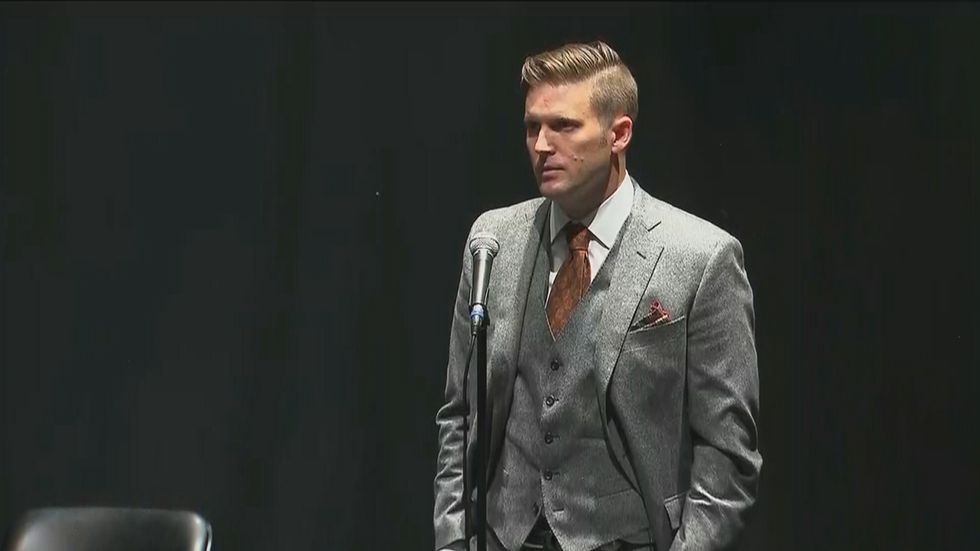

Last August, Chancellor Folt sent us an email announcing that alt-righter Richard Spencer wouldn’t be allowed to come and speak on campus. Her reasoning: “Our basis for this decision is the safety and security of the campus community.”

Williams College did a similar thing in 2016, its president, Adam Falk, somehow coming to the conclusion that allowing a speaker was the same as promoting said speaker. UNC refused to cancel just such a controversial speech in 2009, and the speaker was driven from the room by protest. You’ve all heard about UC Berkeley.

These are just a few scattered examples: I’d be repeating the most worn-out cliché if I were to say that college campuses are increasingly against freedom of speech. I’m not going to add to the humongous pool of internet diatribes against said phenomenon. But I think it’ll be helpful for all of us to work toward an explanation of why colleges are against free speech.

First and foremost, it seems, is the dominant and barely-questioned idea that speech can be violent. It can’t. That question, though, deserves a second article: It will be published about the same time as this one. If you can’t find it, let me know and I’ll shoot you a link.

No, the more interesting reasons are that we’ve actually lost touch with time and modality. I’ll come back to the whole “modality” thing later, but for now, let’s figure out time.

It’s like some sci-fi shit: The aforementioned email from Chancellor Folt cites “safety” as the reason Spencer wouldn’t speak at UNC. As we already know that speech can’t be violent, she’s counting on violence resulting from his speech. And maybe she’s right: the Charlottesville protests set a scary precedent.

Her rhetoric, though, is scarier. Free speech is never taken away without reason: Every unjust censor and every totalitarian regime you’ve ever heard of has trashed free speech in the name of safety.

Folt’s trying to incite fear: terrible things, she says, could happen if we allow non-mainstream ideas to be heard.

So by pretending to be prescient, Folt fuses a fearmongering vision of the future to the prospect of hearing new ideas in the present. This is irrational, but people eat that shit up.

Now, what about modality? First, to define it: Some verbs are actions on their own. Others focus on our moods about those actions: they state whether things should be done, whether they could be, and whether they’re allowed to be. Those mood-altering verbs--would, could, can, etc.--are modal verbs.

And when people like Adam Falk, president of Williams College, refuse to allow campus groups to host controversial speakers because the college won’t “promote” such speakers, those people are ignorant of how modality works.

We can agree that the particular speaker disinvited by Falk was a first-rate dickhead. But Falk has lost sight of the difference between can and should. To allow someone to speak is not at all the same as endorsing what they say. To allow someone to speak is to allow them to be disagreed with, to allow their ideas the potential to be shot down, or at the very least to allow your side the advantage of knowing its enemy.

So Falk’s claim that alt-right speakers have “little or nothing interesting to say about critical issues” is as terrifying as Folt’s fearmongering: By restricting the realm of “critical issues” only to those things seen as important by declining establishment politics, Falk is ignoring the blatant fact that the alt-right is a legitimate political force which now has some part in defining what critical issues are.

As I said in my article on art, the kind of narrow vision that Folt and Falk both promote is exactly why neofascists have been able to seize so much power around the globe so quickly: They’re widely ignored by those who condescendingly consider their views unworthy of opposition. And so who knows how to oppose them?

To try to stifle the new conservative line of thinking, so often called “hate speech” or “violent rhetoric,” will only lead to being silently conquered by it.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion