In my study of anthropology, I became aware of how cultures can often be at odds. In "A Heart for the Work", Claire Wendland highlights the great disparity between health care in the Global North (first world countries) and health care in the Global South (developing countries) as she studies the medical world of Malawi. However, as I have sought out stories and read more, I have come to believe that globalization is not always about conflict because in some areas the struggles are common.

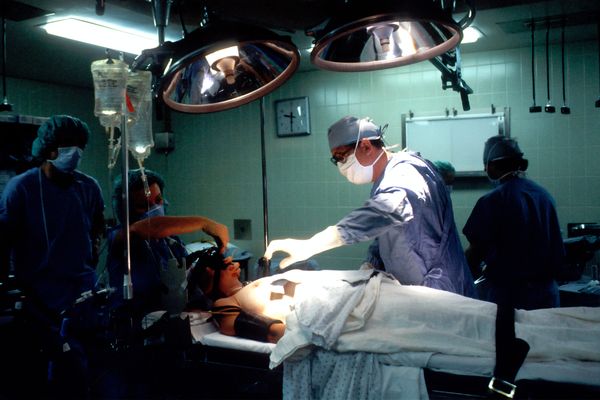

Biomedicine can be defined as a branch of medicine which applies physiological and biological principles into clinical practice. We think of biomedicine as universally helpful. However, the difficulty in implementing it successfully throughout the world is partly due to what Paul Farmer says, that “there isn’t enough of it to go around.” There is also a resistance among the recipients. The force behind this resistance, I find, does not simply come from the challenges which foreign cultures pose for doctors. It also comes from apprehensions about unknown medical procedures, mistrust of the motives of politicians who promote health care at home and abroad, and the absence of supportive laws. Preventative health care, therefore involves social awareness and social activism and these are important issues, not just for any one culture, but worldwide.

"A Heart for the Work" follows a cohort of medical students in Malawai, the distinctive paths which brought them to medical college, and their “realization stories” in which they describe how they came to be who they are. Malawi had an environment where diseases like Malaria were just as common as “witchcraft –related illnesses.” With a paucity of resources, all that doctors could often do was to slap “inadequate bandages over the deep wounds of inequality.”

The student doctors were trained in modern biomedicine, but frustrated by the “abstract presence and material absence” of equipment and medicines. Perceptions about their own competence become apparent when Wendland describes how they looked up to visiting students from Europe or the United States. Nearly a third of the comments made about these “medical tourists,” says Wendell, had to do with the “relative riches -- both in equipment and opportunity -- available to the tourists.” The locals were envious of the reflex hammers, pocket medical guides and tools like blood pressure cuffs which bulged out of their pockets and which symbolized the high status of “Northern students.” They had witnessed Swann-Ganz catheters and laparoscopic procedures which the Malawians had only read about. It made them think of Malawian medicine as second-rate.

What is interesting for me is how all this affected some of the students in their aspirations. Mkume was certain that clinical practice would not suffice for him. As a child, he used to go with his father to the village, where they would help people by providing necessities like groceries. These would only last a few weeks. This influenced Mkume to become a doctor mainly because he wanted to give them “something which would last longer than two weeks.” He had a vision for how he could best serve his country. The Global North represents economically developed societies such as Europe and North America whereas the Global South refers to economically developing countries such as Africa, India, China, Brazil and Mexico. Wendland describes how health care in the Global North tends to perceive the world in a certain way and the practice of medicine is designed to fit this model. However, Mkume acknowledges that we are all a part of the same “big mess.” Medicine has to transcend the number of medical supplies you have. You can only do so much with medical kits and technologies. It is about seeing the needs of others and working towards helping them. That is the most important thing. Doctors should be those, as Mkume expressed, that you can look up to help not just medically but psychologically and spiritually as well.

Most of what Mkume expected to do was preventative medicine, in particular for HIV and TB. In a sense, he was focusing on the concept that while medicines can often heal one sick person over a period of two weeks, preventative medicine affects a larger population and reduces the number of those who fall prey to illnesses.

I refer to what I mentioned earlier regarding social awareness and social activism being important issues for medicine, not just in what Wendland would call “the Global South,” but worldwide. Barbara Barlow, MD, is an advocate of “Injuries are not Accidents.” She is Director of Surgery at Columbia University and Director of Injury Free Coalition for Kids. Barlow initially found that pediatricians were the only ones who understood that preventing injuries was all important. According to Barlow, pediatricians are in the profession of preventative medicine. They strive to protect children from infectious diseases, while surgeons make a living from fixing injuries.

Appointed to a hospital in Harlem, Barlow was inspired to find a way to improve the lives of the children in a community struggling with poverty and crime. Her initiative took the form of “Children Can't Fly”, a program for placing window guards in high rise residences. She also started The Harlem Hospital Injury Prevention Program, which coordinated the efforts of physicians and community, with the aim of providing safety education and safe activities for children. Incidents of injury were greatly reduced, and the program was replicated in many cities.

Barlow’s dedication and passion proved what Wendland’s book aspires to communicate. Despite all the odds, the students and doctors did what they could to help their patients. Like Mkume, Barlow’s desire came from the heart and fueled a vision to create healthier communities. Working from the “heart” can make all the difference.

Medicine, as Wendland describes, has a moral economy. It has a set of values related to being universally beneficial, but these values must be applied in variable economic situations. This essentially means we must accept that the implementation of biomedicine cannot stray from culture. Yet it is not strictly a case of Western versus Eastern culture. Preventative medicine is a common goal for the world. It requires communication among all stakeholders, be they doctors, patients, hospitals, governments, donor agencies, or community members. It is this communication which will help us transcend cultural differences. Medical anthropologists can play a vital role in connecting the stories of those who have championed the cause of preventative medicine. Collectively, their stories will demonstrate that education, social awareness and social activism can lay the foundations for the global implementation of modern medicine everywhere in the world. What we need is a heart for global medicine.