Author's Note: This is the fourth installment of the series "In The Short Run." (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) John Maynard Keynes, perhaps the most famous economist of the 20th century, famously said, “In the long run, we’re all dead.” The purpose of this series is to propose that in the short run, we are all alive, and economics can teach us to live well.

It matters not what you know, but who you know, or so the old adage says. For as long as humans have lived in community, popularity has had its value. Being popular leads to more connections, which lead to more opportunities. While society sometimes casts a negative light on popularity, claiming seeking favor with mankind is vain, popularity isn’t inherently evil. Having people seek you as a friend, even just a casual one, is an honor and something to be desired.

Many people find becoming popular exhausting, futile and above all confusing, but economics can give insight into how to increase one’s popularity. While asking the “dismal science” how to become popular seems counter-intuitive, it does indeed make sense. For economics at its core is a study of relationships and incentives — two principles popularity is founded upon. So how does economics tell us to become popular? First, we must take a quick lesson on foreign exchange.

Currency exchange is, as the name suggests, a business in which individuals trade different denominations of money. For example, a man might give a woman 10 Chinese Yuan (CNY) for her 1 British Pound (GBP). This transaction would set an exchange rate of 10 CNY is equal to 1 GBP. If another two individuals trade, the exchange rate would adjust.

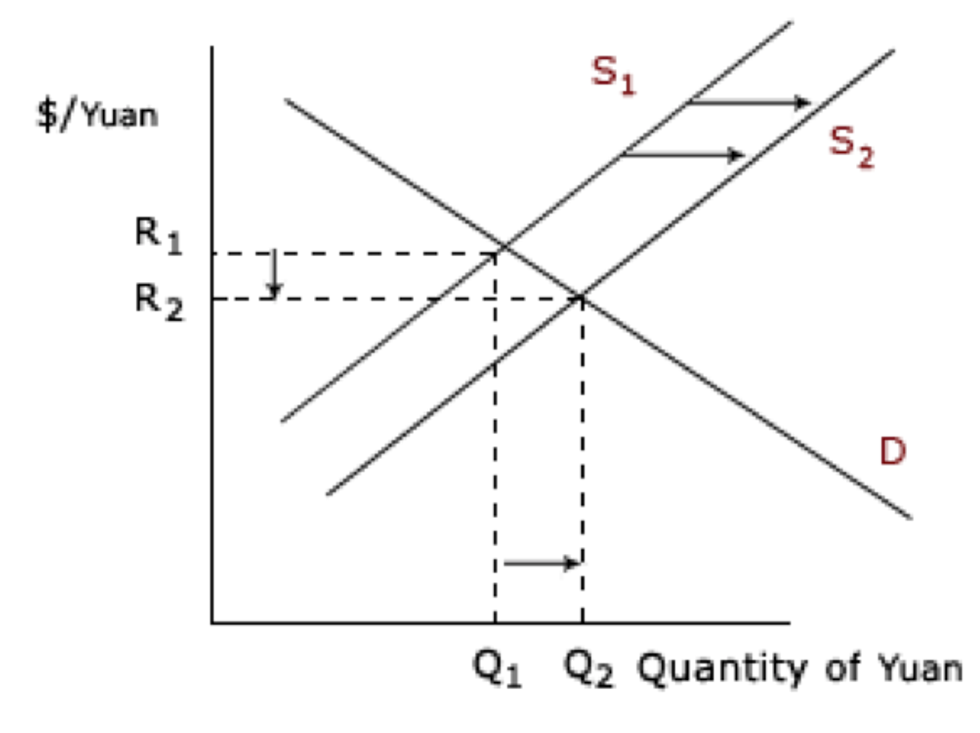

These rates rest on supply and demand. If CNY isn’t wanted, its rate, i.e. value, will fall relative to other currencies. Likewise, if the supply, or amount of CNY in circulation, rises (as shown in the above picture) its value will fall. In the picture, the supply of CNY shifts from S1 to S2. This causes the rate and value of CNY to fall from R1 to R2. The Yuan has decreased in value.

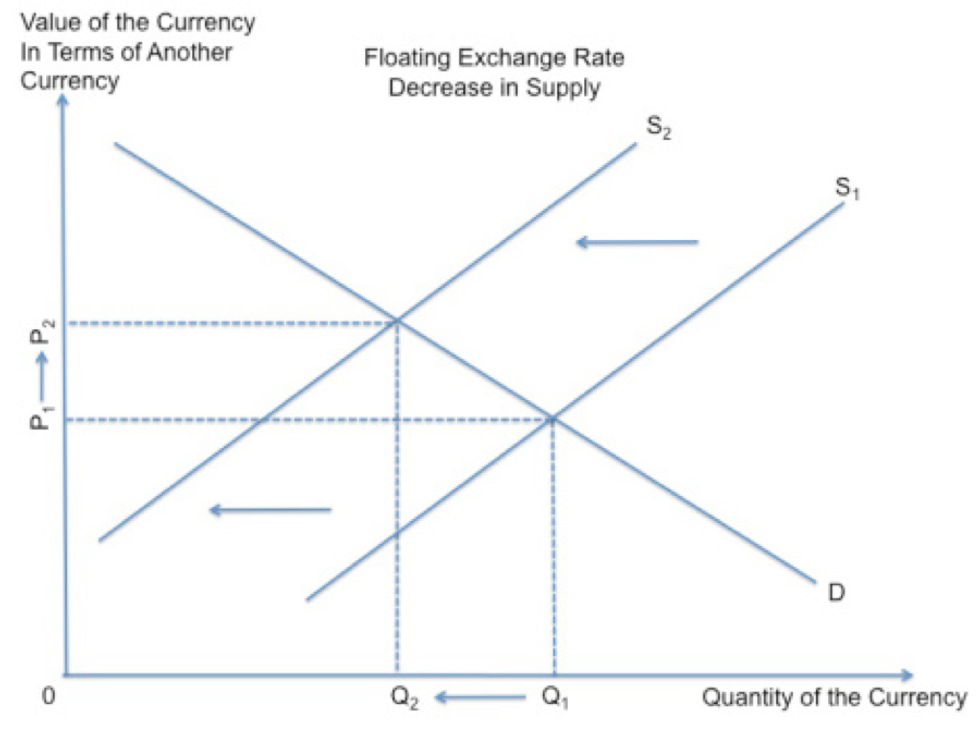

This above picture shows the opposite effect. The supply of CNY has decreased, shifting from S1 to S2. The decreased supply has pushed up the value of CNY, going from P1 to P2. Now, the Yuan is more valuable.

Now, let us circle this back to our original discussion. How do economics and currency exchange inform how to become popular?

Think of yourself as a currency. Your value in relation to others, also known as your popularity, is measured by the Y-axis of a graph similar to the ones above. Ultimately, you can do little to affect or change “demand” for yourself. People will hit it off with you or they won’t, it’s just life. But you can change “supply” of yourself.

Consider your social time to be your supply. This is how much people get to see you and talk with you — their “supply” of you. Much like in the graphs above, limiting or decreasing your “supply” can up your value. People will be left wishing they’d see more of you; they’ll want to know you and seek you out. Increasing your supply has the opposite effect. People who often see you will become exhausted of you, and your value will drop.

Currency exchange does have some caveats. The US dollar (USD) will always be valuable. It’s one of the most secure currencies in the world, and this allows it to keep its value, relatively regardless of supply. Likewise, there are some people that will just be popular. They have that sense that everyone loves, and no one can ever get enough of them. While these robust currencies and people exist, they are rare. For the vast majority of us, tinkering our social “supply” can affect our popularity.

A final thought on this: while comparing foreign exchange rates with human popularity is fascinating and creative, perhaps this could said more succinctly. For I was describing the economics of popularity to my articulate English-major roommate, and he responded quite bluntly and insightfully, “So you’re just playing hard to get.” True, but regardless of what we call it, shrewdly limiting your social interaction can maximize your popularity.