This week, Republicans and the president have failed to get the American Health Care Act through Congress. The act would have stripped 24 million Americans of their health insurance, which they gained under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). However, regardless of whether or not the ACA gets repealed, a large group of Asian Americans do not -- and might not -- have equal health care access to begin with. The following is a multi-part series on California Assembly Bill 1726, a piece of legislation that passed in September that might allow greater health care coverage for Asian Americans in California.

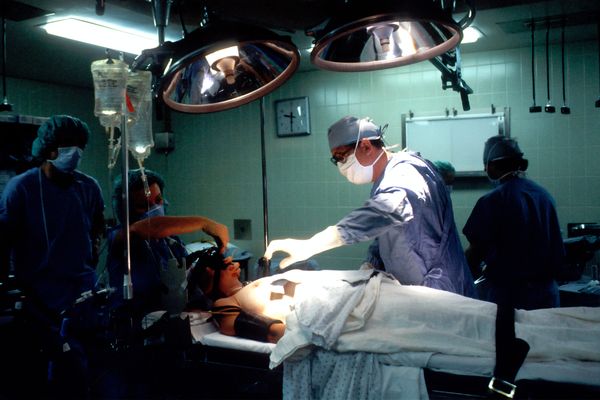

In 1997, journalist Anne Fadiman published her book, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures. Fadiman explored the cultural differences between Hmong ritualistic medicine and Western peer-reviewed medicine through the real-life case of Lia Lee. Lee, a Hmong infant who immigrated to the United States with her parents to Merced, CA in 1980, was diagnosed with epilepsy as a toddler. In The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, Fadiman explores how the doctors at Merced Community Medical Center (MCMC) turned a blind eye to traditional Hmong healing practices such as shamanism and ancient herbal remedies in favor of Western practices. Lee’s parents responded by turning their backs on Western medicine when their daughter’s condition failed to improve. A Hmong-English language barrier further exhausted the relationship between the Lees and her Merced-based doctors. In the end, Lee suffered a brain death and remained in a vegetative state until her death in 2012. The book, which Fadiman meant as a lesson for cultural competence, is assigned reading for many aspiring health and medical professionals.

Yet, 19 years after its publishing, the quality of life between Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (APIs) and the West could still be as stark. For example, East Asians are at a higher risk at Hepatitis B compared to Indian Americans according to a study by the CDC. Korean academic achievement stands to be much higher than Filipino academic achievement. Pacific Islanders are much less likely to achieve a four-year degree than Asian groups. The Hmong have a 26 percent national poverty rate from 2007 to 2009 – the highest among any API ethnic group in that time period. In California, between 2006 and 2010, the Mongolian poverty rate is more than twice the California average. 40 percent of Hmong Americans, 38 percent of Laotian Americans and 35 percent of Cambodian Americans across the country drop out of high school. Only 14 percent of Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians nationally over the age of 25 hold a bachelor’s degree.

All these ethnicities are all identified in California state-run data collection as “Asian.” The same goes for Chinese Americans, Korean Americans, Indian Americans, Vietnamese Americans and 18 other ethnic groups as recognized by the United States government. Pacific Islanders are identified under their own catch-all category: Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian. That’s despite all these communities’ vast differences in health care and education access between them. All data from all Asian and Pacific Islander (API) ethnic groups are lumped, or aggregated into the categories one of these two categories.

Although a bill, California Assembly Bill 1088, was passed in 2011 to disaggregate, or separate and compartmentalize data into ethnic categories among APIs to help better evaluate these disparities, the requirement to disaggregate data only applied to the California Department Fair Employment of Housing and the California Department of Industrial Relations. Such a bill had not yet reached the realms of health care or education.

So after some thinking, California Assemblyman Rob Bonta decided to do something about it.

Bonta serves as an assemblyman in the California Legislature from the 18th district, a position he has held since 2012. He is the first Filipino American to be elected to the Assembly. Bonta is the key author of California Assembly Bill 1726 (AB-1726), officially known as the Accounting for Health and Education in API Demographics (AHEAD) Act. AB-1726 is the culmination of a long fight to disaggregate Asian American and Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian data into certain subgroups mostly based on ethnicity. Such subgroups would include, but would not be limited to, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, Indian, Laotian and Cambodian. The bill also hoped to add different ethnic groups to disaggregate such as Bangladeshi, Hmong, Indonesian, Malaysian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Taiwanese and Thai. The Assemblyperson is all too familiar with data disaggregation. His fight for such legislation began with a very similar bill, California Assembly Bill 176 (AB-176).

Look for the next parts of this feature in the coming weeks.