In light of the many structural problems that Southeast Asia faces: corruption, the suppression of civil liberties, and authoritarian regimes. Another much deadlier crisis is bubbling in the area.

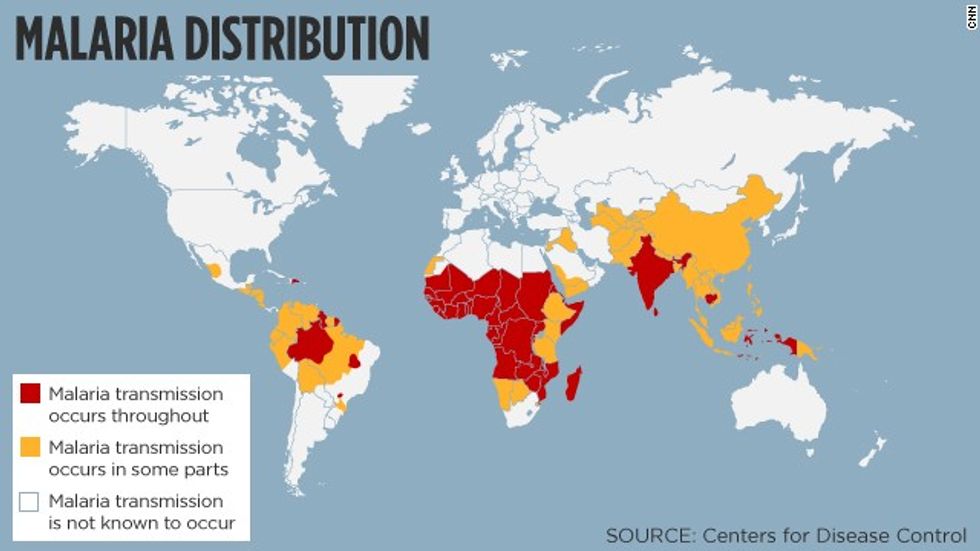

Malaria, a mosquito-borne disease most prevalent in the tropical and sub-tropical regions around the equator. The most effective treatment is a two-drug combination containing artemisinin and piperaquine. For a long time, we were able to keep malaria under control. Rates of infection have decreased, between 2010 and 2015, the rate of malaria incidence fell by 21% globally. According to WHO estimates, there were 212 million cases of malaria in 2015, with only 429,000 deaths. Antimalaria drugs have been a huge success, not only for travellers from the West but for the locals of these high-risk populations. Malaria is now seen as a form of market failure, often associated with poverty in Developing Nations, and the downsides to economic development.

However, we now face a growing crisis that will prove to be a wakeup call; drug-resistance. A new strain of malaria, now developing a resistance against the traditional two-drug treatment is hindering the worldwide eradication of the disease. This increases the possibilities that cases of incidence and higher death rates may occur, and disproportionately affect vulnerable populations in Africa, and other developing countries who already lack the facilities and budget to face these prospects. This would be especially fatal in Sub-Saharan Africa, where about 3,000 children pass daily due to malaria infection despite the widespread use of the two-drug treatment.

This strain of the disease was initially tracked in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos. However, when it was discovered in Bihn Phuoc, Vietnam, it was reported in the issue of a British medical journal, The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Resistance against Artemisinin actually developed in Southeast Asia around a decade ago. It began after poorly-regulated pharmaceutical companies began selling pills that only contained Artemisinin. The drug itself, while very efficient, only stays in the body for a day or two. As a result, it is often paired with other drugs to allow the effects to stay in the body for a longer period, and take care of any remaining signs of infection.

The largest problem? The potential that this strain of malaria would travel and take over in Africa, which is a highly probable event. This would devastate the continent, and therefore, several experts have already enquired the WHO to declare Southeast Asia's drug-resistance problem as a global emergency.