The first time I heard Tracy Chapman’s song “Fast Car,” the main thing to hit me was the beautiful, catchy guitar intro. With another listen it was absolutely clear why this song had become a pop classic. It took me a few more listens to really dig into the lyrics, and what I discovered startled me.

The first stanza depicts a desperate situation where there’s “nothing to lose” and that “any [other] place” would be better than. The second stanza tells of a plan to “get us out of here” by driving “just ‘cross the border and into the city,” relying on “a little bit of money” saved up by working at a convenience store.

The narrator’s closest companion is a love interest, but he isn’t her only companion. There’s her father, too, whose body is decrepit from his alcoholism. When his wife got restless and left him, the narrator had to quit school to take care of him.

My circumstances could hardly have been more different when I fell in love my freshman year of college. Neither of us ever had a parent struggle with alcoholism. My father is a successful family law attorney and family court commissioner whose income allowed my mother to stay home with my sister and me. Her parents work for a college in the Chicago suburbs, her father as an economics professor and her mother heading the business office. (They graduated from Stanford and Harvard respectively, but – good Midwestern folk that they are – they’d rather not flaunt their Ivy League degrees.)

Since we were freshmen at a four-year residential college, it felt like undergrad stretched out forever before us, even as we would’ve acknowledged that of course we’d eventually graduate. In other words, we had enough remaining time in undergrad that we didn’t have to consider what a shared life might look like afterward. Further, we had enough idea of what degrees we’d pursue and enough academic time and space to not need to promptly nail down many specifics. We had enough family financial support that we didn’t have to worry about college funds possibly drying up too soon. Our material circumstances made it easy to fall into a cozy romance, and it was hard to imagine any change of material circumstance wrenching us out of our happiness.

I later wrote a poem about that relationship, and I want to draw from it now:

When dinner at the same old Commons

was enlivened by her smile,

when my same old suit felt regally handsome,

when The Faerie Queen – well, for an opera,

it didn’t put us to sleep - and

when my dance step was graceful for once,

in no light but the lamps that

shone on the water and the wooded river-walk

and snow-coated tree-branches

in through the pane-glass window-walls,

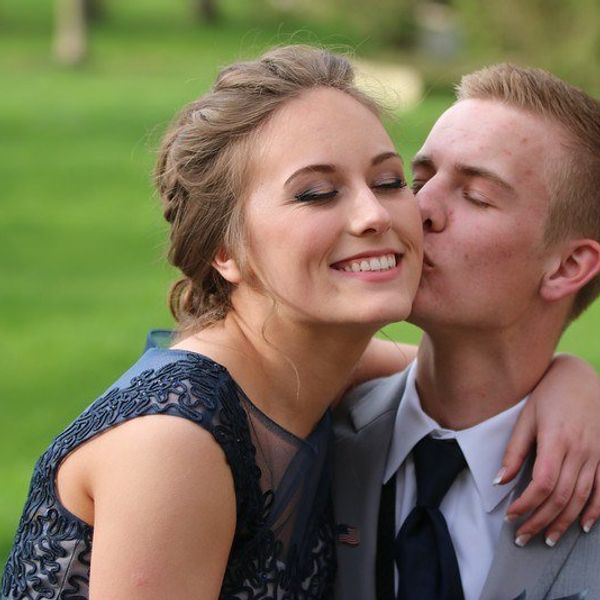

when at the last song’s end I kissed her

I remember thinking -

But later she and I broke it off.

The poem isn’t about affluence: I just wanted to kill the idea that a truly magical evening destines a couple for happily-ever-after. (Sorry, friends; Disney lied to you.) But that evening’s enchantment drew heavily from material factors: a nice dining hall, my good-if-not-new suit (and her gorgeous dress), a charming performance to attend together, and the opportunity to dance in a stunningly-beautiful venue. Our enchantment rose from nice things purchased largely by our relatively affluent parents. And, to draw on my earlier observation, that evening was able to feel like destiny because of all the enough-ness afforded by our particular type of college circumstance.

“Fast Car” made it easy for me to recognize how materially-reliant our enchantment actually was, and how fragile it would’ve been if we weren’t both so well-off. Suppose that my father was an alcoholic and that my mother leaving would mean me dropping out to care for him. Or suppose that her tuition relied on her father’s blue-collar salary, and that him getting put out of work would mean her leaving for community college back home. We could still have fallen in love, but only with the sense that our relationship could at least be forcibly stretched to long-distance by developments beyond our control. Our romance would have felt very different if not for the enough-ness afforded by our well-off families: in other words, our experience of romance was shaped by our class standing. Without certain forms of enough-ness, perhaps we would’ve simply ruled out a romantic relationship altogether. For example, we likely wouldn’t have started dating halfway through our senior year if we knew that our post-undergrad lives would take us to very different places.

That example illustrates a basic human tendency: the less likely you are to succeed at something, the less interested you’ll generally be in trying for it. Put together the range of satisfactions that you can probably grasp with the range of those that you probably can’t, and you have what might be called the incentive-structure for your particular circumstances. I think I would’ve always agreed with that in the abstract, but “Fast Car” deepened my thinking about how far certain circumstances and incentive-structures might really be from others.

A blog post by the journalist Rod Dreher, along with many of the comments on it, helpfully reflects my thinking about how this all relates to class. Several readers point out how poor people’s circumstances tend to put short-term and long-term interests in conflict for one’s immediate resources. Keeping perfect attendance for your minimum-wage job improves your odds at promotion and better pay, but it also means flaking on your pal whose car broke down or your sister who needs you to babysit because she’s sick. Compared to wealthier social circles, refusing a small favor can seem less like a slight inconvenience than a middle finger; a reason that’s important to your aspirations – “I can’t come because I have to finish this college application today” – can seem snooty and sow bitterness. Altogether, the immediate reliability of pleasures like human companionship holds much more appeal than unlikely long-term affluence, especially since – as Matt Bruenig has noted – a reasonable fear of ending up destitute deters already-poor people from taking chances in their business lives.

Mental habits that develop within particular circumstances may not disappear even if those circumstances change. For example, we wouldn’t be surprised if military kids who move frequently while growing up have difficulty forming deep friendships outside of family, even well into adulthood. Nor should we be surprised if many people imaginatively formed by poverty find it hard to shake a mentality of persistently choosing companionship and other immediate pleasures over thrift and diligence, even if real economic opportunity becomes available.

Of course, these tendencies are not universal. “Fast Car” itself tells of the couple reaching relative bourgeois stability, though they aren’t content there either. And real-life folk heroes like Ben Carson demonstrate how talent and plucky determination can put one on the ascendant socioeconomically. But if we’re willing to recognize these cases as literally exceptional rather than a universal template, we need to think about and address poverty and economic opportunity in a way that accounts for incentive-structures and that offers truly plausible economic opportunity as widely as possible.