In regards to an argument, or the process that is oratory writing, the two essentials are strategy and structure. My previous article had further defined these two elements as conditions involving a more prominent pursuit. Again, it is the search for meaning as well as the endeavor for clarity. For the purposes of this article in particular, I will explore this concept of lucidity specifically in regards to literary writing.

If I am to begin anywhere, though, it would be with the Romantics. Lord Byron, or George Gordon Byron, was a passionate man and poet. His work in particular is a great example of clarity being used in terms of simplicity. During the Romantic period, there was a keen fascination with ‘order.’ Or, more specifically, patterns and rhythm. Poetry is music without sound, whether it is read silently or not, it will always have a certain rhythm. Take note of this first paragraph in Lord Byron’s “And Thou art Dead, as Young and Fair.”

And thou art dead, as young and fair

As aught of mortal birth;

And form so soft, and charms so rare,

Too soon return'd to Earth!

Though Earth receiv'd them in her bed,

And o'er the spot the crowd may tread

In carelessness or mirth,

There is an eye which could not brook

A moment on that grave to look.

Notice the subtle use of rhyming that varies throughout—it is written as if read; it is written to affect how you read and how you process the written word. Just as spoken language is only clear with silence, poetry presents its lucidity with rhythm and rhyme. This is the poet’s way to draw your attention to a particular ‘something.’ For instance, the first four lines present a distinct pattern: “As young and fair” parallels with “and charms to rare;” while “as aunt of mortal birth” directly aligns with “too soon return’d to Earth!”

Though this seems facile at first, it clearly expresses the intent of the poet. Again, Byron is drawing your attention through the perception of simplicity. His intent is clear, and therefore you read on; you read on in pursuit of the meaning. And though it is presented as simple and straightforward, it becomes a complex puzzle to define and redefine the meaning behind what’s in front of you. In the end, it is a process meant to be ever unfinished. Poetry, in many ways, is the analysis of the human mind—the study of purpose. Another writer that dived into this discussion of psyche was the immortal children’s author Dr. Seuss.

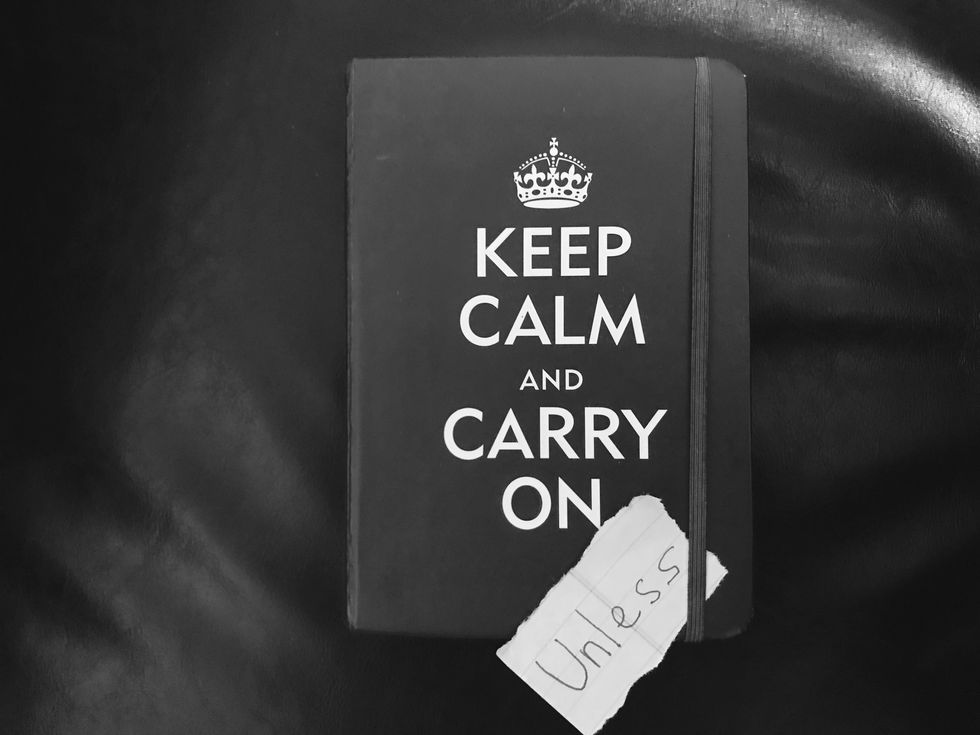

Again, with the use of simplicity, Seuss creates stories of far away places, with strange new faces, along with strange phrases that sadly don’t fit in our English language. Many of his stories featured seemingly obvious messages that became timeless as well as versatile. His stories remain just as (or more so) entertaining as when we were children. Why? This, again, is partially due to the correlation between simplicity and clarity. The stories told are drawn for children, therefore the goals and plot points are laid out clearly and (perhaps) plainly; however, due to the simplicity and more importantly openness, room is given for every reader to think. While Byron draws you to reflect through organized rhyme scheme, Seuss encourages you to process through the space. Like I said in my previous article, silence is key to public speaking because it allows the audience to think and fully understand what’s being said. Dr. Seuss uses the same process except with space. He lays out the overall message of his books, while allowing you, the reader, to fill in the discussion. A good quote to exemplify this would be from his famous book The Lorax—primarily, the renowned line:

“‘But now,’ says the Once-ler, ‘now that you're here, the word of the Lorax seems perfectly clear. UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It's not.’”

Now as part III of my discussion comes to a close, I ask you to explain your cons and your pros.

I’ve brought up some topics—just tools to use.

Now it’s up to you to finally choose.

To choose to agree or not—or neither.

Great even! If you can write in kind.

Byron and Seuss, opposites to account.

Both shared expression—both held doubt.

I ask you, how long will you pine,

until it comes time to speak your mind.

Unless, unless, screams awfully true—

For it’s time to fulfill that space.

Take what you read, share what you know—

It’s time, to explore, who are you?

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion