“The lack of fish was the most shocking thing. In broad terms, I was seeing a lot less than 50 percent of what was there [before the bleaching]. Some species I wasn’t seeing at all.”

Justin Marshall, an investigator with the citizen science group Coral Watch, had just completed a survey of the Great Barrier Reef near Lizard Island. His discoveries, as relayed to The Guardian, were grim.

A natural wonder, Australia's iconic Great Barrier Reef is the largest collection of coral reefs in the world, visible even from space. A sweeping mosaic of life calls the Reef home, from sea cows to dolphins: UNESCO reports "1,500 species of fish, about 400 species of coral, 4,000 species of mollusk, and some 240 species of birds." No other World Heritage site contains this level of biodiversity.

Beautiful as it is, the Great Barrier Reef's in danger. Rising ocean temperatures are leading to a single phenomenon, one that's affected over ninety percent of the Reef: bleaching.

1. What the heck is Bleaching?

Coral is naturally bone-white. The bright range of color below is actually a tiny marine algae living on the coral. Coral gives its algae a "home base," so to speak, and in return the algae provides food for its host.

Hot temperatures sour this relationship. Coral is happiest within a very narrow range of water temperature; when things heat up, the stressed coral kicks its algae out.

The result? Seascapes like this.

An important distinction: bleached coral doesn't mean dead coral. Ocean temperature isn't constant; bleaching happens to various degrees, and always has. Nature's tough. If temperatures cool down once again, algae can return and the reef may recover.

If not, though, the coral--deprived of algae, its energy source--starves.

And when coral starves, the reef transforms. Smaller fish depend on coral for food and shelter; there's little reason to stay once it dies. The bigger fish which eat the smaller ones disappear in suit. Marine birds follow their food--the fish.

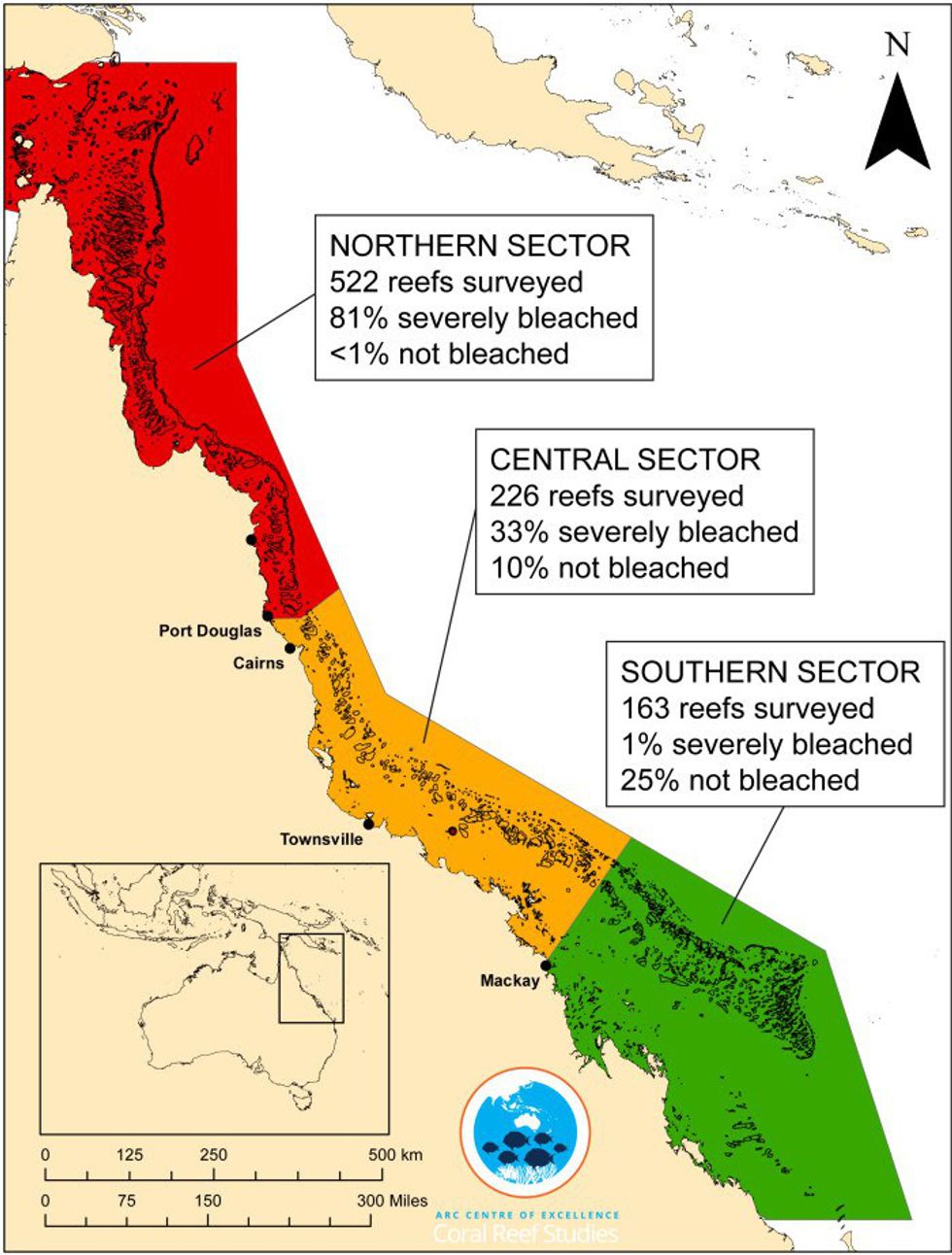

Australian scientists reported in April that "...only 7% of the coral reefs across the Great Barrier Reef have completely avoided bleaching." The northern sector of the reef was hardest-hit, with 81% ruled Severely Bleached.

2. What can we do to help?Rising ocean temperatures are the result of rising global temperatures. Right now, the only way to reverse this uptick in heat is to "dramatically reign in our emission of greenhouse gases."

Great, but how? Our society runs on fossil fuel, and it can seem impossible to tackle an issue as large as that. The secret's in chipping away at that issue, a little bit at a time: we can all take steps to reduce our impact. Reduce your carbon footprint. Try to bike or walk when possible. When driving, don't do it "pedal to the metal."

Scientists across fields are surveying the damage and making every effort to reverse bleaching. The Southern sector of the reef is in relatively good shape for recovery--but only if its environment allows it to heal. Rising temperatures weaken its shot at survival. So does pesticide and chemical runoff from agriculture. So do oil spills: Queensland authorities recently tracked down a ship which spilled 15 tons of oil off the Great Barrier Reef.

If we truly want to preserve our natural wonders, we can't sit by, wishing they'd stay the same. We have to take action and protect them. Nature is resilient, and the Reef may still survive--but only if we ensure the ocean is a place where survival is possible.