Prep-Tober, as I have come to know it, are the steps one takes in October to prepare for writing a novel in November (or any month). I first came upon this terminology in Rachel Stephen’s video, which described what she will be doing to prepare for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) in November. Since seeing that video, I have become aware that it is a common term for describing to prepare for such an obstacle as writing a novel in a month. It made me think about the many different methods on constructing and preparing a novel. The intention of this article (and the ones to follow) are to help elaborate on different techniques to prepare to write for those individuals attempting their first novel, or for those who are looking to try a new method. This week’s issue of my "Guide to Prep-Tober" will focus on plotting.

Are You a Plotter or a Pantser?

The spectrum of writers varies between “Pantsers” and “Plotters.” Essentially, pantsers want to plan very little or none at all. They get their name from the idea of “writing by the seat of their pants,” also known as plunging into a story based on one idea. On the other side of the spectrum are Plotters, who want to plan just about everything. Plotters themselves vary by the degree of plotting -- see below some different methods of plotting fiction novels.

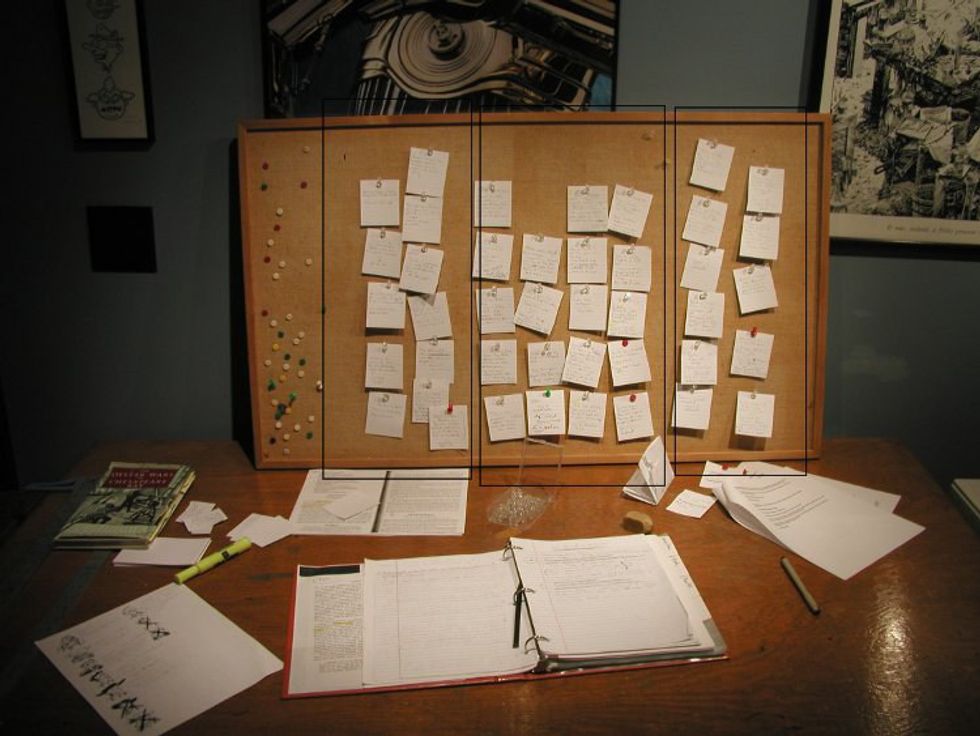

Note cards.

If you're a plotter, you like to work with physical plotlines -- ones that can be moved around, taken out, or replaced easily. It goes back to the old style of posting note cards or flashcards onto a corkboard. This is one of the most hands-on method of plotting. It gives you the freedom to change the setup of your story later on. The whole construction is placed entirely in your hands, even choosing how many flashcards to use. Some people prefer going by each chapter, or even scenes, so they aren’t limited to writing within chapter sections. I’ve seen some people put who is in the scene, what the conflict is (say, maybe someone is moving, which starts their storyline), and what they want to get across with the scene. You can use different push pins to indicate different points of the story (beginning, climax, resolution, etc.) or even different colored note cards. The discretion is up to you, which is thrilling. Here is an example of plotting using note cards for those who want a more in-depth example.

Worksheets.

Worksheets are for the people who want structure, but mainly want to focus on the overall picture. Since worksheets are made by other people, generally, there is less control on what you can cover. That being said, you get to choose what to fill the blanks with. Some follow the overall structure of the novel with what they want to happen, but without any specifics – for example, you might put how it starts and several middle points but not what’s in between, so you know what you are writing toward without being too overly structured. On the other hand, some might go into depth analysis of when to write scenes in a very specific order. It’s just a matter of finding the right worksheet for you. Here are some free worksheets to use.

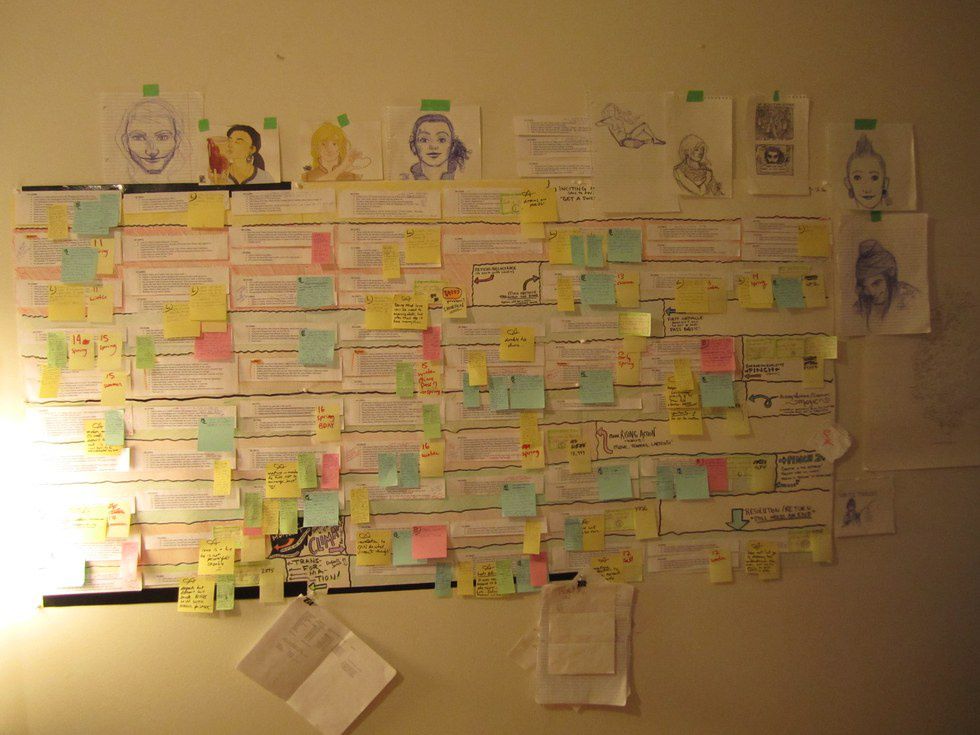

Story boards.

Story-boarding is essentially a more elaborate version of the note card method. Once again, it is up to your discretion, so you can take this however you wish. Borrowing methods from our screenwriting pals, writers have adopted this method of outlining. As seen in the above picture, you can add illustrations or pictures of your character inspirations or additional notes using sticky tabs. Some visual authors who want to be more authentic to the original storyboard method will draw out scenes (this also works well if you are working on a graphic novel). If you do want to draw out your scenes (or just some scenes), it may take a while depending on how fast and how detailed you plan to make such images. This is also the place to become more in-depth with your scenes. You could write out and/or print a scene you plan to insert into the novel during the writing process and build around it with descriptions of what will help you most while writing (whether that be setting, characters actions or appearances, motivation, etc.). You can find a more thorough explanation of story boarding for novels here.

Loose outlines.

This is probably the method I apply the most to my writing. What I consider a “loose outline” follows a classic essay-style format. By “classic,” I mean the five-paragraph essay you were most likely supposed to write for your English class. However, since this applies to novels and scenes, it can be as long or short as you want it to be. You have one heading (either a chapter title or just scene title) with a sub-point that tells who is involved and where, and then another sub-point that goes into a deeper explanation of the scene. These sub-sub-points can be as detailed or minimal as you decide depending on how much of the scene is figured out. The reason it is a loose outline is because, like the others above, it doesn’t need to completely figured out. It is basically a glorified guide on how you plan to navigate the novel while you are writing. Since the loose outline is essentially a guide, you can deviate from it and continue on a different path if your story takes you that way. That being said, I prefer this method because if (honestly, more like “when”) I deviate from the storyline and get lost, I have something to reel me back in so I know how to continue.

Stream-of-conscious.

This method is pretty much how it sounds. Some writers choose to write their novel idea out completely as they see it in their head. It doesn’t have to make sense at first because it’s literally how you see it at the time you sit down to write. After, you can choose to rearrange the plot points and inject more and show the step-by-step actions to get to the climax and end of the plot. This works on computer software, like Word, or a sky drive of some sort. It’s a bit like the other methods mentioned above but written out in the same style you plan to write your novel in, so some writers find it easier to translate the outline to the actual writing of the novel.

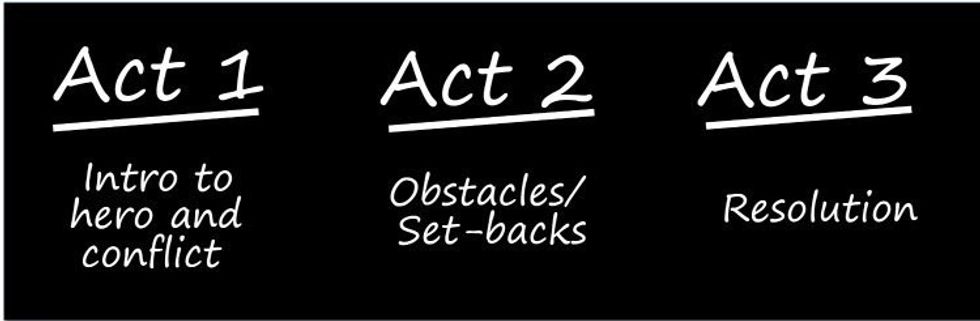

Three-act structure.

The three-act structure is one of the more structured methods of plotting. This method is for those who have the majority of their story figured out and know what goes where. It may also helpyou to fill in the blanks on certain plot points if you don’t have everything figured out. The main setup is pretty self-explanatory: the outline is broken up into three different “acts,” or sections, of the novel. These acts are generally the beginning, middle, and end. Of course, each person can apply this differently to their own projects, but if you want to follow the method, each act has about nine “blocks,” or scenes, in each of them. This allows for about 27 chapters if you use each block as a chapter, but some people will deviate and add more chapters depending on the natural progression of the novel. For the most part, this method works best for action-oriented novels if you follow the specific “title” that follows with each block. If you want a more detailed description of what goes into each block, here is book-vlogger Katytastic’s example of the three-act structure.

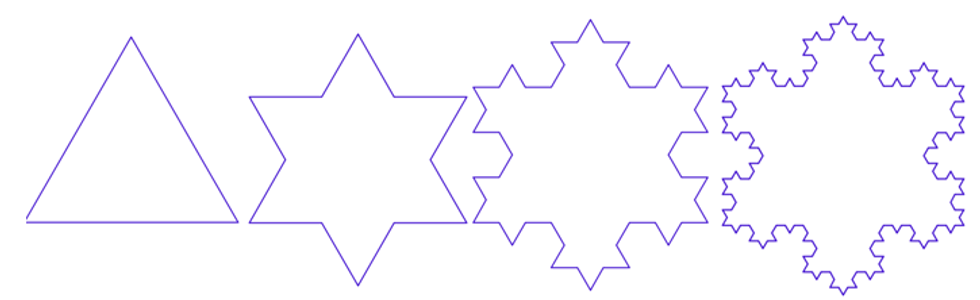

Snowflake method.

The snowflake method is also one of the more structured and detail-oriented plotting method. This is one method where you start with an idea and branch it out multiple times. It is also one of the methods that takes quite some time before it is finished or before you may be satisfied with how it looks. Above is an example of how the snowflake method works. (Some writers also recommend to start with an unedited stream-of-conscious writing outline before starting this outline.) Essentially, this method is a mix between the stream-of-conscious method and the three-act structure method. You can build one small idea up until you are ready to start writing the novel. You start with a sentence describing your novel, then work up to a paragraph describing the beginning, middle, and end. Then, you move to characters and how they fit into the plot, etc. For some people, it makes the sense of writing a novel less daunting because you are taking each step to prepare to write a novel one step at a time rather than diving in full-force. If you would like a more specific example of what the snowflake method looks like, you can find the creator, Randy Ingermanson's, description of it here.

Since no one way of writing could be considered the “right” way of writing, any of these methods could work for you. Some of these plotting methods also cross over each other to create something new, so any method could be created on your own, as long as it fits your style of organization and how much you want to know before writing your novel. These are also just a few of many plotting methods, so I encourage you to explore the internet to see what you feel is the right method for you if it wasn’t among this list.

What's your favorite plotting method? Or do you prefer to pants it and dive head first?