To the reader who might hear this and read the translation of a Biblical passage below, you might remark "Oh, it's just poor English," but how do you know it's even English? Because it has the same words? As it turns out, from 1066-1476 AD, the English borrowed a lot of French words from their Norman conquerors. Now, French-origin words consist of 25% of the entire English lexicon, so is English just a gutter form of French? A simplistic view of the language may be the reason behind such opinions without understanding the Gullah language's history and parent-languages. Yes, parent-languages, for this goes beyond the English language and into the arduous fieldwork done by the linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner, who spent years on the islands that the Gullah inhabited. He listened and recorded their speech and then compared their pronunciations to the recorded words of the people of West Africa. Turner's findings were published in his book "Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (1949)".

To provide historical context, the Gullah language is spoken by the descendants of African slaves along the South Carolina and Georgia coastlines, in the islands Hilton Head, Sapelo, Wadmalaw, Daufuskie, etc. These slaves came from coastal West Africa, specifically from Nigeria to Angola. The English language was implemented upon them in order for them to communicate with overseers and the land-owners. While slaves who spoke the same native languages were moved around away from each other to prevent plots of rebellion, the emerging language simply expanded. This is usually how creole languages are formed, by raising generations of people speaking the means of communication between the ruling class and the slaves as a native language.

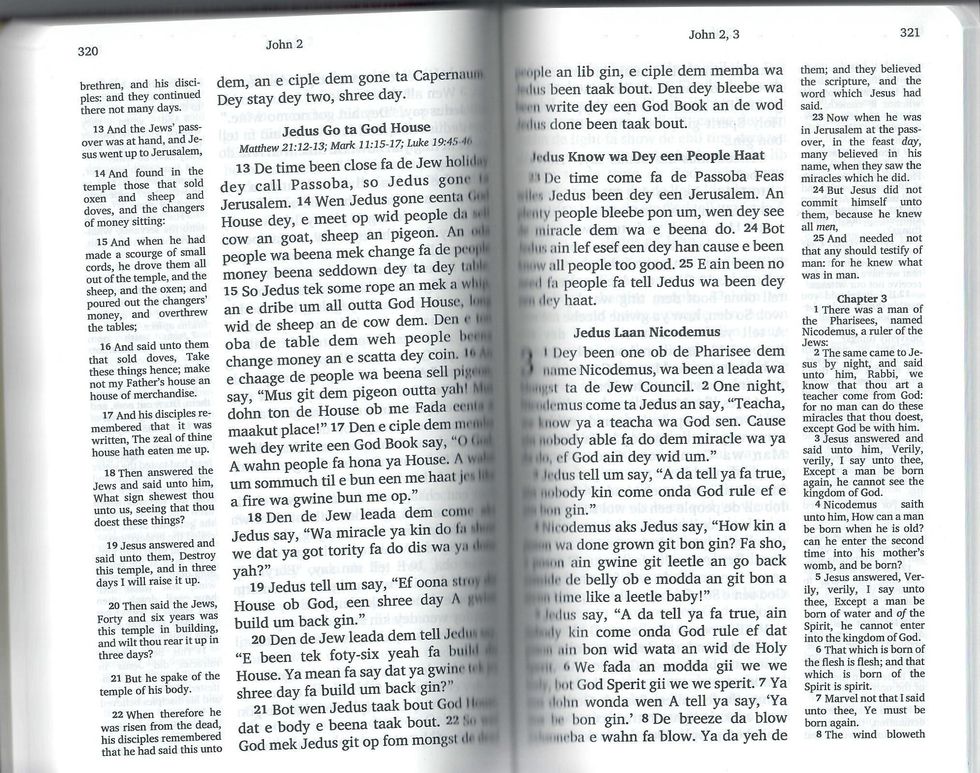

One crucial part of the language that the slaves inherited from their African languages was their pronunciations. A common feature in words that, in English, start with the pronunciation [yoo] end up being sounded as [nyoo] in Gullah; such as united: nyunited; use: nyuse; and young: nyung. This sound is called the palatal nasal and is found in Ewe, Efik, Ga, and Nupe. The way it was written varies, since Lorenzo Dow Turner used the International Phonetic Alphabet to accurately record it, while the Wycliffe Bible Translation (from the picture above) and Virginia Mixson Geraty, author of "Gulluh fuh Oonuh (Gullah for You): A Guide to the Gullah Language," used slight modifications of the original English words. It would not be a simple coincidence if their original languages managed to seep through.

If anything, the language serves as a testament to the endurance of the Gullah people in American history. The Gullah word for "money," which is babbidge, comes from the word "babbit," which were metal coins used as currency in plantation commissaries. Just a single word can provide a glimpse into the value behind it and what it represented, as in the case of the Civil War being referred to as gun-shoot; with fo-gun-shoot meaning "before the Civil War" and attuh-gun-shoot meaning "after the Civil War." There is also vocabulary within the Gullah language that can be traced to the languages that the original slaves spoke. There are words such as de which from Ibo means "to be;" kootuh: "turtle" in Malinke; oonuh: "you" in Ibo; buckruh: "a white person," from Efik meaning "he who surrounds;" and tabby house: "cemented house," which came from the mixture of cement, oyster shells, and pieces of brick used by African Muslims when building a house.

There are also Gullah words and phrases that are direct translations of the African phrases, such as describing someone who is covetous as big eye, just as in Ibo. The Gullah word for "dawn" is day-clean, which comes from the same Wolof etymology for "dawn." To call someone an honest person in Gullah is to call him/her a trut-mout, which comes from the Twi expression anokware meaning "the mouth true." While these Gullah sample sentences: "he gone," "he been gone," and "he done gone" appear to look like incorrect English, they are reflections of grammar from African languages, specifically with the use of past tense. In those languages, spoken by the first slaves, it uses the near past (in the case of "he gone"); remote past (by using "been" in "he been gone"); and a completed action ("he done gone").

Reduplication, when intensifying a word, is also a feature of Gullah grammar as well as several African languages. The reduplication for dey, which is Gullah for "there (indicating a general location)," is deydey, which is "there (indicating a specific location) or correct;" just like in Kongo lunga means "to take care of," while lungalunga means "to take good care of." One of the few occurrences in English for reduplication is very, as in describing someone as "very, very mad."

But, even with all of these grammatical rules and African-origin lexicon, it still might be looked upon as a dialect; even the title of Dr. Turner's book calls Gullah a dialect. What makes a dialect different from a language is that although a dialect consists of its own variation of grammatical rules and lexicon, a language is a system of communication that develops independently from the other dialectic variations of the same language for political or geographical reasons. In the case of the Gullah language, it developed in isolated parts of the American colonies. As seen from the Biblical passage above, it also has a slight degree of unintelligibility, making it distinct from any American English dialect (which is also why there are English translations on the fringes of the pages).

Researcher Melville Herskovits has studied cultures of coastal West Africa and how much of them were maintained by the slaves and passed down. They were studied in places such as Guiana, Haiti, the Caribbean, and in the United States and the Gullah-speaking area (the latter two were considered distinct). He found that the language of the Gullah people was "quite African." While the interpretation is not meant to become dogmatic, it still provides credence to the Africanness of the Gullah language. Based on my analysis of the Gullah language, the African and English languages are the parent-languages that pass on phrases, grammatical rules, pronunciations, and lexicon. I will say that it is uniquely African in the face of slavery. It brought the African languages they originally spoke as a way of creating an identity out of those conditions and applying them to everyday life.