I had just crossed the state line, some roadside billboards containing images of a white Jesus, and others containing signs notifying drivers and passengers alike that a fetal heartbeat begins three weeks after conception, the usual indication that I was driving through North Florida. Being that I was riding passenger seat during this leg, I had turned into a typical millennial, logging onto Facebook to check the news. Facebook. At any rate, I saw that Fidel Castro was trending, and upon inquiring further, I read that the former Cuban leader was pronounced dead at ninety years old the day before. Upon announcing the news out loud, I made eye contact with my grandmother through the rear-view mirror, who paused for a second, then simply replied, “Dammit… And before I got to go to Cuba.”

Between the mixed reactions I perceived, from those on social media that were of a celebratory tone, mostly coming from people I knew in the Miami area, to the more somber reaction of my grandmother, a generally politically conscious woman of Afro-Cuban descent, I decided to further investigate the complicated character of Fidel Castro, particularly the fascination with Castro that black people specifically seem to have with the late dictator.

Black America’s love affair with Castro is best described as…complicated, at the very least. While black Americans are generally exposed to just as much propaganda and political rhetoric as the rest of the country, we generally have the tendency to be more critical of certain things, due to a history of not being able to trust the system for obvious reasons. That is to say this: Though we are primarily American in our culture and political ideals, part of the reason the image of Fidel Castro resonates so well with Black America as opposed to others, is because of our shared history of the oppressive implications of colonialism.

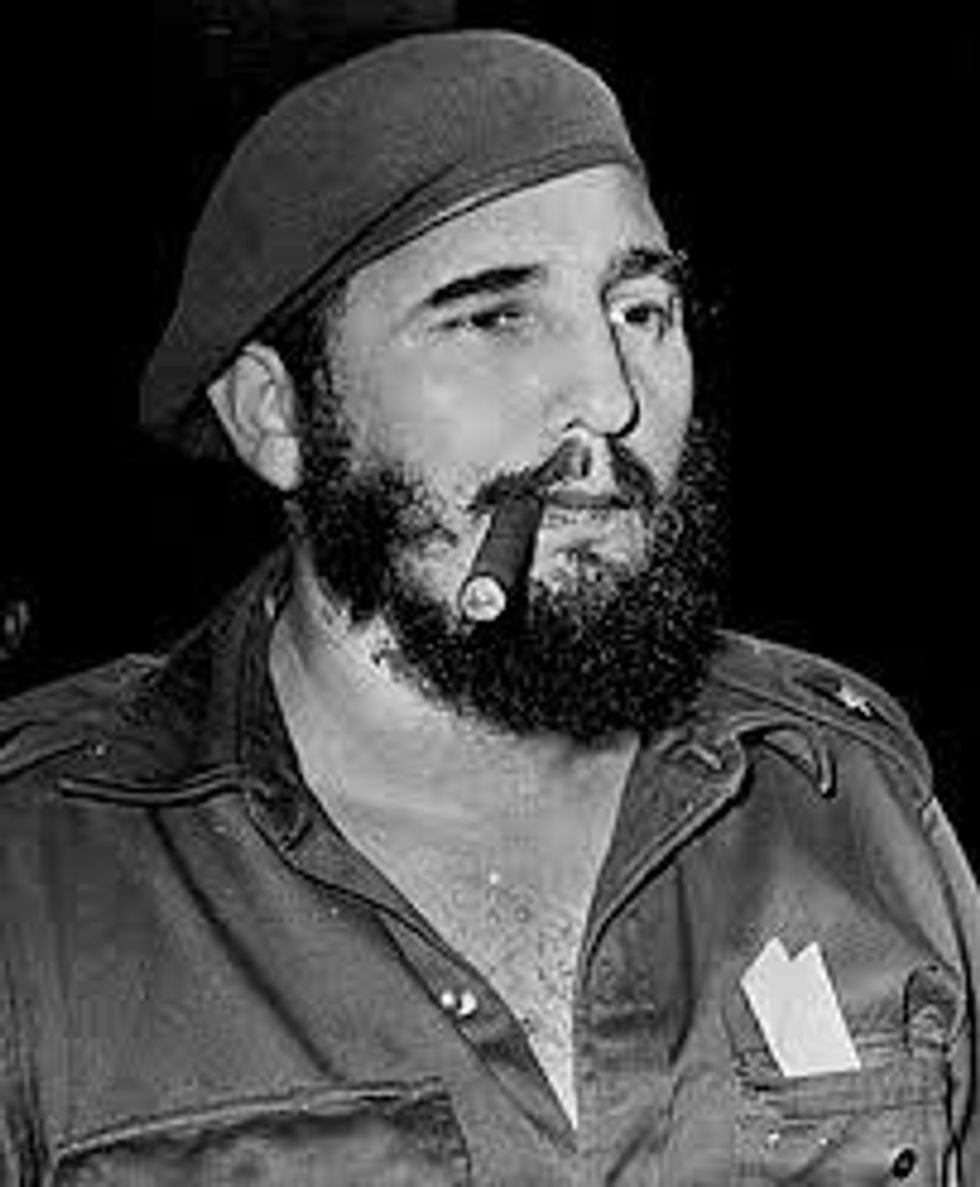

After quarrelling with his father over his exploitation of Haitian sugarcane workers as a child, Fidel was sent away to school, where he was often reprimanded for his misbehavior, a characteristic indicative of his rebellious tendencies that would persist throughout his educational career. In college, his anti-authority sentiments flourished, with Fidel becoming involved in the gang and freedom-fighter cultures that stood against imperialism and the exploitation of small Caribbean countries by Western powers, particularly the U.S.

As people who, historically speaking, have been victimized directly and indirectly as a result of Western colonialism, Black America resonates with this aspect of Castro, seeing him as somebody who took a stand against Western powers in favor of the underdog, despite the fact his family’s wealth could be attributed to the exploitation of poorer people by the West. To black people, Castro used his privilege as a platform to fight for those without a voice, a quality we haven’t seen much of in American politics or general American culture at all.

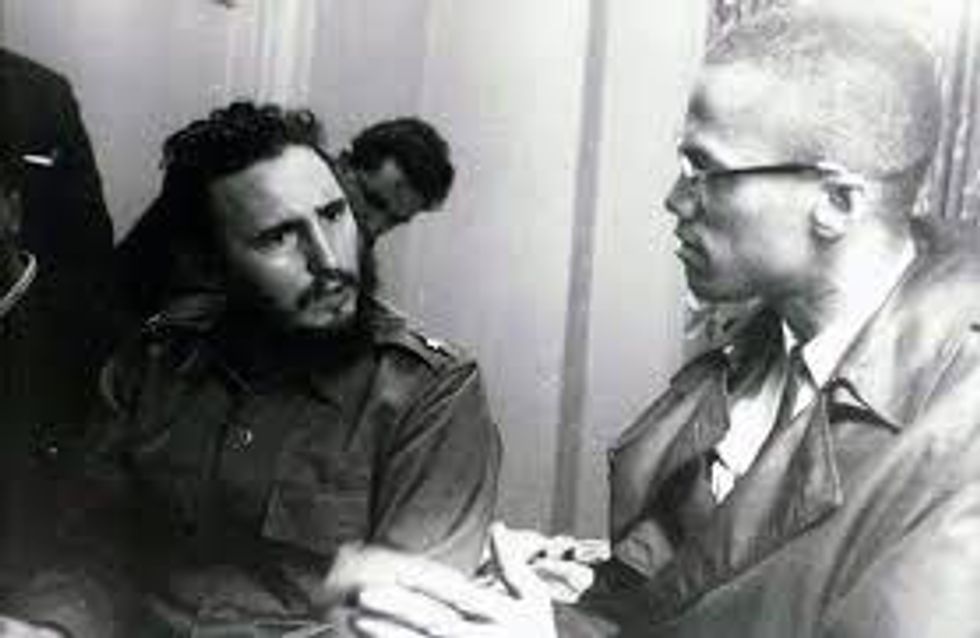

Perhaps what first brought Black America’s attention to Castro was his visit to Harlem in 1960. While initially meant to stay in Midtown, Manhattan for a United Nations General Assembly meeting, Castro and his entourage felt insulted by his initial hotel’s management, and sought another place to stay, Eventually ending up in Harlem’s famous Hotel Theresa, a black owned establishment, where he eventually met and conversed with Malcolm X, finding common ground with the activist on several issues. This also marked the first time that a foreign leader had ever happily lodged in Harlem, and with hundreds of black people gathered outside of the hotel cheering the arrival of Castro and his entourage, the Cuban leader waved to the people in what Malcolm X would later call, “a psychological coup over the U.S. State Department when it confined him to Manhattan, never dreaming that he’d stay uptown in Harlem and make such an impression among the Negroes.”

Of course, as signified by Donald Trump’s shouting out of “his African-American” at a rally (he wanted to say, “That’s my nigga,” so badly) and Hillary Clinton’s embarrassing Whip and Nae Nae debauchery on the Ellen DeGeneres Show, Castro’s stay in Harlem wasn’t the first or last time a politician tried to appeal to black people for political reasons. However, unlike what has been seen in many American political situations, Castro made many attempts at helping black people, not only in the U.S. and Cuba, but also in other places around the world.

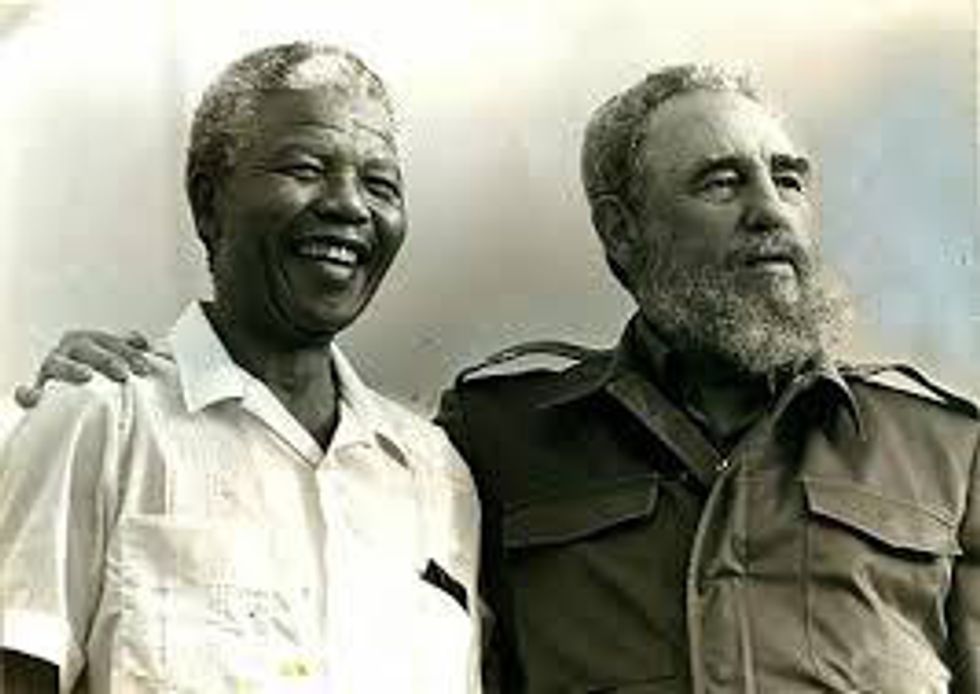

From granting political asylum to a number of black freedom-fighters, most notably Black Panther and Black Liberation Army associate Assata Shakur, to aiding in military interventions in Angola against U.S. backed, apartheid supporting regimes, to his parallels with, and admiration by Nelson Mandela, Castro has shown himself to be an ally of black people in a way that no American politician ever has been, especially in considering that there is still a bounty on Assata Shakur, and that Ronald Reagan, a president praised by conservatives and hated by people of color alike, vetoed the Anti-Apartheid Act. While Fidel Castro was obviously not perfect, black Americans perhaps more completely understand the hypocrisy of praising people like Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton, Che Guevara, and others, while simultaneously condemning Castro.

For the sake of fairness it is important to not be misleading. We know that Castro, just like any other politician (and perhaps even more so), is not a beacon of morality. Especially when taking into consideration the people affected by his policies, there is a significant amount of reconciliation to be done in favor of the Cuban American people displaced by Castro’s long dictatorship. However, in terms of efforts extended toward marginalized people, especially those poorer and of a darker hue, Castro symbolized a type of politician almost unprecedented in modern history as one who was not only able to relate to people outside of his own demographic through the shared experience of pain and oppression, but tried, at least in part, to change it.