Growing up as a young boy in a Catholic household, there was no room for thought in my life. Catholics have a weird way of preaching about every individual’s spiritual journey, while simultaneously demonizing going at your own pace.

There are these life stage rituals—baptism, first confession, first communion, confirmation, blah, blah, blah (I couldn’t really tell you what comes after that because I jumped ship shortly after my own confirmation). True Catholic Dogma puts no actual age on each of these, formally teaching that you should only progress if you feel called to do so by God.

But when you’re pushing these rituals on children in the second grade (which is about eight years old), you can’t honestly expect them to have a critical understanding of their spirituality. So when I say that there was no room for thought, I mean that there was no room for my own thought. I was being forced fed ideas and beliefs that weren’t my own and I was being sheltered from the parts of culture that could possibly spark independent ideas and “secular thought.”

For some, a life like mine unleashes in a cathartic college experience where there are no limits: maybe drinking to unconsciousness during welcome week, possibly snorting cocaine a month into the school year. And while I have had my fair share of questionable choices, I wouldn’t label any of them as a part of my own childhood release. I let go of my childhood over the course of three years, when I was leaving high school and entering college—I did this by getting a haircut, finding my bible, and piercing my nose.

I was 16-years-old before I was allowed to choose how I got my haircut—not that it mattered before then, I mean I could barely keep my room clean as a kid so it really isn’t like I put a lot of effort into my everyday aesthetic. And, for the most part, the Catholic School Uniforms TM and my parents held the key that locked the door to my creativity. But just before my junior year of high school, my mom told me I needed to “clean up” my hair for pictures.

I hated the way that she told me to do things. She wasn’t very commanding or authoritative but had developed this give and take relationship with me and my siblings. One of her five children wouldn’t fold their laundry ever-so neatly how she liked it to be, so she would GIVE us this guilt-stricken performance—acting like the world had ended because we needed reasons to do our chores—and then she would TAKE away all of our technology until the chores were done. Like I said, I was not a fan.

But that’s something I definitely got from my mom’s genetics: her theatrics. So being told that I all of the sudden had creative license over my own body for the first time ever was like the spark that gave fire to humankind. And thus, like an ember builds to a roaring fire, my life of subversion began and I woke from a deep, catatonic slumber.

I adopted the shaved-sides pompadour style—not that it entirely matters what it looked like because in two months I had to get it cut again, but what does matter is that my mother hated it. Every comment she made that sounded remotely like, “You were so much more handsome before!” made me smile wider and wider. The more she attempted to validate my cradle-Catholic cookie-cutter childhood existence, the more confident I grew in the path that I was carving for myself.

I came out of the closet as gay when I was 13, and I didn’t have the words to describe it yet, but I knew that to call myself a man was to short sell my true identity. So, being a young, gay, gender-fucked kid going to a private Catholic high school meant my existence was subversive and I knew that. I didn’t have a lot of role models, primarily because I hadn’t spent much time identifying traits in people that I wanted to emulate myself. My teachers were often hyper-religious Catholic-zealots and I wanted to puke at the thought of one day becoming someone just like them. That ember which sparked only a year prior, was made into a warm fire during my senior year by my AP language and composition teacher, who held similar beliefs but had developed a more “appropriate” way to disrupt the system.

Private school has a lot of things attributed to it: stricter rules, uniforms, and often a supposedly better education; private schools generally have good reputations as a result of those attributes. But Saint Phil was no Palace of Versailles. STP, as we called it, was decrepit, underfunded, and falling apart. At one point during my career in those hallways, our principal (who was also the athletic director) made the executive decision to duct tape an umbrella to the ceiling, concave up so that it could catch the water that was leaking through a crack in a frequently used classroom’s ceiling. Being able to contribute to breaking up this elitist system of for-profit educational systems founded on religious ideas of morality and understanding, was an immediate manifestation of my dreams.

Sara Muniz-Carol was the shortest, most petite adult woman I had ever met. Immediately upon meeting her, I didn’t know if I was in love with her or if I wanted to be her. She had a trendy, shorter-than-short pixie cut. Two visible tattoos, one star on her ankle and a strange looking object on her arm. When I asked her what the abstract shape tattoo was of, she said, “An elephant!”

Ms. Muniz, who allowed us to call her Ms. Carol because it was whiter—I mean it was easier to say—taught me very quickly that you could be a double agent. She and I spent hours of the first months of the year figuring out how we were going to bring social change into these halls frozen in 1950s thinking. Her mentorship culminated in one “for fun reading” assignment. I wasn’t much of a reader, and I really hated every time she tried to get our measly class of seven to be excited about reading fiction. But, without fail, every time she suggested a book for me to read, it was life-changing.

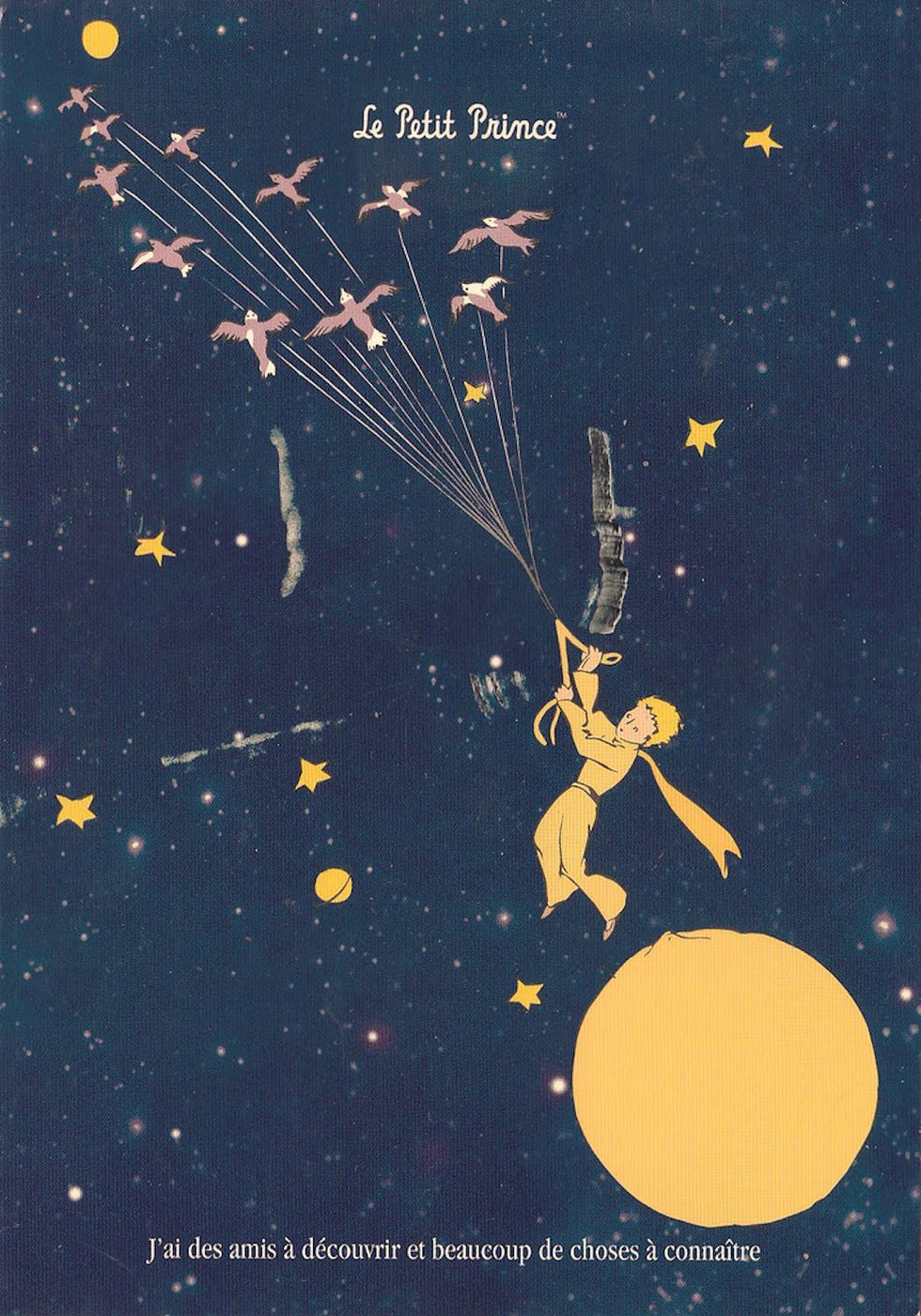

"Le Petit Prince" was no exception to that rule. When she finally suggested I read it over spring break, she gave me the last tool I needed to be successful after I left the four walls of her classroom. Ms. Muniz taught me a lot about myself, others, and how just the idea of maintaining childlike curiosity is disruptive against the Machine TM.

In only a few words the book is about one thing, maintaining childlike curiosity in the face of a creativity killing society. The school was my creativity killing society, and Ms. Muniz was my kooky old neighbor who introduced me to the stories that fill my personal bible. I was being taught every step I needed to take in order to win, as fast as possible because I only had two months left. When I felt I had accomplished enough, I let go and moved onto college where my disruption became my brand. My hair had already been as personal as this discord could get, and it was hard to tell people that a book of fiction could be an aspect of my personality, so what better way than body modification to invigorate in others what I already knew to be my truth?

That’s right, a nose ring. Without telling my parents, and with absolutely no planning, a month into my adulthood I took my body into my own hands for the second time and got my first piercing. My family hated it, they still hate it, and they will probably always hate it. And like deja vú, every teasing comment, every “joke” that was made at my expense because of this piercing, only made me smile more.

Who am I? Today, I’m more than an in-trend haircut, or a beat up, coffee-stained copy of the English translation, "The Little Prince," or an iridescent full-hoop nose ring. I am my friends, my lovers, my communities, and I am the change that we enact daily. But we would be nowhere without our histories. It is true that a hair change, a good book, and stylish piece of jewelry have the ability to break down walls of ignorance and create a revolutionary.