I spent a good part of my undergraduate career doing research on the lives of Black men. Prior to this, focusing on the lives of Black men and boys was something seen as obsolete and often overlooked. My introduction to the subject came my sophomore year when I was on the university library database conducting research for a history project. By typing the words "African American men," an article from "The West Journal of Black Studies" titled "God Bless the Child Who Got His Own: Toward a Comprehensive Theory for African-American Boys and Men" appeared. I was sold.

In the world of academic research, Black masculinity is largely still under researched. When I began to do this research, much of my motivation didn’t come from the books of the scholars but rather the Black men in my own life.

I used to think the experiences of Black men didn’t have no academic merit. I rarely saw academic scholars that looked like me that studied my experiences. I used to think relationships I had with other Black men such as my father and grandfather were something only unique to me. It brought me great comfort to find that research had been done for decades to discover the intersected tension living in our experiences stands long before the test of time.

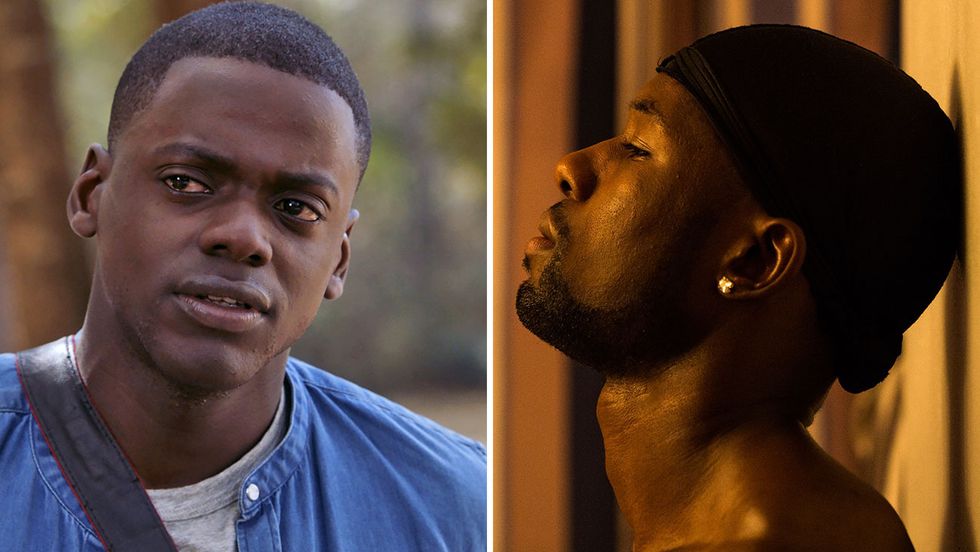

Black masculinity has made a transition today. Scholars of the future will note a rather unprecedented portrait of the Black male. From Barack Obama’s historical presidency to the historical Oscar win for the 2016 Black LGBTQ film Moonlight, Black men are becoming more and more multi-faceted. Accompanying this, a dialogue is being had fueled by the occurrences in the media surrounding mass incarceration, racial profiling, and #BlackBoyJoy, in which many young Black men coming of age are beginning to reject prospects and principles in the time of our fathers and grandfathers in favor of adopting a more organic sense of manhood.

Gone are the Cliff Huxtables and the Magic Johnsons of the 20th Century, Black men today have more choices and are in more avenues than many would have ever imagined decades prior. Despite the effect of what sociologist Arlie Hochschild calls a “stalled revolution” in which despite progress being both demonstrative and delayed, efforts are being made both in the academic and non-academic sector to preserve the work of the historical Black men as well as welcome the work of Black men of today.

In the realm of popular culture, film and television is coming into a new arena with the arrival of director Jordan Peele and his 2017 box office hit Get Out as well as the exclusive Netflix series Dear White People. Black boys have more choices and more expectations than to become the next Magic Johnson or Michael Jordan or even the next Jay Z. Black men have long been steered away from career paths that capitalize on them utilizing both their critical and creative skills to their full potential. Now, in the era of Millennial optimism, a space has been created, cushioned in cultural tension surrounding race and gender, where Black men adopting this multi-faceted Black masculinity is no longer an option but rather necessary.

Unfortunately, America is still plagued by age-old racial rhetorical monsters that perpetuate old stereotypes such as gang violence and the Black male phallus as a symbol of danger and destruction. The innovative work done by the Black men of today will no extinguish these stereotypes from existing but rather deconstruct and discredit them.