“I strive to be a part of the solution. I see and understand how order is needed in the world and in our individual lives. My experiences have granted me knowledge of how to create art and how to see beauty in everything that exists." -- Tyree Guyton

---

Tyree Guyton, the artist who created Detroit’s world-famous Heidelberg Project, has revealed in an interview that he plans on dismantling the project over the next two years, with the goal of transforming it into a larger-scale arts-infused community project.

Heidelberg 3.0, or so it will be called, will be a positive change for the community, according to Guyton. “After 30 years, I’ve decided to take it apart piece-by-piece in a very methodical way, creating new realities as it comes apart.”

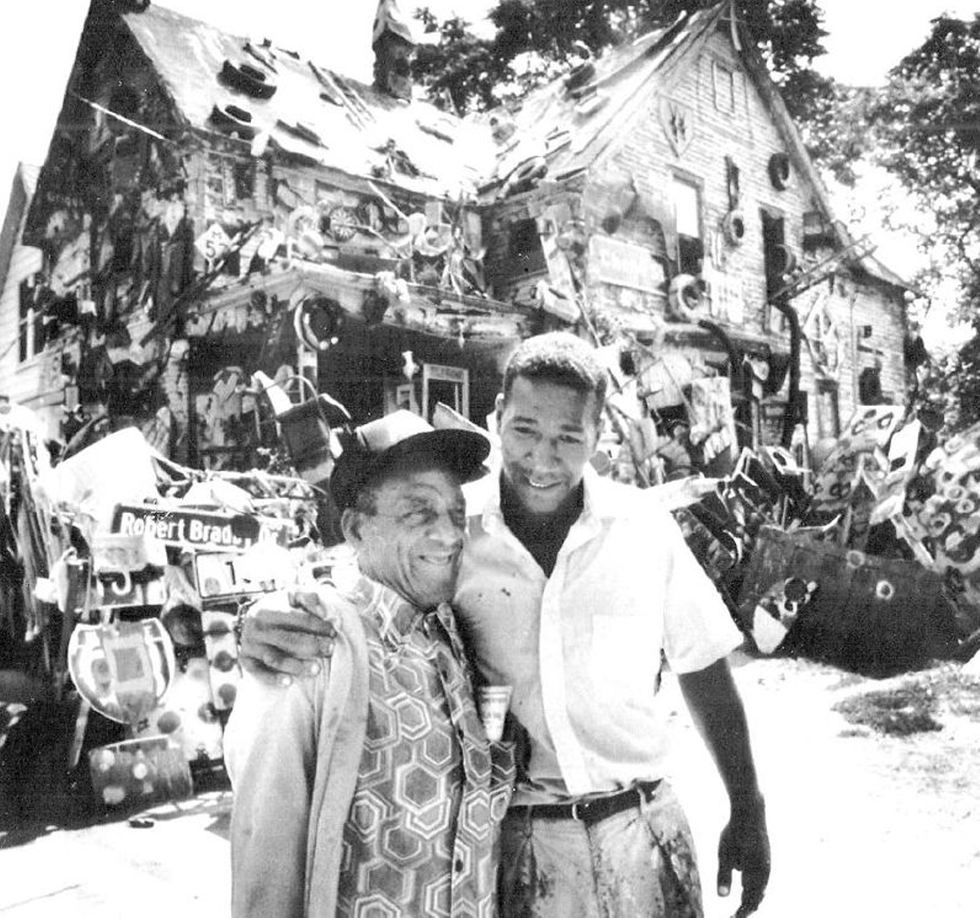

Guyton and his grandfather, Sam Mackey, started the Heidelberg Project in 1986. After serving in the army, Guyton came back to his home in Detroit and was astonished to see that urban decline his neighborhood had faced, saying that it looked like “a bomb went off.” The project is in part a political protest in response to the deterioration that began after the 1967 riots, during which the area suffered a great population loss and business losses. Areas that had once thrived with Black-owned businesses were being abandoned.

This is where the Heidelberg Project started. Guyton and Mackey took the depilated structures and began revitalizing them with bright colors and patterns in an effort for creative exploration and artistic rebirth. The neighborhood entirely transformed. Empty houses became bright with painted polka dots and patterns; scenes were set with additions of artifacts such as toys, clocks, TV sets, signs, shoes, and anything else that could be found.

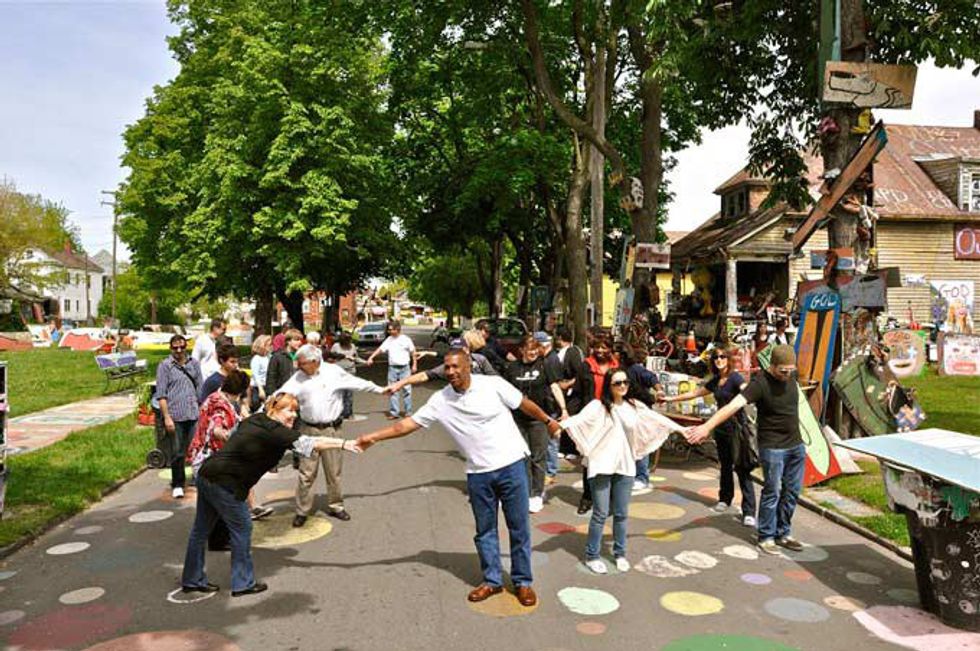

The idea was to bring people together, to create a community filled with art and life. For many, this is exactly what it was, bringing beauty and spunk to the then-bleak Detroit.

Not everyone has felt that way, however, and the project has been met with a plethora of criticism over the years.

Then-Mayor Coleman A. Young was one of these criticizers, and consistently proclaimed that the houses weren’t art and pushed plans to take it down under the claim that it interfered with urban planning initiatives. Under his term, three houses on the street were completely demolished, including “The Baby Doll House,” “Fun House,” and “Truck Stop.” In 1999, under Mayor Dennis Archer, three more houses were destroyed, including “Your World,” “Happy Feet,” and “The Canfield House.”

In addition to this, the project has survived countless attempts to seize properties by the city and 12 fires, all deemed suspicious but with no arrests to date.

All of these setbacks, however, caught national attention. Magazines took notice and wrote articles calling the work fresh and vital, and galleries have invited Guyton to showcase his work. The fires and attacks on all the works even garnered an online effort to raise funds for extra security at the site – raising $50,000 by the end of it. The nonprofit even challenged the city’s efforts to dismantle the sites and won an appeal for eight of the effected properties.

Now, though, after 30 years in international attention, the project will be taken down and reinvented. Says Guyton, “I gotta go in a new direction. I gotta do something I’ve not done before.”

Dan Lijana, spokesperson for Heidelberg, says that there will “always be a footprint of the project, just not as people have known over the years.” The commitment of the community to the project has always been profound, with volunteers coming in to take care of the sites, offering their talents to spruce up the area, coming and adding materials to the sites, protecting it, and inviting visitors from around the world to come and partake in the Heidelberg experience.

“I’m on an elevator, and I’ve taken it from the ground floor up to the very top 30 years later. Now I’m reversing that process, and I’m going to take this elevator down.” Guyton continued, “I’m gonna stop on every floor to look around and see the beauty of taking it apart, and do it in a methodical way, where it becomes a new form of art.”

Dismantling the project is only just the beginning, and is a beginning in and of itself. Over the next two years, the objects placed on the streets of Heidelberg will be gone; some are expected to be donated to museums across the country to memorialize the project, while others will be sold to raise funds for future efforts.

The four houses that have survived the decades will remain. The “Dotty Wotty House” is expected to become a small-scale museum to celebrate the effects Heidelberg had on its surrounding community and the art world.

There will also be a fundraising campaign, led by Jenenne Whitfield, the executive director of the project (and Guyton’s wife), to secure the future of the project and begin its metamorphosis, as well as provide a retirement fund for Guyton.

"It was time to put the clocks out here in such a way that I could see them every day, and you become what you see, what you talk about, what you do," Guyton said. "And a chance to share with the world that I'm exploring and playing with time. If I die tomorrow, I've fulfilled my purpose."

---

For more information about the project, its transformation, and how you can be part of it, check out their website at: www.heidelberg.org