In my ASL class, we watched a very powerfully emotional film called Hear and Now, a 2007 HBO documentary. The film is about an elderly deaf couple, Paul and Sally Taylor, getting a cochlear implant. The film is written, narrated, and directed by their hearing daughter, Irene Taylor Brodsky (director of Beware the Slenderman and Open Your Eyes). The film depicts the couple’s journey before and after getting implanted.

Early on in the film, the narrator discusses her parents’ time as school students. At school, they practiced oralism rather than American Sign Language. This was at a time when schools did not want deaf children learning ASL because they believed that they would not adjust to communicating with English-speaking hearing individuals. Nevertheless, Paul and Sally both spoke English and used ASL as senior citizens. Last year in ASL 1, we watched another documentary that brought up this point called Through Deaf Eyes. In that film, deaf students’ hands were tied as a punishment for signing. To get back on point, it was very hard for Paul and Sally to learn how to speak. The narrator mentioned that it took a long time just to learn how to speak one word. In addition, they learned to make lipreading a valuable skill. The daughter states in the beginning of the film that the parents communicate with her and her siblings through lipreading. My professor, Carol Kearney, said in ASL 1 that deaf people are very good at reading lips.

As for Paul and Sally’s implantation, graphic footage of the surgery was shown. Most of the students in the class, including me, had to cover their eyes.

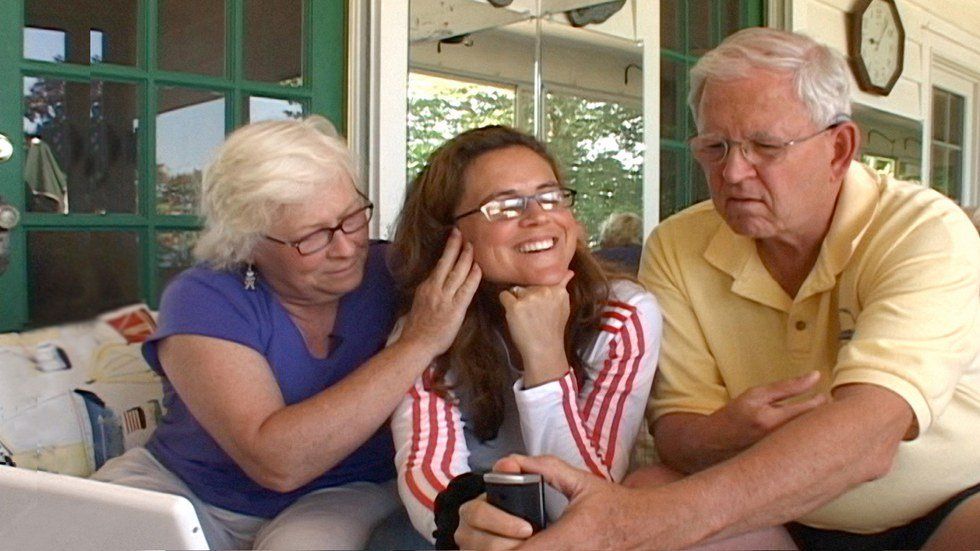

What I liked a lot about this documentary is that it illustrated how although the cochlear implant can improve deaf people’s hearing, it not a magical cure for deafness. Interestingly enough, the narrator mentions that the doctor told her parents not to turn their implants on right away being that they had to wait for the swelling to go down. More importantly, she also mentioned that the doctor warned her parents not to expect too much so soon. After turning on the implant, Paul and Sally went through a “honeymoon phase.” Sally cried tears of joy after hearing for the first time. Paul drove his car twice a day to the car wash. The narrator describes this as her father “acting like a kid at a candy store.”

In spite of these firsthand reactions, the bliss over the implant did not last for too long, especially for Sally. After all, although Sally could hear voices, she could not differentiate between them right away. 6 months after getting the implant, Paul and Sally went to the audiologist for a checkup on their hearing progress. The audiologist tested them by covering his mouth with an object, saying words, and waiting for them to repeat those words. Although Paul and Sally could hear the audiologist, they could not understand everything he was saying, especially since they were not allowed to lipread. They could not repeat back words. Sally also went through a pattern where she could hear in the morning, but not hear as well during the afternoon and nighttime. There were also times where too much sound overwhelmed Sally and gave her a headache. This comes to show how too much sound can be very overwhelming for newly implanted deaf individuals. Additionally, the film stresses how not only can too much sound too soon be overwhelming for the deaf individual but the cochlear implant as well. For example, when Sally went grocery shopping, she put the volume on maximum. Consequently, she could not hear. The same situation occurred on Christmas.

The most emotional part of the film for me was when Sally cried while saying, “The funny thing is after I got the C.I., I wanted more and I’m not getting it. I’ve been deaf for too long! Maybe if I had gotten the C.I. when I was young ..5...7...10, it would be great. But now? At 65. But I knew that before I had the surgery that would happen. Why it affects me now I don’t understand. I should expect it. But I’m not sorry I got the implant. Trying new things and seeing what I could get. Fine. But why wait until you’re 65 and then get one? It’s too late. I need 65 years more to learn how to communicate, and it’s not going to be possible.” Before Sally said this, the audiologist said, “We sometimes talk about ‘young brains’ and ‘old brains.’ Young brains in young children are very, very good to learn quickly. Older brains are set in their ways essentially and it takes a lot longer and you have limited success in re-teaching your brain how to hear, but that doesn’t it doesn’t re-learn. It just takes longer, and the results are more limited than what we’d expect in a young child.”

Nonetheless, Paul and Sally got bored of the implant very easily. As stated previously, too much sound distracted them. In one scene, Paul took off his implant so he could focus on reading the newspaper. Similarly, Sally liked to drive without the implant, and she put the implant in the disc compartment. While driving, Sally liked to put music on and put her arm by the window to feel the beat. Although she obviously could not hear, she still liked to feel the vibrations.

Overall, what was more important to Paul and Sally, in the long run, was not whether or not they could hear, but their marriage. As the narrator says at the beginning of the film, “I think there was one more reason Mom and Dad wanted this change. It was so obvious that none of us even talked about it. It turns out this experiment is more than just about hearing after a lifetime of silence. Just as they’ve done everything for the last 60 years, it’s about doing this together.” Paul and Sally loved the simplicity of just being together. They loved watching the water waves, being with their dogs, and talking calm, silent nature walks. Interestingly enough, the very last scene of the film shows Paul and Sally walking together without wearing their implants. That scene made me smile.