My mother, Sally Clyburn, grew up in Lancaster, South Carolina, where the McDonald's sweet tea was syrupy, the population under 10,000 and the median income a couple thousand above that.

My father, Howard Rothkopf, was born in Brooklyn but grew up in Jericho, New York in a heavily Jewish and Italian neighborhood, where the median income was, let’s say well above Lancaster’s.

Needless to say, they were and are very different people with very different backgrounds, families and even religion. But they made it work and I never felt anything other than assured in their parenting styles, different as they were.

But the other day, I asked my mom what their plans had been in regards to any sort of religious upbringing before having us. She told me they were going to “wing it” (they really aren’t big planners). So they decided to culturally give us both rather than ingrain the religious aspects of each.

From my end of things, that’s been pretty true. I was born and lived in a primarily Jewish town through the age of about six before I moved to Charleston, a majority Christian-populated city.

Each year, we lit the candles on the Menorah, said the prayer and instead of a gift for each day of Hanukkah, we each got one larger present. Then we put up our tree and woke up on Christmas morning and celebrated that as well.

It’s interesting. Having grown up a bit I’ve realized that as a child, there are questions that you do and don’t ask yourself.

You might wonder why it is that the sky is blue and you might think up a thousand and one “what if” questions to berate your parents with, but when did religion ever come up as a question? Questions themselves are posited when a person is encountered with a lack of knowledge or a challenge to believe.

Growing up, I called myself, “half-Jewish, half-Christian.” As if religion were genetic in nature.

I didn’t question meaning behind each of these words. I was whatever my parents were, like many of my classmates. But rather early on, my classmates and friends challenged this belief when they told me that you can’t be half and half.

“That doesn’t make sense,” they said.

“I’m Christian and I don’t believe the same things as Jewish people, so you can’t be both,” they said.

I didn’t really understand. I was selfishly proud to be different, to be something other than what everyone else was in my grade, which was especially uniform at my school. But now that wasn’t possible, it wasn’t within the parameters of a strict set of rules that set the guidelines for differentiation between two religions.

My freshman year of high school came and I was placed into a sophomore English class. I was a little less confident back then and I can remember telling myself to not say something stupid, to just be quiet, to make sure that none of the cool sophomores thought I was weird.

One day, my teacher decided to do an exercise in acceptance of difference in opinion. She would make a statement and you would go stand by strongly agree, agree, don’t have an opinion, disagree, strongly disagree.

She started out with easier statements that progressively got more controversial. And then I heard, “My religion is the one true religion in the world.”

I remember thinking, ‘Oh this is an easy one!’ and immediately moving to the strongly disagree side.

I looked up to find myself completely alone. Then, I started denying and arguing with every single person I saw under the taped sign, ‘strongly agree.’ This was one thing I knew not to be true. My parents were both right, these people are saying that one of my parents has to be a liar, how could they be so wrong?

I honestly couldn’t believe it. I sat for the remainder of the activity.

By the time my junior year came around, I was a blade of grass in a field of “What even is a religion?”

On standardized tests, I would look at the religion section and pick and choose what I was going to be that day. Sometimes it would be “would prefer not to say.”

At 19, I still don’t have a set opinion. But I’m going to be honest with you, at 19, I also really don’t care. Since that time, I've grown into myself, become more aware of my own strengths and weaknesses — I've developed my own sense of right and wrong.

Sure, I could write about a hole that lack of religion has left in my life or I could write about the importance of spiritual support, if I thought I was in the midst of some kind of identity crisis.

But really, until I encounter a loss of faith in myself and humanity, I’m sincerely okay just living my life as a girl with a good family support system and an idea of where she wants to go and what she wants to do.

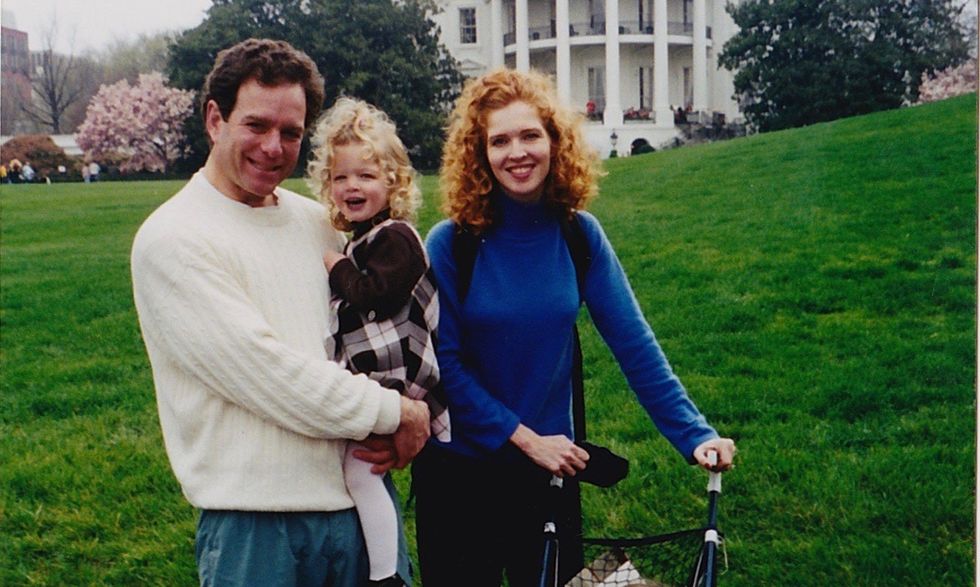

And, I think that’s what my parents wanted to leave us with when they decided not to push two religions at us. That is me and my siblings.

Religion doesn’t mean judgment, which is what I, my classmates and even my teacher had difficulty understanding my freshman year of high school. It doesn’t mean condemning other faiths or systems of belief — my parents are the counter-argument to that.

My siblings and I aren’t some convoluted mixtures of two opposing ideas. We are the example of acceptance and coexistence.

And, that’s a pretty beautiful thing.