Metrics drive our life’s decisions. To gauge whether to bring a jacket outside, we look at temperature.To determine our academic strength, we follow GPA. To predict our levels of guilt and for how long to use the treadmill, we read calories on food labels. In economics, there is a grand metric, one that determines a country’s economic performance: Gross Domestic Product.

It is a simple concept. GDP measures the value of all the goods and services a country produces. To do so, add up the following:

Spending by consumers

+ spending on goods or services by businesses

+ spending by government

+ exports - imports.

A quick google search finds that the US has a GDP of $16.8 trillion. In other words, the United States produced a total of $16.8 trillion worth of goods and services last year.

But the figure is misleading. GDP is an archaic measurement from a time when the source of our economic productivity was from manufactured goods. It was easier then to measure the amount of tires and refrigerators produced. But today, America’s service-oriented economy makes it nearly impossible to measure the economy.

First, take this trend: over the past decade, US unemployment has declined, but GDP growth has remained dormant. Intuitively, this pattern suggests stagnation in our economy. Yet in reality, America has continued to produce -- not goods, but ideas and services. How would one measure a doctor’s, an investor’s, an accountant’s, a lawyer’s, or a musician’s output? While there are highly complex statistical tricks to do so, they nevertheless fail to capture the breadth of a service’s contribution to an economy.

By definition, productivity is equal to quantity. This means that for services, it is more important to perform more of a service than to do it well, apparently. Thus to improve his country’s economy, a surgeon should focus on performing as many operations as possible in one day -- which intuitively we know will cause more deaths (not accounted for in GDP).

Here’s another paradox. What’s better for the economy? $1 million on computers and schools? Or $1 million spent on of electric chairs and prisons? In the eyes of GDP, there is no difference, it’s simply $1 million added to GDP.

Second, GDP fails to capture the extent of technological advancement. Over the past thirty years, a huge chunk of an economy -- namely, that from information-related industries -- has migrated towards the internet, which poses a mirage of problems for statisticians. Remember, GDP is proficient at measuring “stuff” but not ideas, which suggests that activity from both businesses and entrepreneurs (the engines of an economy) who depend on the internet, will be unaccounted for. While It is clear that the internet has benefited us on a colossal magnitude, the GDP statistic makes us blind to these effects.

Several GDP-related issues have been omitted, such as how reporting agencies have had incentive to mislead (cough, Greece), or how Soviet manufacturers used to put bricks on scales to reach production load quotas -- and avoid being sent to gulag.

So is it time to divorce from GDP? Perhaps economists should look to happiness or environmental sustainability.

Some have proposed as an alternative the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), which is similar to GDP, but it also measures environmental impact. Which means that the more sustainable economic practices are, the more GPI grows.

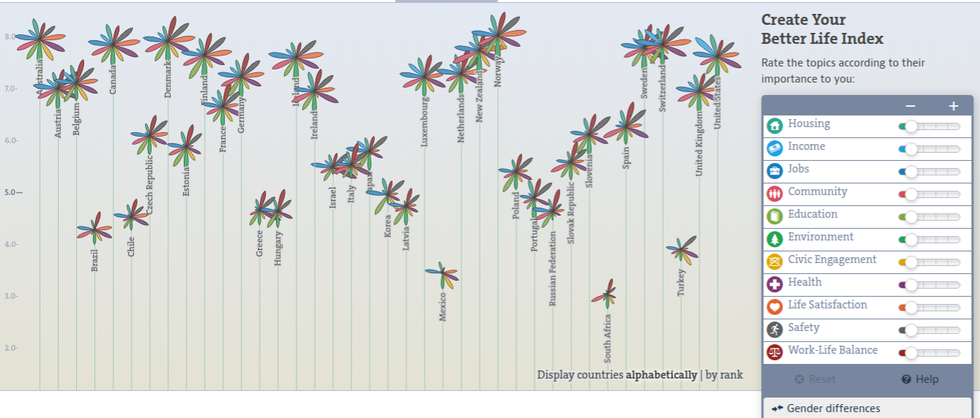

Then there’s the UN Human Development Index -- which uses human health as an indicator for growth -- and the customizable and fun OECD Better LIfe Index -- which allow users to rank countries on well being (i.e., work-life balance, Income, housing, and even gender equality).

But “happiness” and “welfare” are abstract and philosophical concepts, national income and economic output are not. In addition, alternatives such as GPI are biased towards a certain ideology, making them less objective and less straight-forward than GDP. In pluralistic economies and societies, these metrics fail to capture the economy -- GDP does a slightly better job.

And one cannot conduct monetary or fiscal policy in the absence of GDP. Imagine investors purchasing bonds of a foreign government on the basis that people are civically engaged (some would -- I don’t doubt it). It would be as if a pilot determined cabin pressure levels based on passenger satisfaction as opposed to altitude.

So don't abolish GDP. The next steps are to continue to improve accounting standards, establish a standardized method of measurement, and to educate the public about GDP's shortcomings.

Let us be clear that, unlike a thermometer which measures temperature or a speedometer that measures speed, GDP is a man-made construct that postulates on what it means to be productive and associates itself to a set of facts. It doesn’t indicate the quality of goods or services nor does it measure happiness. GDP has some wonderful alternatives, but they aren’t great economic yardsticks.

In short, GDP is like Beyonce: it’s a powerful thing with a lot of followers, one has to be careful around it, it has a lot of excellent competitors, but it will forever remain queen of economic analysis.Note: Beyonce's artistic contributions are not accounted for in GDP.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion