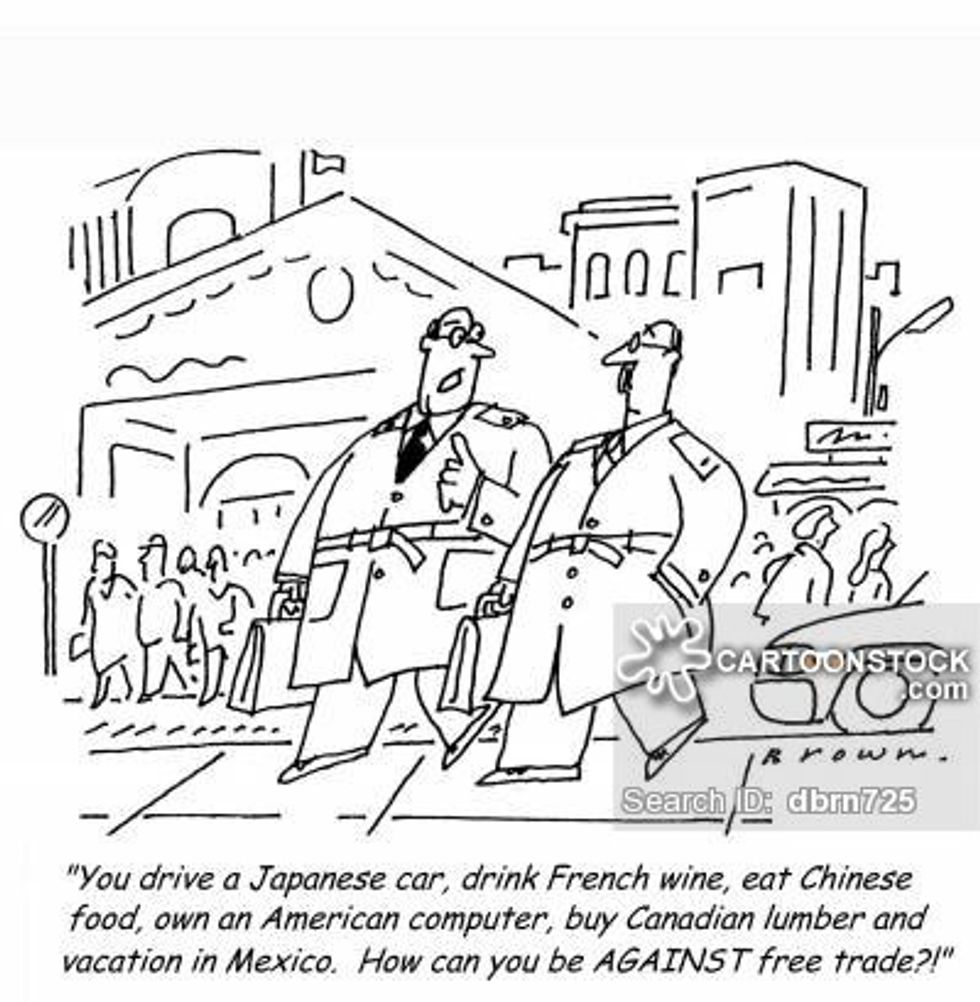

On November 15, 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) the “gold standard” of free trade agreements. In 2015, the text of the TPP was revealed to the public, after years of secret negotiation. That same year, Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign, unleashing a populist movement that taps into a fear and one-sided misconstruction of free trade. Hillary Clinton said she was against the TPP shortly after. In the midst of all this, the Obama administration remains furiously at work behind the scenes trying to pass the TPP and secure its last major foreign policy initiative. How do all these events connect? Why is free trade such a big deal now? What is free trade anyway?

Well Mary Sue, I’m glad you asked. Free trade simply refers to the import and export of goods among countries without any kind of barrier imposed on the goods. Such barriers include tariffs, levies, and quotas that determine how much of a good from another country can enter a domestic market and whether the exporter needs to pay a tax for selling goods abroad. Countries have historically enacted these barriers so that domestic industries face less competition from abroad. Exporters that wish to sell a good in another country have historically paid a fee for doing business in that country, usually in the form of a tariff, which is a kind of tax. This cost is paid at the time of shipping and then passed onto the consumer in the form of higher prices. If a good produced abroad is more expensive than a similar good produced domestically, the consumer is inclined to buy the domestic version. In fact, the consumer is almost always inclined to buy the cheaper of two of the same good, assuming that the quality of each is comparable. Therefore, in order to protect domestic industries, governments have often favored barriers to trade. This has broad implications on the development (and stagnation) of local industries and employment levels.

Recommended for you

Higher barriers to trade impede the flow of goods that travel throughout the world. Barriers increase the cost of doing business in other countries and typically discourage producers in one country to sell in other countries. This is good for domestic industries. If companies don’t need to worry about competition that can produce the same good at a cheaper and more efficient rate, then those companies face less pressure. This applies specifically to competition from abroad. If lumber producers in the U.S. do not need to worry about lumber producers from Canada that can provide comparable goods to U.S. consumers at cheaper rates, then the American lumber industry can remain relevant. This is good news for all the companies and workers in the U.S. lumber industry, including associated industries, such as furniture producers. As such, they would favor barriers to trade in Canadian lumber.

Assuming that the quality of lumber from Canada is comparable with that of the U.S., consumers are inclined to purchase the cheaper of the two. In this context, tariffs are a government-sanctioned method of distorting the price of the imported lumber. The government actively engages in favoritism towards domestically produced goods to protect those the lumber industry. While this is good for American lumber workers, it has other ramifications. If the price of Canadian lumber would be cheaper without tariffs, then U.S. consumers would not be artificially guided to one product over the other. They would simply choose the more competitive good.

There are several reasons as to why one good from abroad might be cheaper than a comparable one produced locally. Most often, it is because of cheaper labor costs. It could also be geographical and climate reasons. Saudi Arabia is better than Brazil at producing oil. Ghana is better than Sweden at growing cocoa beans. Chile is better than Japan at digging up copper. These factors are largely outside of any government’s control. Sometimes, however, a government makes strategic policies to encourage the development of different industries. Taiwan, for example, is really good at producing semiconductors, which are tiny processors found in almost all electronics, from phones to TVs. Research and development (R&D) spending there totaled 483.5 billion Taiwanese dollars, or 3% of GDP. The biggest spenders were electronic component makers, such as semiconductor producers. South Korea is a hub of consumer electronics, and is home to firms such as Samsung, LG, and SK Hynix (a chipmaker). In one generation, South Korea has transformed from a rural, agrarian society to one of the most robust, technologically forward countries in the world, largely thanks to government policies that enabled the development of various industries. What a country is good at producing can be the result of several factors. Some countries are better than others at producing certain goods. Tariffs distort this reality by favoring one local industry over a foreign one, regardless of which country is better at that industry.

Raw resources are often incorporated into more complex products that are then shipped the world over. International trade allows countries to produce what they are good at and integrate it into a wider system to make sophisticated products. Take an iPhone. It’s made out of several parts to make one final product that we all love (but Androids are better). LCD screens are made of aluminum and silicon. China is the leading producer of both, while Russia and the U.S. second production in aluminum and silicon respectively. Lithium-ion batteries are made of lithium, manganese, cobalt, and a bunch of other minerals you learned in eighth grade. Australia, Chile, and China are some of the leading producers of lithium. Microchips that act as processors consist of tiny amounts of metal, such as gold, silver, and copper, many of which come from African countries. The amount of resources needed for an individual smartphone is insignificant. Now consider 2.5 billion, the number of smartphone users projected for 2019, many of whom may own more than one smartphone. Now consider the number of TVs, tablets, PCs, laptops, gaming consoles, and other consumer electronics that people own all over the world. Producing the goods we take for granted is only possible because countries engage in an intricate web of commerce through which resources are traded. But this applies to all industries, not just consumer electronics.

Both cartoons have their merits

Barriers to trade distort this reality. They actively impede the flow of goods to maintain a status quo that is beneficial for a domestic industry. Workers in a local industry usually favor such barriers, but they can cause more harm than good in the aggregate by limiting choices for consumers. For the past few decades, however, it has been the official policy of all U.S. government administrations to remove barriers to trade. This can be traced back to the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Free trade agreements (FTAs) are agreements among countries to categorically remove barriers, such as tariffs, quotas, and levies. Each FTA is unique, and countries negotiate what kind of barriers to eliminate, depending on their own situations. Some industries are powerful enough to lobby for the maintenance of barriers to protect their own interests: the U.S. agricultural industry is an excellent example of this. Other barriers are eliminated altogether. Some barriers are phased out over time, to provide a buffer period for local industries to adjust to foreign competition. Nevertheless, FTAs are a means of making trade more seamless among countries, ultimately aiming to increase trade and overall economic activity. It is officially the mandate of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to eliminate trade barriers through multilateral negotiations. The last set of talks, known as the Doha Round, experienced a breakdown years ago because of disagreements between India and China and developed countries over tariffs on agricultural products. The Doha Round never went anywhere and the WTO has done a whole lot of nothing ever since. FTAs have emerged as an alternative. They are a way of achieving the same goal outside of the WTO, usually with a group of countries in the same region. NAFTA is an early example of this trend.

Passed in 1994, NAFTA opened the U.S., Canada, and Mexico to greater trade relations with each other. By eliminating barriers and enabling the free exchange of goods, our three countries are more economically intertwined than ever before. This has led to a lot of economic opportunity. Many U.S. firms that once manufactured domestically have offshored their labor operations to countries where labor is cheaper. This is good for their bottom line, which is usually reflected to the consumer in the form of lower prices for goods. Things that used to be produced in the U.S. en masse, like consumer electronics, clothing, footwear, furniture, toys, and more, are now primarily manufactured in developing countries where labor is much cheaper than it is in the U.S. FTAs like NAFTA facilitate this change.

With the promise of relaxed border controls in relation to economic activity, free trade makes it easier for companies to switch manufacturing operations to other countries. This directly contributes to the loss of good-paying manufacturing jobs for Americans. These displaced Americans are often left holding the bag, taking on jobs that do not pay as well and are often less secure than manufacturing jobs. Meanwhile, the leadership of private sector companies, lovingly known as corporate America, lines its pockets. By offshoring labor and capitalizing on the reduction of barriers to trade, and given low transportation costs, companies maximize profits. In a capitalist economy, profit accumulation is the holy grail of economic activity, even if it not always clear why profits are being accumulated to begin with. Free trade does in fact play a role in the gross inequality of our country. With globalization, that dynamic is being played out across the world.

Free trade, however, has done enormous good. It provides consumers with greater choices that are usually cheaper than the alternative. It also brings countries closer together economically. This benefit is hard to overstate. Economic activity between countries engaged in an FTA usually goes up: this increases investments, encourages mutual prosperity, and helps to develop industries in poor countries that would otherwise not be developed. There is also an argument that free trade leads to a more peaceful world: nations are less likely to go to war if they depend on each other for trade. Free trade is also not solely responsible for the state of our current economy. Labor is offshored for several reasons and many economists argue that manufacturing labor would have been offshored to low-wage countries with or without NAFTA. In this analysis, NAFTA simply facilitated the inevitable, rather than caused it.

Several FTAs have been enacted since NAFTA. While FTAs have promoted certain economic interests in the world and done good in the aggregate of a global economy, they have also caused harm to workers in developed countries who lose their jobs and workers in underdeveloped countries who are often unprotected. Free trade is a multifaceted issue that cannot be dismissed in a sound bite or a tweet. It requires thoughtful analysis to discern. The Trans-Pacific Partnership is another major FTA, perhaps the biggest one in a generation. If passed, it will have enormous ramifications throughout the world. But we'll talk about that next week.