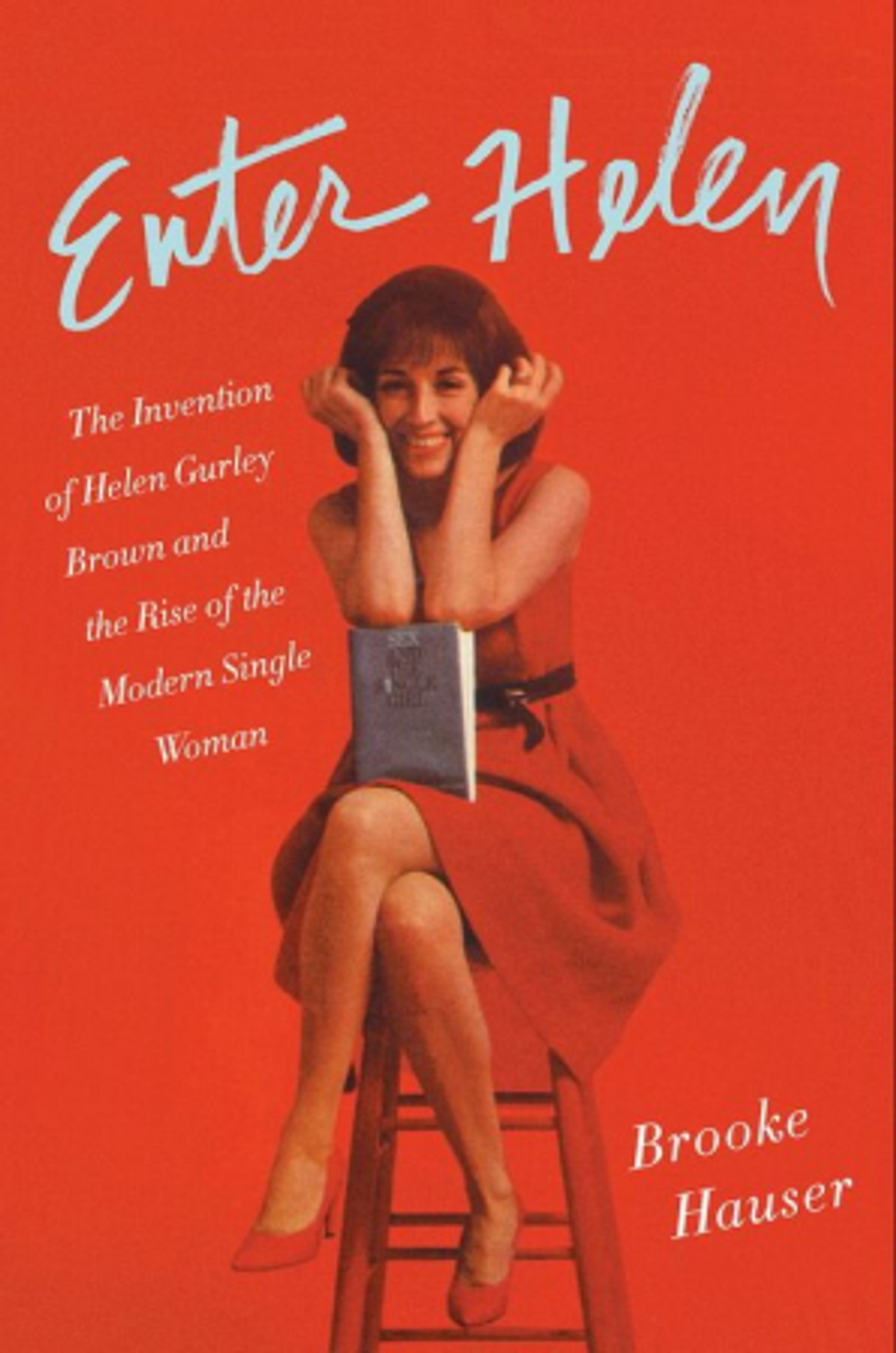

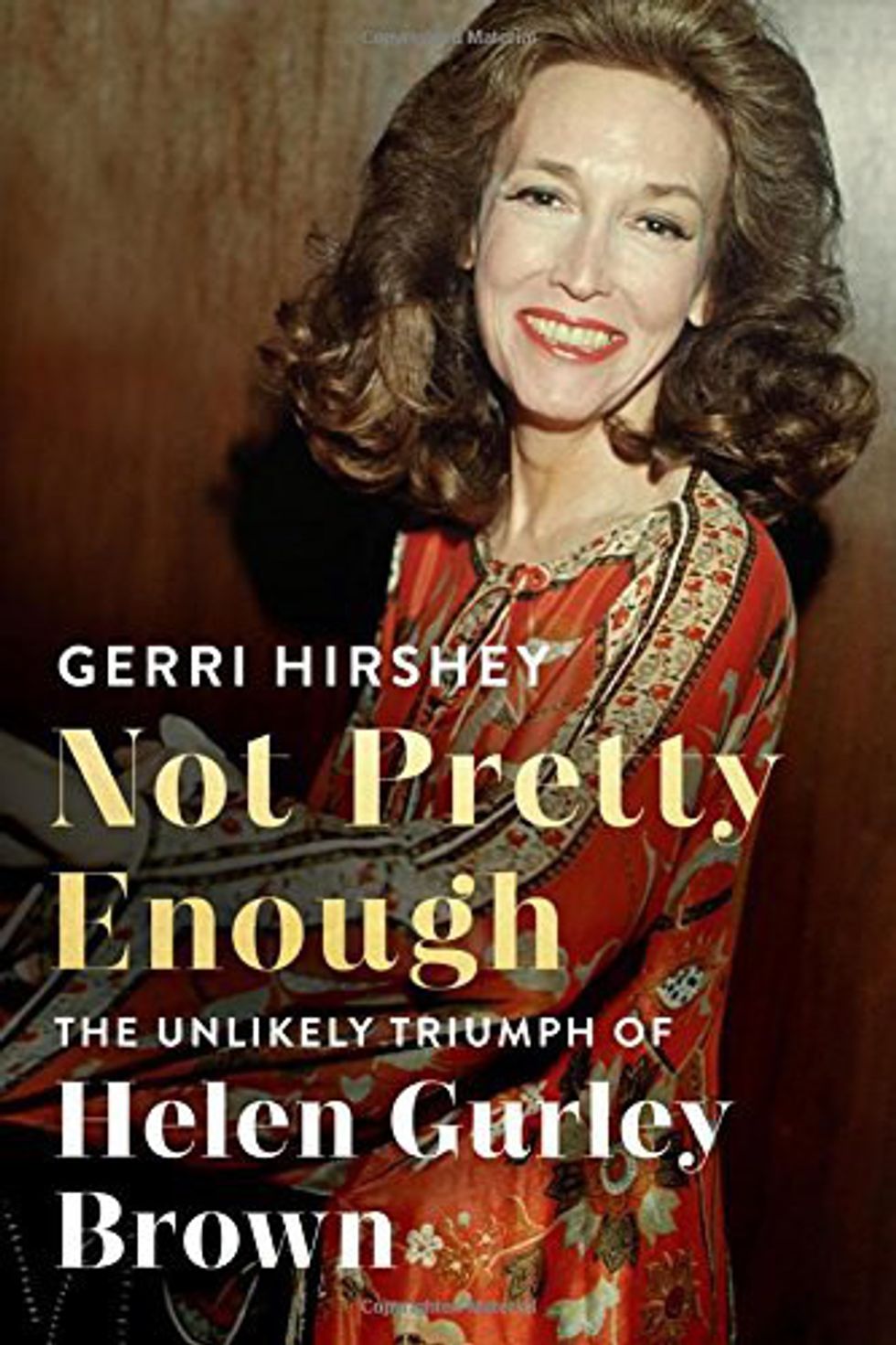

In the four years since her death, Brown and her impressive résumé have been all but buried by a cruel combination of the onslaught of time and the public's increasingly short attention span. This year, however, authors Gerri Hirshey and Brooke Hauser have dredged the fascinating story of Brown and her pioneering efforts in sexual advocacy up from antiquity and presented it in two vastly different biographies; "Not Pretty Enough: The Unlikely Triumph of Helen Gurley Brown" and "Enter Helen: The Invention of Helen Gurley Brown and the Rise of the Modern Single Woman," respectively. The books both tell of the fascinating victory of a driven woman against insurmountable odds and her monumental impact on American society through, what else, the sexual revolution and Cosmopolitan's role in it.

Hauser's biography is tantalizingly colorful and deceptively thick. While she presents the full story of Brown's ascendency to power and pop-culture iconography, it is done so in an overly-palatable format that makes for an all-too-breezy summer read. With chapters rarely exceeding five pages in length and an uneven chronology which, while easy to follow, seems jumbled and awkwardly situated, "Enter Helen" verges on reductive.

Hirshey, to an extent, picks up where Hauser leaves off, going into almost excessive detail while tracing Brown's family history and offering greater insight into the tragic childhood which shaped and scarred HGB and the misogynistic workplace slights which propelled her toward unprecedented success. While by no means an arduous read (aside from a few bits and pieces which should have been omitted), it still approaches the subject with vastly more vivid detail.

Unfortunately, both books -- despite the rich story found within -- fail to answer the glaringly obvious question of why four years after Brown's death and roughly 40 years after her heyday, these two biographies are worth writing, much less reading. While her interactions with powerful, society-altering women such as Nora Ephron, Betty Friedan, Joan Rivers, Gloria Steinem, Jacqueline Susann, and Joan Didion are detailed across both tomes, Brown's influence on modern feminism, while palpable and even hinted at, is very obviously absent. This omission is, in a sense, vastly more telling than anything written; Brown's heavy-handed, bold and aggressive -- yet stereotypically feminine -- imprint on the worlds of publishing, activism and feminism is perhaps too antithetical to explain; perhaps Brown -- who refused to let her carefully curated defenses down and reveal her true self to the public, motivations, regrets, and all -- would prefer it that way. Then again, she might have refuted the idea of this unanswerable question regarding her life's work with her signature dismissal, "Aw, pippy poo."

The two biographies read best in tandem, with both sharing a sapid style of writing that demands little of the reader. And while those interested in this fascinating-in-the-extreme figure should begin with Hauser's "Enter Helen" and end with Hirshey's "Not Pretty Enough," a clear, discerning portrait of the enigmatic Helen Gurley Brown should not be expected.

For an informative, untaxing read, "Enter Helen" both educates and entertains. For a more insightful piece, "Not Pretty Enough" is superior, though mired in minutiae. Whether you choose one or the other, or both, be sure to pay careful attention as anyone -- male or female -- can glean useful lessons from HGB, especially in the way of her most dreaded pitfall, "Not sexy enough!"