Today, women like Serena Williams, Ronda Rousey, Danica Patrick and even Condoleeza Rice dominate the world of sports. With their powerful physique and killer drives, very few can even hold a torch to these women who have set ablaze the path of women in athletics. However, very few know the story of how the path came to be paved in the first place. With feminism ever on the rise in our world today, it’s easy to forget that there was once a time where a long distance run for a women was no more than two miles or that a female in the weight room was entirely unheard of and frowned upon.

Kris Miller, eight time World Duathlon Championship runner and silver medalist for the National Triathlon Championships, was part of the Title IX generation of female athletes in Minnesota and knows first-hand the struggle of a woman trying to make it in a man’s world of sports. “A lot of young girls do not know what Title IX is and don’t appreciate that they can play sports,” said Miller. “You don’t want it to be taken for granted and forget that women really had to fight for the right to play.” Title IX was issued in the 70s when Congress passed the Educational Amendments. Title IX was one section of these amendments which prohibited discrimination against girls and women in federally-funded education systems, including the athletic programs. However, a female athlete’s opportunities were highly limited prior to 1972 and as Miller stated, it was a fight for women to gain the right to play.

Miller has been a runner all her life and is passionate about the joy the sport has brought her. On the track field of Derham Hall high school, a young teenage Miller began her journey as a widely successful female runner. “A half mile, mile and two mile were considered for females long distance events in my high school,” said Miller. “It was believed that if a girl were to exercise too much or over exert herself, she would not be able to get her period and thus could not produce babies.” Miller explains that at that time, a woman’s primary value was founded on her ability to have children and care for her family. Any other activities she participated in were considered minor hobbies and were rarely taken seriously. “My mom was a big enforcer of these false women ideals,” said Miller. “Around age 12 or 13 I wanted to start lifting weights and my mom said that women aren’t supposed to lift weights because you don’t want to end up looking like a man.” However, this didn’t stop Miller from reaching her goal. At age 14 Miller turned her basement into her own gym and used bicycle inner tubes to make resistance bands for herself. Miller’s father even took her to a department store to buy her a weight set. “My dad supported me in ways I didn’t know at the time,” said Miller. “To this day, I’m thankful he got out of the way and let me go on to more than what society had laid out for me.

In her effort continuing to combat the negative view of women in sports, Miller participated in as many track events in high school as she could competing in the two mile long distance runs eventually racing in state championships holding the conference record for the two mile long distance run. “My friends and I would have medal counts and compete to see who could earn the most,” said Miller. “My friends often won the contest since they would compete in the short distance runs and were allowed to do many of those while I was only allowed to compete in one of my long distance events. It was entirely unfair.” Miller did eventually make it into her high school athletic hall of fame but not until 2012 when the hall of fame was first established. “Derham asked for my athletic resume of what I had done since high school,” said Miller. “I was one of the first to be put in the hall of fame.”

Miller went on to attend the University of Minnesota in 1980, a few years after Title IX had already passed. However, the notion was not completely enacted. Soon after Title IX was issued, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) complained that boys' sports would suffer if girls' sports were to be funded equally. Regulations about how to enforce the law were not released until two years later and did not go into effect until 1975. Still, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, did not enforce these regulations for securing Title IX rules in colleges and high schools. The enforcement of Title IX came to a screeching halt. In 1984 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Title IX only applied to programs directly receiving federal funds. Other programs, such as athletics, that did not receive federal funds, were free to discriminate on the basis of gender.

“More money was spent on men’s sports than women’s,” said Miller. “Women athletics received far less financial support from the university and we had to continue to prove we belonged on the same field as men.” Miller joined the U of M track team as a college freshman, racing in indoor 5k and 10k events. Though the change was small at first, eventually things began to change for women athletes. The women could run longer distances, obtain athletic scholarships and were even encouraged to lift weights. “One of my personal favorite changes was that our college finally built a women’s weight room after Title IX,” said Miller. “Before we had to share with the boys. It was the smelliest place on earth, not to mention we weren’t particularly welcomed there.” The growth in women’s sports also began to offset the numbers for men’s sports, causing more equality in numbers and dollars.

Four years later, after women’s rights groups began to fight back, Congress passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988, outlawing sex discrimination throughout the entire educational institution regardless of which programs received federal funding. In addition, the OCR renewed its commitment to ending gender discrimination, calling Title IX a "top priority," and published a "Title IX Athletic Investigator's Manual" to strengthen enforcement procedures. This allowed for women athletes like Kris Miller to run just as far as male athletes and compete alongside them. Eventually opportunities became equal for everyone. But Title IX had more positive repercussions with female athletes than just being able to run a marathon. “Women became less likely to do drugs, get pregnant or drop out of school,” said Miller. “Title IX told us that we could do more and achieve anything we wanted. It was liberating.”

Since graduating from college, Miller has gone on to win both National and World Duathlon and Triathlon Championships, was named Amateur Duathlete of the year as well as Female Athlete of the year in 1996. Miller even taught herself along with a team of women to row winning gold medals in World, National and European Championships. “Before Title IX, girls were considered extremely delicate and if you were good in sports you were assumed to be a lesbian,” said Miller. “While the men ran their big-time marathons we ran our Mini 10ks. Now, we see women being the top finishers in marathons and going to the Olympics. Title IX completely changed the way women were viewed in the world of athletics.” Though the world of sports has drastically changed for women, people continue to forget how long it took to get here. The courage of women activists and athletes to take a stand was no minor act and it has given girls and women of all ages the freedom to play. “It surprises me how many people think I wasn’t effected by athletic discrimination because of the success I’ve had in my athletic career,” said Miller. “We tend clump Title IX with a lot of cultural shifts such as women gaining the right to vote. That sort of thing has just become the norm for us now. We as women are so used to voting, playing whatever sport we want, having high positions in government that we’ve forgotten how many women had to fight for our right to do so.”

At age 54, Miller continues to live for the thrill of the starting line. As a 19 year member and grand master, Miller still competes in races for the St. Paul based Run ‘n Fun Racing team. “I think it’s fantastic that glorified women runners are an everyday occurrence,” said Miller, “But we should keep reminding people why it is so fantastic. You don’t want to forget your roots. I am honored to have been part of the Title IX revolution.” With every step she takes in her athletic career and with every line she conquers, Miller makes a point to never forget the battle that brought her the success she shares today and the experiences that have made her stronger and more determined as an athlete. “We all need to be grateful for the people who paved the way before us and keep pushing limits and never take no for an answer,” said Miller. “We each pave the way for someone coming behind us. We are part of a continuum whether we want to be or not.”

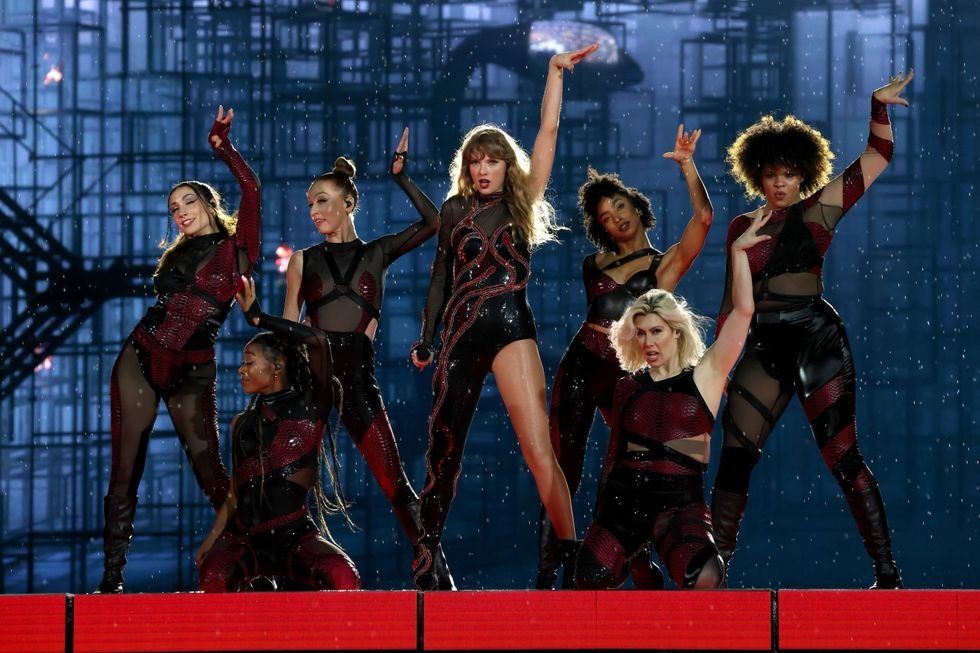

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.