There have been many great novels written by Americans: the Grapes of Wrath, The Great Gatsby, Tom Sawyer, To Kill a Mockingbird, the list goes on. But for the U.S. and the world if you place ‘the’ before the words ‘great American novel’ one book rises above the rest. A monumental work of research and a character study, in addition to be a fantastic romance. The work is of course Margaret Mitchell’s ‘Gone with the Wind’.

The novel runs over 1000 pages and covers only around twelve years in the life of one woman, living in one state, in one small area, in what is now the Atlanta metro area. The change that takes place is rapid and swift, like Scarlett’s temper. The book opens with a giddy sixteen-year-old being courted and the easy grace of days gone by. It closes with the disillusionment of adulthood finally crashing down on Mrs. Butler’s head. Two years shy of thirty and she has married three times, lost both her parents, had three children, and seen the downfall of her whole way of life. She’s fought Yankee soldiers, carpetbaggers, and the judgemental frowns of her whole acquaintance, save Rhett, Melanie, and Ashley.

The novel is as conflicting as the feelings one has about the heroine. One reads Gone with the Wind and is uneasy with the themes of slavery and how women are treated. One gets to know Scarlett in the book and is uncomfortable with how much admiration she earns even while she proves herself an unscrupulous fool who chases chimerical childhood fantasies and cannot appreciate things until she has lost them.

Gone with the Wind is a monument to the American South, but more than that it is a bastion in the world of literature. Written by a woman, about a woman, it supersedes the genre of Romance and is simply a novel. Like all truly great novels it has a vast cast of minor characters who come and go and take bits of your heart with them. It is a study of human nature, with its terrible frailties and magnificent triumphs. The book gracefully weaves around the theme of honour and the forms it takes. Ashley has his antiquated but admirable honour of the gentleman-planter. Rhett has the honour of a man who tends to find himself doing the right thing, as much as he’d rather not. Melanie has the quiet graceful dignity of the antebellum matron who is strong as steel while being gentle as a dove; the true Steel Magnolia. And Scarlett, like Rhett, is a creature of honour in spite of herself. Whereas Rhett tries to thwart the expectation of honour, but falls into it anyways, Scarlett tries to live the life of a Southern Belle while inwardly revolting at it and seeking ways to appear a lady while she goes for the practical solution. But her honour will not allow her to see her family starve, won’t let her send Ashley and his family away after their tempestuous moment in the orchard, won’t let her speak her mind, on all but a few occasions, when she would very much like to. She takes care of the people around her, even those she can’t stand, like her snivelling sister Suellen, and her rival in love, Melanie Wilkes.

Written when survivors of the War Between the States still lingered on this Earth, Margaret Mitchell had eyewitnesses to the scenes she described. She wove a realism throughout this epic. Her narrative has the visceral quality of the horrors of war and living through it. She blends the gaiety of a ball and the dread of a town burning with equal skill in the same work. She covers the sickening scenes of injured men with a poignancy that brings one to tears, while being just as adept at bringing to life romantic banter over a new bonnet. The trembling of a kiss and the thundering of a canon are both brought thrust upon the reader in such a way that you feel you are living alongside Scarlett O’hara through the twists and turns of her life. From the famished desolation of the return to Tara, to the sickening shame of the party as she goes dressed in red to match her face of shame.

Gone with the Wind has the quality of being re-readable, for anyone who has the fortitude to tackle the massive volume a second (or more) time. You come back to it and smile at the familiar passages that stayed with you from your first reading. You find yourself confronted with reassessing the judgements you had made on characters previously. Perhaps Charles Hamilton was not as weak and foppish as he seemed the first time around. Maybe it’s as much Rhett’s fault as Scarlett’s that their lives fell apart. You leave another reading of it with an even fuller view of the world of the South and of the fictitious but completely believable characters that inhabited it.

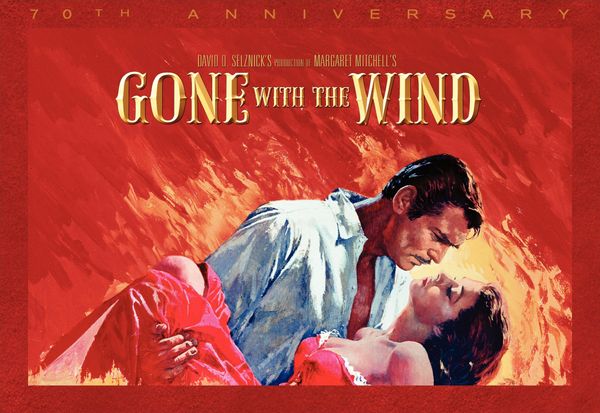

This is why: above the satire of Twain, the realism of Steinbeck, the disillusionment of Fitzgerald, and the intimate hominess of Harper, Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind rises to the top, the pinnacle of literary product in America. A complete novel, much the same as Hugo’s Les Miserables, popular with soldiers at the time Gone with the Wind is set, though less cumbersome with philosophy and minutiae. The fullness of the book, like the fullness of the life Scarlett leads, is why it is such a classic. It’s the reason, why after more than 75 years, both the book, and the movie that rapidly followed, are still beloved by so many. Gone with the Wind is a slice of history gently eased on you in the form of a story that shines with life-like characters who grip your heart, and a narrative that pulls you in tighter than a hug from Mammy’s arms. .