Harry Pace was an African American political activist, producer, writer, banker, and teacher amongst many jobs that crossed his career path. (ASCAP) Arguably his most notable endeavor was Black Swan Records, for which he was the founder and main driving force behind America’s most notable early independent record label. In his book Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music, historian David Suisman makes it clear that, “Black Swan Records was an audacious didactic project designed to harness the combined power of music and business in the cause of racial uplift and the fight for social justice” (208). This company made an effort to raise political awareness for African American performers and consumers alike as well as create change in a rigid record industry. This endeavor was as much as an experiment for W.E.B DuBois’s political movements, as he was a main board member for the company. Black Swan can be argued as the pinnacle of Harry Pace’s career and is strongly influenced by his early life choices and decisions.

Pace was a protégé of W.E.B. DuBois. It is DuBois’s early influence in Pace’s life that would forever guide his future. It would be interesting to theorize what different set of events may have taken place had the two not crossed paths. Even after the company had been sold, Pace continued in fields where he could stay politically active and help push for better conditions in the lives of African Americans. Only a letter away, DuBois was kept in the loop throughout Pace’s life.

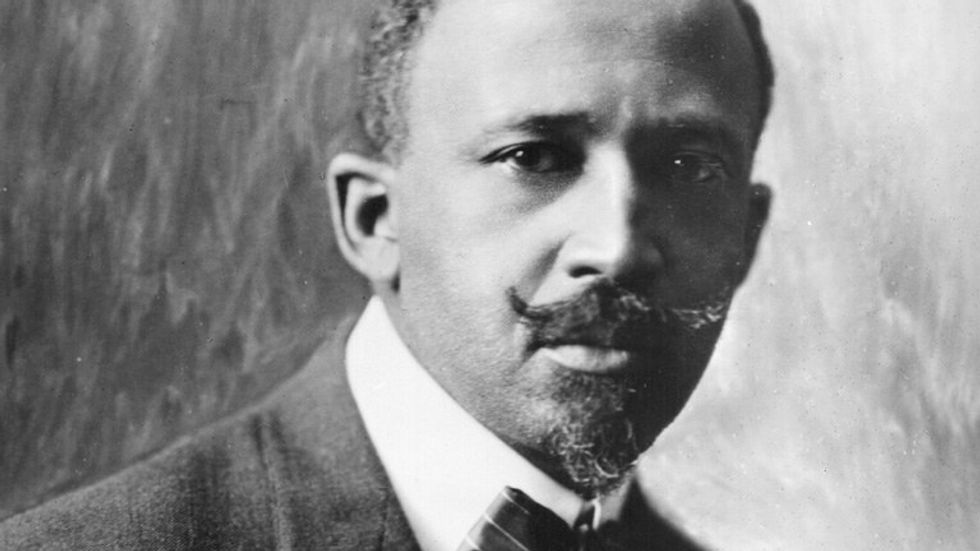

Before Harry Pace, or even the notion of a record company, it is important to take note the background and role of W.E.B. Dubois. Dubois, a Massachusetts native, was one of the most educated men working in social and political movements in the early 20th century US. He attended and received degrees from multiple schools, including Fisk and Harvard. His most famous credit is being one of the primary founders and driving forces of the NAACP. The majority of Dubois’s life and career was spent on the subject of race. He worked to help advance positive change for all African Americans and sought to bring equal treatment for them as well. I would like to look at two distinct ideologies that DuBois expressed which make a clear argument for why he would hold any interest in Black Swan Records, or Harry Pace for that matter.

The first set of ideas comes from DuBois’s own work, 'The Souls of Black Folk'. This book covers many social and political issues that arose after the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. The Bureau of Freedmen is one topic that DuBois goes into length over. He describes all the ways that this government branch both helped and created setbacks for new freed folk. Immediately following the emancipation and the war, many people of great wealth and political power urged the government to take action and help all former-slaves adapt into society. While some small advancement was made, it was not an easy road. “[Freedmen] Bureau courts tended to become centers simply for punishing whites, while the regular civil courts tended to become solely institutions for perpetuating the slavery of blacks” (DuBois pg.21). Sadly, the conclusions drawn from this part of the book show that the effort given was half at best. The research from these Bureaus’ cases and actions would drive DuBois in his own work stating how African Americas should organize themselves and where people went wrong in the past in creating jobs and equality because of race. DuBois held interests in those who could create successful and meaningful business that brought with themselves economic uplift. Black Swan, among other causes and groups that Dubois was a part of, became a type of proving ground for new sociopolitical steps in battling the race war. The final chapter of DuBois’s book, The Souls of Black Folk, holds two very startling realizations going into the early 20th century: “Caricature has sought again to spoil the quaint beauty of the music, and has filled the air with many debased melodies which vulgar ears scarce know from the real. The silently growing assumption of this age is that the probation of races is past, and that the backward races of today are of proven inefficiency and not worth the saving. Such an assumption is the arrogance of peoples irreverent toward Time and ignorant of the deeds of men” (DuBois 157, 162).

Blatantly, DuBois is commenting on how Black culture was being used to sell music and was being done so in the worst ways possible. Without saying it directly, DuBois is talking about the wrongful portrayal of black people through blackface minstrel shows and record companies hiring songwriters who were writing fake songs in the “negro style.” By buying into these markets, people were perpetuating racist culture and allowing the hate from past generations to be buried behind a mask. Black Swan Records provided an opportunity to help guide an effort to change this use of caricature and blatant racism found throughout the budding music industry. It could be used as a double edged sword, bringing African American recording artists to anyone who wanted to hear them and providing a political platform to stand up to the larger record companies who were hiding racial prejudice from many consumers.

The second idea that DuBois held was the concept of The Talented Tenth:the idea that there is a large number of African Americans who went through a full education would help lead the rest of the race (Gates). This concept is rooted way before DuBois but his actions show how much he believed in this controversial issue.

DuBois took Harry Pace under his wing while Pace was still in college. Pace would graduate as a valedictorian and would work hand in hand with Dubois in his early career. Even as their paths grew apart, Pace kept in correspondence with DuBois up until his death. Pace was the physical embodiment of this concept. With education, and close guidance, he became a leading businessman and underground political worker. In his article 'Who Really Invented the ‘Talented Tenth,’ Henry Louis Gates clearly defines how divided this issue was among political leaders and those waging the war on racism. This ideology does not neglect the other people not in the ten percent; they too are still knowledgeable and valuable. The focus on the top ten is that they have so much potential to create social change within their fields (Gates). Harry Pace’s ambition and drive was part of this ten percent. Granted, he had connections in high places, but he worked with his connections and was always making and solidifying friendships, all in the name of progressive business.

Harry Pace’s career was never about fame or fortune. It was about social political activism. He achieved this through his work, clearly inspired by DuBois, and by creating in his own means when an option did not exist. Black Swan is at the epicenter of this: it would be short lived but its shockwaves in the music industry would leave lasting impressions.

Harry Pace had a very nurturing start as a young adult. He was a strong academic student, much like his advisor DuBois. I think DuBois saw a lot of potential in Pace and wanted to have someone who could help carry out his work. As soon as he graduated, Pace was offered a job as the manager of a magazine run by DuBois. This paper would evolve into The Crisis, one of DuBois’s most popular publications of the NAACP (“Kingdom of Culture”). In time Pace had moved on to a series of other jobs and academic affairs. Looking over his life, it is clear that the man could not sit still in one spot. In leading up to Black Swan, Pace and W.C. Handy formed their own publishing company in New York. W.C. Handy was a blues artist and pioneer of the genre. While in New York, their publishing company faced immeasurable racial prejudice. Record companies did not want to record African American artists who were performing “non-negro” music (“Selling Sounds” ch7). They found it absurd that that anyone would want to hear a black opera singer or a quartet play Bach.

This racial prejudice lit a fire inside Pace. Pace left his publishing company with W.C. Handy and decided to start his own record company. Black Swan consisted of a board of trustees, with DuBois being the most influential and famous of those involved in this experiment of a company. Pace went full throttle in his endeavors. As David Suisman notes in Selling Sounds: “Pace tried to make Black Swan records available wherever people might acquire them.” Pace spared no expense in using blatant advertising. These ads, many of which appeared in Crisis, encouraged people to support the company as a means to show the other large record companies that they weren’t in charge of every good artist (“Black Swan Rising”). Over the course of it’s career, Black Swan recorded just about all contemporary genres of western music, including many famous performers of the day including Ethel Waters. In four years, Black Swan went from a start up, and emerged into a household record name. Its short life span graced the company with roughly a million record sales (Black Swan Rising). I would argue that Pace achieved the goal of economic uplift represented by Black Swan. An African American run business was founded, recorded its own artists, and made a positive change in a rather locked community.

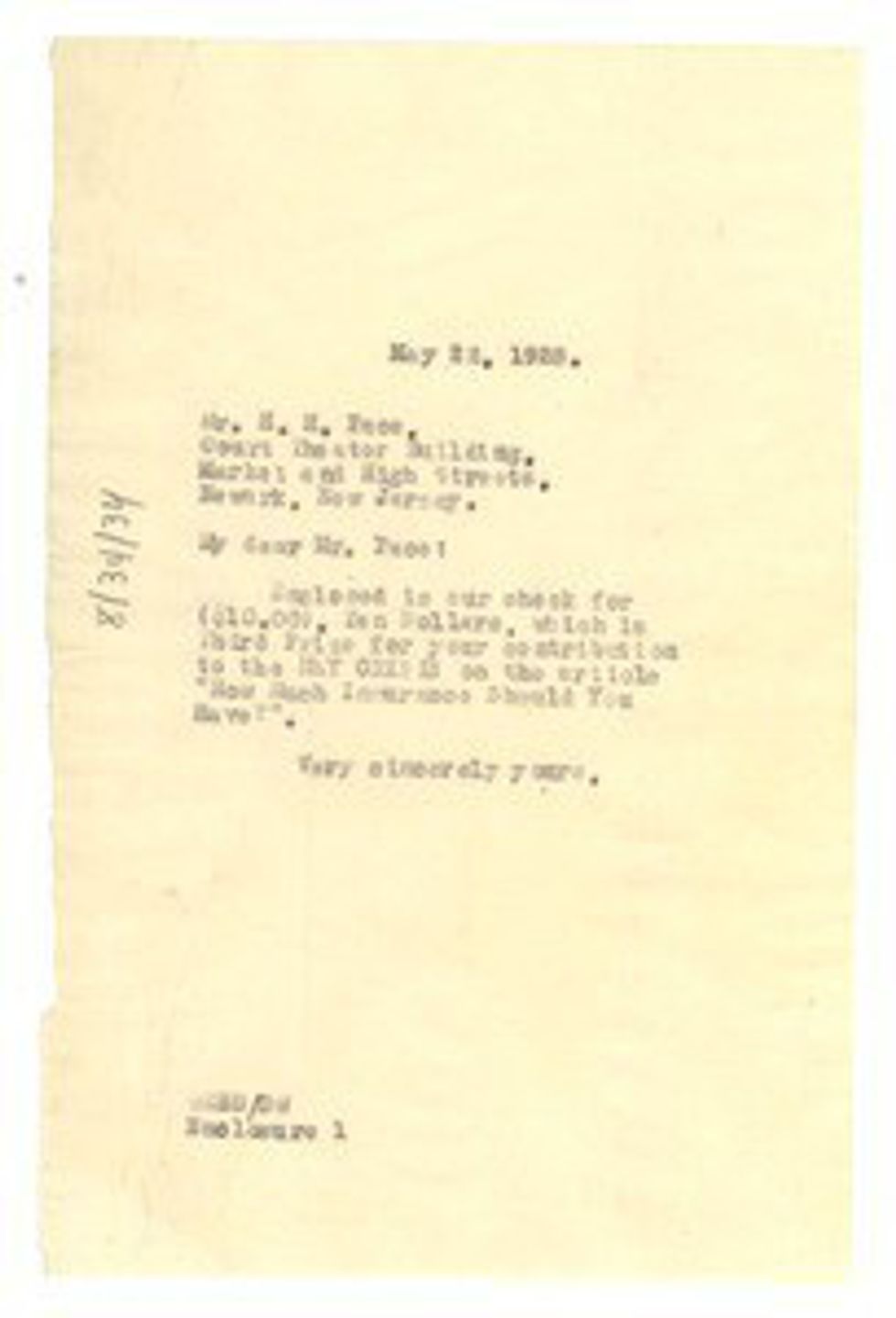

Along this entire journey, DuBois was supportive. Even in the bleakest moments, he knew that life sometimes had to deal with failure as when Black Swan was closing. In a personal letter to Harry Pace, DuBois writes: “Enclosed please find a receipt in full for your indebtedness to the Crisis. I am glad to settle it this way as I recognize the difficulties, which have faced and are still facing you. If you get your head well above water again I hope you will do what you can to float this stock for us.” This is just one of hundreds of correspondences between the two. Right up until his untimely death, Pace would always write to DuBois and vice versa. Both men supported each other’s work. It did not matter the cause nor the reason, they were there for each other. After Black Swan, Pace founded a life insurance firm. Even in this new business direction, the two could not be separated. Harry Pace, by never giving up and moving on after each trial and error had a very successful life. Although he died on the younger side, his life was full of great work and he had accomplished more than most African Americans could have during these years where racial prejudice still had a firm hold on much of the nation. Black Swan records provided a catalyst for change. It brought music and works by talented musicians into the homes of a racially diverse audience. It also glued together a symbiotic relationship between two men who were constantly finding ways to battle racial inequality. All three left a lasting imprint not just on music history, but also on the subject of race within the United States.

Du Bois, W. E. B.. The Souls of Black Folk (Dover Thrift Editions). Dover Publications, 2016 Kindle Edition.

DuBois, W.E.B. “Letter from DuBois to Harry Pace.” 30 Dec. 1924. W.E.B. DuBois Special Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst. N.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2016.

"Black Swan Records Founder Harry Pace." "Voices That Guide Us" Personal Narratives. ASCAP Biographical Dictionary, R. R. Bowker Co. Web. 08 Oct. 2016.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. "Who Really Invented the ‘Talented Tenth’?" PBS. PBS, 2013. Web. 28 Nov. 2016.

"NAACP History: W.E.B. Dubois." NAACP. NAACP, 2009. Web. 28 Nov. 2016.

Pace, Harry. "Letter from Black Swan Phonograph Company to W.E.B. DuBois." 1 Dec. 1924. W.E.B. DuBois Special Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst. N.d. Web. 12 Oct. 2016.

Suisman, David. "Co-workers in the Kingdom of Culture: Black Swan Records and the Political Economy of African American Music." Journal of American History Mar. 2004: Archive.oah.org. Web. 9 Oct. 2016.

Suisman, David. "Black Swan Rising." National Endowment for the Humanities. Mindspring Press, Dec. 2010. Web. 09 Oct. 2016.

Suisman, David. "The Black Swan." Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2009. 204-39. Print.

Wintz, Cary D., and Paul Finkelman. "Blues." Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Routledge, 2004. 141-151. Print.