Prep-Tober, as I have come to know it, are the steps one takes in October to prepare for writing a novel in November (or any month). I first came upon this terminology in Rachel Stephen’s video, which described what she will be doing to prepare for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), which takes place in November. Since seeing that video, I have become aware that it is a common term for describing to prepare for such an obstacle as writing a novel in a month. It made me think about the many different methods on constructing and preparing a novel.

The intention of this article (and the other ones in the series) are to help elaborate on different techniques to prepare to write for those individuals attempting their first novel, or for those who are looking to try a new method. You can also check out the previous weeks' articles on plotting methods, world-building, and characters. This week’s issue of my "Guide to Prep-Tober," and the final issue in the series, will focus on genre.

Why knowing your genre is important.

Knowing the genre you are writing in is important because it allows you to know the writing styles and techniques common in those groups of novels. Of course, some people prefer to look at genre after they’ve written their novel, focusing on the aspect of storytelling before all else, and that is a perfectly valid technique. Knowing genre before, though, affords you the ability to know how to structure certain aspects of the novel. Most writers write because they dream of seeing their novels published, and knowing the genre will also help literary agents and publishers know how to best market your novel. Understanding your genre, or even sub-genre, will help you pursue the novel writing process easier.

Is this a genre?

The constant debate questions whether "young adult" literature is a genre of its own. I believe it is its own field, not a genre, just as children’s and adult literature are their own fields. Genre doesn’t categorize by age necessarily, though it is important to define who the audience you are writing to is, but it groups together common themes and scenarios into the plot.

Below is a list of popular fictional genres and what some of them consist of:

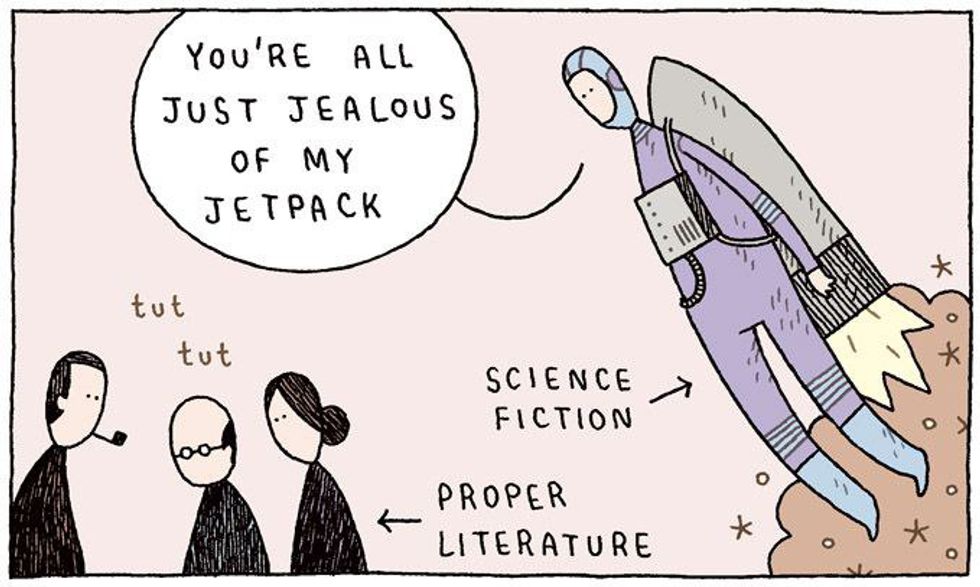

- Science-fiction: "Ender's Game" by Orson Scott Card, "Cinder" by Marissa Meyer, "The Martian" by Andy Weir, and "Divergent" by Veronica Roth.

- Adventure: "The Hunger Games" by Suzane Collins, "The Maze Runner" by James Dashner, "City of Bones" by Cassandra Clare, "The Lightning Thief" by Rick Riordan, and "The Hobbit" by J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Mystery: "Gone Girl" by Gillian Flynn, "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo" by Stieg Larsson, "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes" by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, "Along Came a Spider" by James Patterson, and "The Da Vinci Code" by Dan Brown.

- Romance: "Pride and Prejudice" by Jane Austen, "Outlander" by Diana Gabaldon, "A Walk to Remember" by Nicholas Sparks, "Whiskey Beach" by Nora Roberts, and "Anna Karenina" by Leo Tolstoy.

- Horror: "Dracula" by Bram Stroker, "The Shining" by Stephen King, "Coraline" by Neil Gaiman, "House of Leaves" by Mark Z. Danielewski, "The Huanted Mask" by R. L. Stein, and "The Silence of the Lambs" by Thomas Harris.

- Fantasy: "A Game of Thrones" by George R. R. Martin, "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" by J.K. Rowling, "The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" by C. S. Lewis, "Eragon" by Christopher Paolini, "Vampire Academy" by Richelle Mead, and "Inkheart" by Cornelia Funke.

- Realistic: "The Fault in Our Stars" by John Green, "Thirteen Reasons Why" by Jay Asher, "Speak" by Laurie Halse Anderson, "Eleanor and Park" by Rainbow Rowell, "The Perks of Being a Wallflower" by Stephen Chbosky, and "Holes" by Louis Sachar.

- Historical Fiction: "The Book Thief" by Marcus Zusak, "The Pillars of the Earth" by Ken Follet, "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee, "Atonement" by Ian McEwan, "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas" by John Boyne, and "The Help" by Katheryn Stockett.

Of course, this is not a complete list of all genres out there, and if you are having a hard time pin-pointing what you think your novel is, you can check out these links: "Genres of Literature," Writer's Digest's "Definitions of Fiction Categories and Genres," Writer's Digest's "Sub-Genre Descriptions," and Mark Nichol's "35 Genres and Other Varieties of Fiction."

Motifs and archetypes.

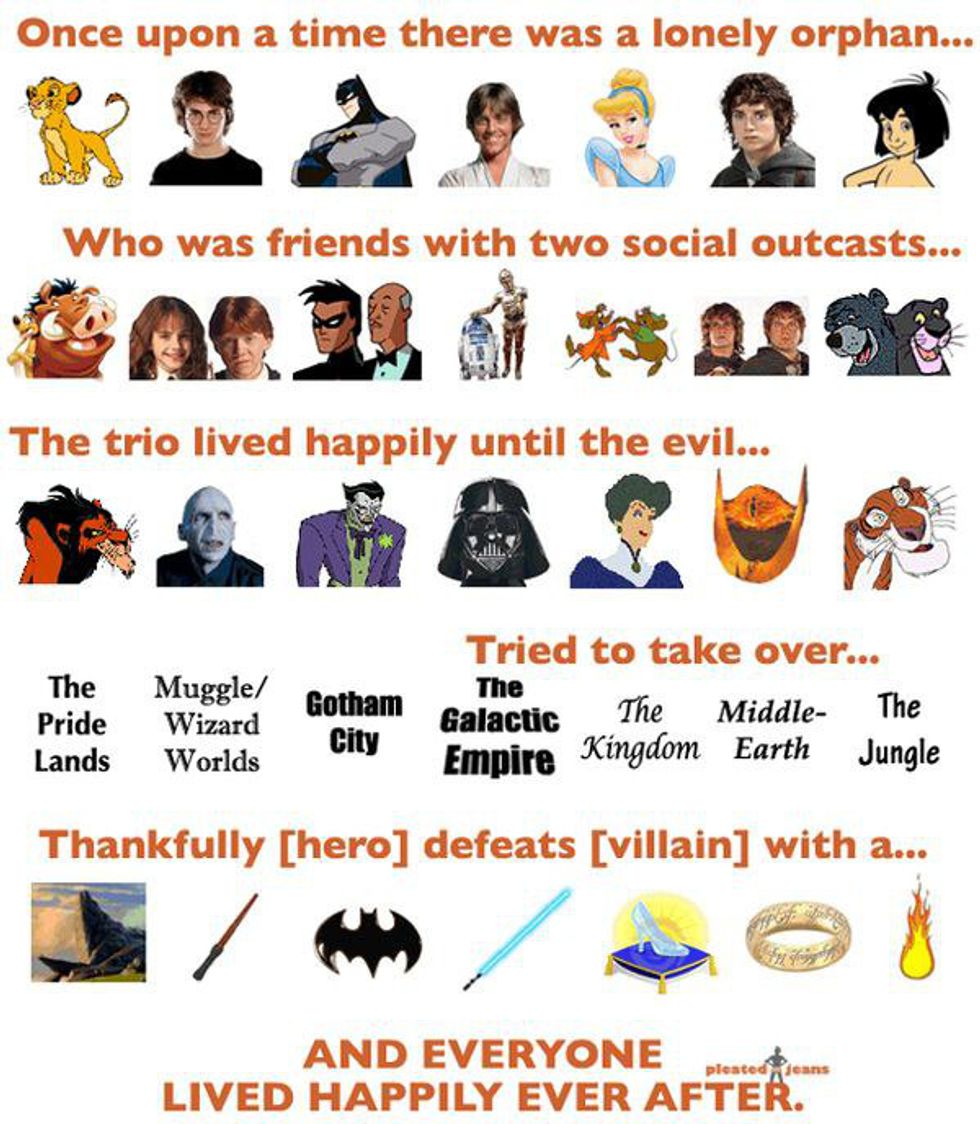

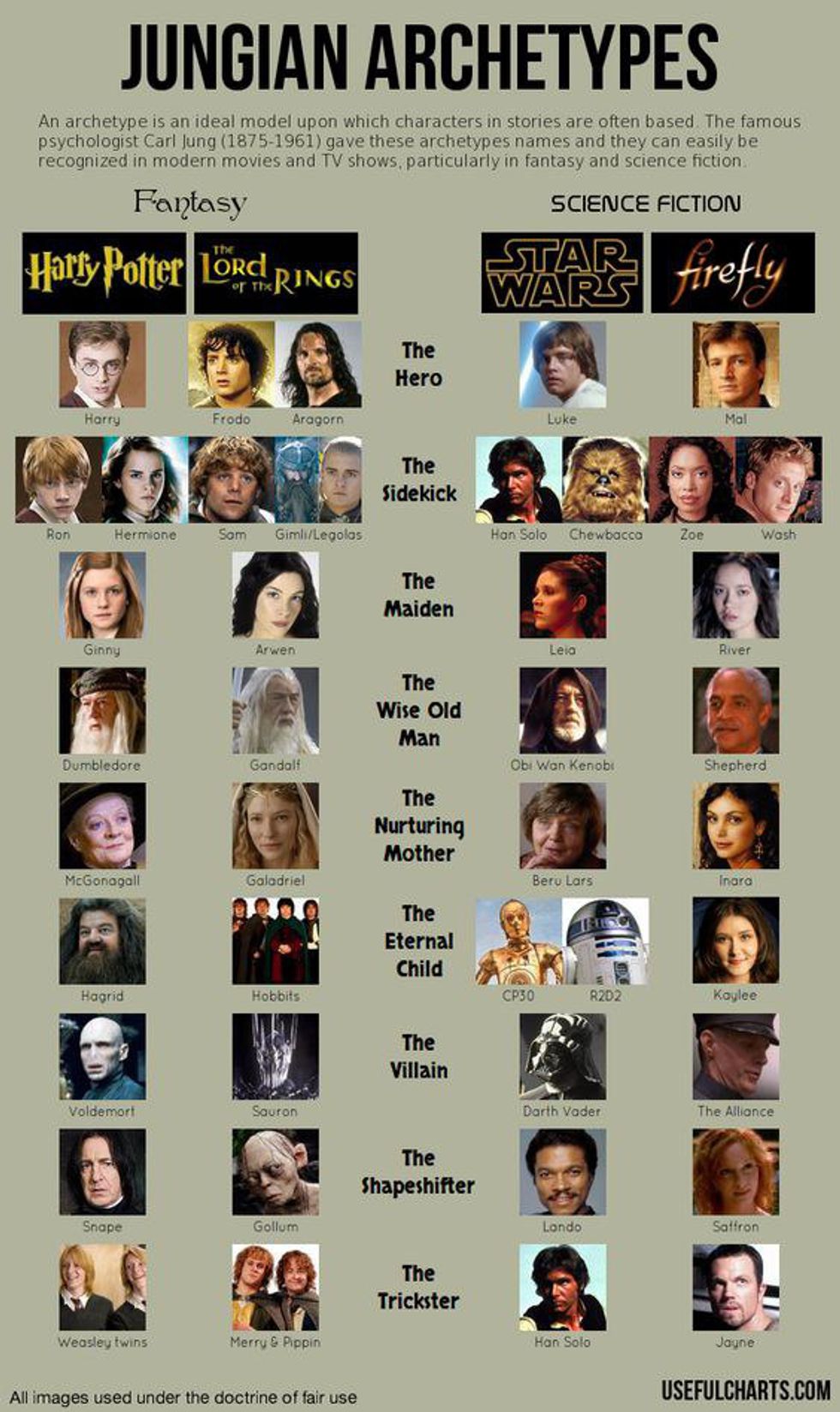

A motif is any recurring element of a story that poses symbolic significance. On a much broader end, an archetype is a character or motif recurring in multiple works of fiction. So when finding your genre, you should look into the common archetypes that one might find in those works and see what does and doesn't work for the story you want to tell. Knowing different archetypes can help you start constructing a plot for a novel if you are struggling to expand your basic idea. Then once the first draft is finished, you can revise and edit to see if you still want to follow these archetypes, or if you want to find a pattern that better suits the story you are telling.

For example, when telling the hero's journey in (usually adventure) novels, you might come across this pattern:

Or, if you want character archetypes that fit across genres, you can look at character archetypes that many novels and movies have adopted. This can help you start constructing a novel plot -- if you feel something is missing, maybe you need a certain character for your main character to seem whole. This list is based only on fantasy and science-fiction characters in this situation. However, they can be applied to many genres of literature.

If you still want more information on archetypes, you can follow these links: Carl Golden's "The 12 Common Archetypes," Glen C. Strathy's "Creating Archetypal Characters To Fill The Dramatic Functions In Your Novel," and Graeme Shimmin's "Story Archetypes That Make Your Novel Resonate."

Finding a genre that fits your novel can happen both before and after the writing process, and can change drastically if you decide on one genre before writing, depending on the editing process. Genres are useful in knowing which direction you want your novel to go in and work just as well as a border. If you cross the border, you have to start looking at sub-genres, or even niche genres, depending on the topic. Genres give you a marketability and help you easily identify the competition of stories being sold. While genre is important to know, focusing on the story you are telling is the main goal when writing; genre just gives you an easier sense of boundaries in what you cover in the novel.

What is your favorite genre to read?

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by