The dining room door swings open and Frankfort’s butler of many years Pierre, pushes in a vintage bar cart carrying champagne cubes, a silver palate of meats and cheeses, a corkscrew atop, and Veuve Clicquot. The cart beams beneath Frankfort’s chandeliers, up to where he stands welcoming his colleagues. He remains vigil, upright, and fronting the table while Pierre pours him a drink. He then chimes three rings for a toast and raises his glass.

“I have an announcement,” he says. “First, your glasses high, your attendance on such late a notice is an appreciative reminder to the urgency of the arts. I thank you all! My announcement is quite pressing, and I ask your thoughts or concerns. I’m going to...”

-Pierre taps Frankfort and whispers into his ear standing by as Frankfort holds his glass, ‘a guest is here sir.’ He nods forward to signal them in and a plump shadow emerges at the seams of the dining room entrance where a burly voice calls out

-“Mulligan! Mr. Mulligan,” right thereafter.

A gasp levies the table in abrupt shock, Mr. John Banks. Frankfort grabs his wooden oak pipe from his jacket’s breast pocket and instead, pinches a bit of hash from the other to dip inside. He looks at Pierre lighting his pipe with a match and whispers back waving out the flame, ‘It’s fine, I’m well-aware he might show, get him a seat at the end please.’

He shifts his attention. “Awe, Mr. Banks! It’s you, glad you can join us this evening. Shall we?” He nods the go ahead to Frankfort.

“I’ll diminish my feelings for the personal invite Mr. Frankfort, but assuredly,” he thrusts his hand forward; “I couldn’t miss this one for the world, word-of-mouth travels fast you know.”

His belly heaves in and out with a hearty laughter. He was called “Rich Fatso” and “Mr. Knocked-Knees” on occasion, being known to stroll the cobblestone streets as if the town’s tax collector. He’s born out of old money and far as anyone knew, everything was an investment in the eyes of a Banks. The family had a garish attitude of respite when uninformed on the day’s news around town and Frankfort was deliberate in his planning. Mr. Banks’ hands aligned with his jutting and overhung stomach, as his white gloves remained tucked below into his curvy, pocket seams. He’d stride with authority and pat his overweight with indignation toward the lesser. Wobbling in further with his mahogany-wooded cane, Pierre follows up on ushering him to a seat near the left end, sitting opposite Ms. Lisa Finnegan. His mustache furls over his lip the same as his waistline, and everyone knows this was and is, the opulence of Mr. Banks’ reputation. “He’s more needed than they know,” Frankfort thought, puffing twice and lingering at Pierre.

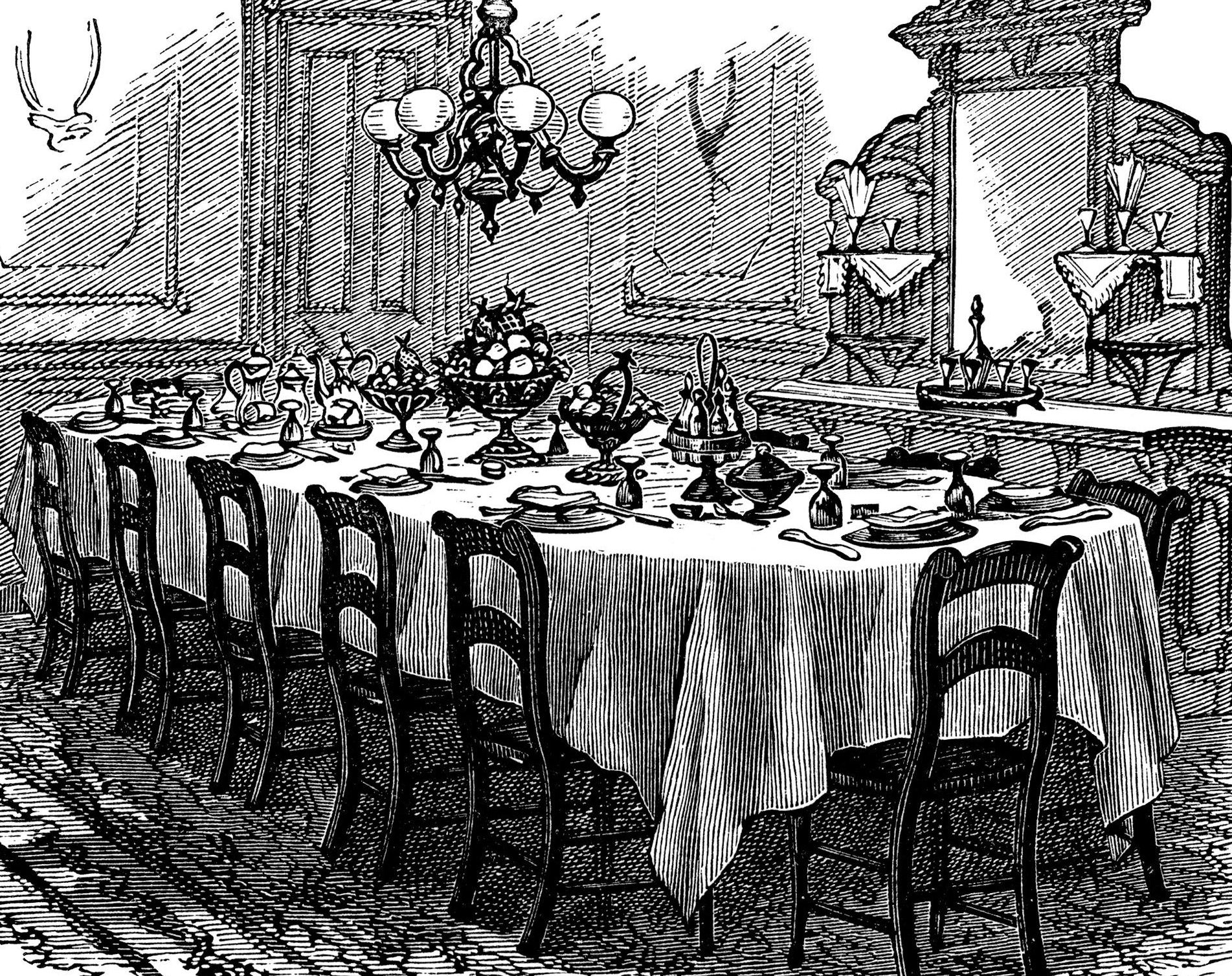

He looks over his glamorous table, spread vast in gold-trimmed plates and cutlery as each piece lay across white satin. The wine glasses beam beneath Frankfort’s chandeliers also, and while he watches his pipe’s midpoint spur another ember, all the faces there pulsate with surprising illumination. A gentle smoke rises from Frankfort’s overflowing pipe, and he straightens his eyes ahead to reconvene discourse. He grins a sly smile winking his eye at Mr. Banks.

“No problem John, all here are aware, or should be at least. Shall we proceed?” He nods again, sitting down in response to Frankfort resuming and sniggers a little.

Everyone dresses to par, knowing always and never forgetting that those present are scholars to no avail, and speech over troubling admissions is always Frankfort’s time of discourse. Though naïve it was for Mr. Mulligan, Frankfort sought his friends’ counsel even despite misconception being held.

“Your timing’s perfect!” Frankfort says, removing his pipe from the corner of his mouth. “Now what I have to say may shock some, but for others it’s been a long-winding road of contemplation.” Mr. Mulligan takes a breath. “I’m...retiring my craft.” Another gasp erupts the table into chaos, and everyone’s quiet murmurs become chattering noise, growing louder with voices of contempt crying out at Frankfort’s absurd speech, no longer attentive to Mr. Banks in mind.

“You can’t Frankfort, no!” Mr. Farley demands, pounding his fist in anger and rattling a few forks, knives, and spoons. “You’re quite disillusioned Mr. Mulligan,” Howard Schumer declares. “You bloody fool Frankfort you, after a near three years bringing me here for this!” Lady Glove shouts.

Everyone’s confusion turns quick, back into rumblings and quiet whispers amid the news. All are neutral as Lisa Finnegan decides to command her stance in shifting the crowd, making it her chance to reverse the objections.

“Wait a minute here, Frankfort may have a point!” Ms. Finnegan chimes in standing abrupt in middle the conversation. Raising both her hands to silence her fellow guests and then elevating one finger to point out Frankfort, “Only way we’ll know if it’s true, and really true...is by asking the most famous writer himself we know, our own prodigal son,” instilling minor sarcasm. “It seems to me, Frankfort asked himself too hard a burgeoning question, why. Why had it have to be dear old Frankfort at controversy’s front, robbing himself of what heprovides? Is it because he’d taken his own route out of disparaged feelings binding himself to a purpose, for which he’s never been responsible? Or is it just an inconceivable notion without any weight of truth?”

Frankfort keeps his face conservative throughout Lisa’s pandering, and he’d writhe a look toward her, raising his brow. He thinks to interject yet knows of her entitlement from brooding shame upon man’s patriarchy. He grabs his pipe, takes a puff, and reassures his guests. “Lisa, thank you. We both know the complication(s). I’m youthful still in my day and for many of you who’ve been reliable voices and a counselor of sorts to my upbringing, it’d seem hard to understand given our gaps when I departed. I only ask in truth, and for it. Is there not another in this room whose pondered retirement for sake of their craft’s authenticity?” He puffs again after his question. The chatter subsides a moment and Ms. Finnegan sits, leveling the crowd’s intemperance. And a voice says…

“I have, Mr. Frankfort. I’ve pondered retirement.” A person speaks up. “Awe, Mr. Farley. It seems you were the first response. Go ahead and kick things off old lad!” Frankfort cheers up his glass to take a seat and Pierre finishes up serving the crowd. A loud screech is then heard from Chad Farley pushing back his chair to stand after Frankfort sits. “My first admission is to ask what and when is it proper to say the right thing? I ask such a question, and in truth for such an answer.” Mr. Farley straightens up his back, thinning out his long shawl. “I used to say a prayer to Frankfort’s father during his tour in Germany after the war broke out and I’d question the meaning of retirement then as a cliché notion. I’d reminisce the postcards he’d sent, sculptures of Lehmbruck’s The Seated Youth and The Fallen Man, as he was documenting the carnage. The proper thing to tell him was to reprieve himself of the hysteria and come home, though I knew the causes for which he’d be there, and one of which was for you Mr. Mulligan. Now, talks of nationalism are beginning to spur themselves across all of Europe.” He pintails his gaze over the room. “I’ve known Frankfort much of his life and as a literary guidepost in his youth, I’m intrigued by his interest in the word still. I shared insight early on of our own residential halfway believers because I knew Frankfort had a gift. A gift that outweighed being chided by the schoolchildren for so many years, as his father in our time. So I’m thankful to the few of you who didn’t let him slip through the cracks and become stuck behind the ambition. As a friend to Father Mulligan and advocate, I pledged it wouldn’t happen, and here we are.”

Mr. Farley wears debilitation across his face and in his dress, opposing a normal appearance to match his heretical speech. He’d seem a starving huntsman isolated and alone, as if surrounded by rampant wolves most the time. His originality accentuates what he feels that morning, or day – if hung over the night previous and he was only there because of the cowardice of others he knew, beckoning a similar closeness to Frankfort that resembles a certain loyalty to the word inside him. And that is what he taught Frankfort as a boy in his father’s absence. A continuance on.

“The townspeople talk Mr. Frankfort and I believe you know. So, is it the people or the self you’re contending for a compromise of the word? Is this town part of your conviction? I pose my question to a few other brave souls.” He sits back gripping his chair and pushes himself under the white satin tablecloth, hiding his long shawl and sandals. Lisa stares Frankfort down for an answer and she turns her glass a smidge to call Frankfort’s bluff. In his mind he knew that saying anything would cause a stir, and especially from Lisa. He stares also and breaks after just a few seconds to snap his finger at Pierre, distracting from any reaction to occur, if at all. Pierre comes out the door from which he’d serve the patrons, standing in place for Mr. Mulligan’s next bid.

“You make the messiness of this life more fun to live with Mr. Mulligan, you know that?” Ms. JoAnn Copperfield exclaims. “And I believe God carved a path for you writers because you’re also still judged for murder, if it’s decided you become storytellers.” He sparks a grin to JoAnn, or Ms. Jo, as many called her and remembered the time in a glimpse where they’d met at a dinner party akin to his own. She’s a painter from North Evanston who’d catch Frankfort’s eye after conversation ensued on aesthetics in the arts world, where few of her paintings were being prepared for an exhibit. She’d been arriving from Belgium before tensions arose, and there he became hooked.

“Well, you share a grave point Mr. Farley,” as many at the table begin searching an answer.

“Then the question is for Mr. Mulligan, whose compromising for who?” JoAnn asks.

Frankfort wasn’t called Mr. Mulligan until his first celebration of endeavors where Ms. Copperfield was present. He’d been conversing with other prescribed intellectuals that night before leaving Evanston and some of those who knew of his rich beginnings, celebrated with discussion on the state-of-affairs embroiling the arts world as it was before everything changed. At his wit’s end Frankfort begun searching for Providence then himself, and there Mr. Farley’s younger brother – Dennis Farley, responds. “I’d often ask myself too if this work is perhaps timeless, he appeals to Frankfort. Early on in my knowledge of our beginnings, we’d drink every night as if we were fish breathing in water.” He cranes over the table leaning and Frankfort signals to Pierre for a fresh round of Cliquot, intrigued with Dennis’ acclimation. “At that point we drank heavily, scouring bars around town for the women arguing against man’s betrayal and fidelity. And as a man I learned most of my lessons that night, that a man will never steal anything before experiencing rejection.” Pierre walks over and refills the commonwealth at the table, after everyone’s first drink.

“I believe our dear Frankfort ceded away from home for those only he can trust in. At that point, how can you trust anyone?” Frankfort gives a gentle interrupting clap in middle of receiving his pour, - “It was hard escaping the flickering streetlights then Mr. Dennis, in your passing by, as we trawled through those long winding roads we remember. They were soddening bright shadows I’ll never take for granted, as I saw my face in them, below.” He drags his head in an acceptance of trial and error from the words he’d espouse. “It’s more the sense of being if I may. On one of those nights a man told me to look up and I’d be able to see everything. To keep my mind to the ground and my heart set above. And my word to the wind and one foot fronting the other. ‘You’ll get far, he said. Believe me.’” He takes a sip and peers at Lisa a moment but doesn’t break. She grins.

“Are you finished Frankfort, I’m continuing.” He nods. “See, I told Frankfort of that same dream I saw in hindsight when he rushed back to echo this. You remember? The night before of my dream, where Father Mulligan discussed establishing Evanston’s first Library. I remember travailing the streets late one night and talking with Frankfort. We’d been discussing Father Mulligan and his return, wondering what great mysteries might come out of the war. And then all a sudden, the cobblestone streets broke apart splitting in two, and cracks formed below our feet. The dark sky began crooning with swirls of gray wind and clouds. Officers from round all Evanston poured into every street corner with batons and bayonets, petrol bombs, and shields. When a bomb struck, my vision blanked. I’d only hear blaring screams from families being raided as books and assets were poached from their homes. A wrath of deceit mangled my ear drums. So, I lay there, praying and wondering if this were the early aughts of another war. I then felt my hands burning and when my vision reappeared, I was holding a fiery skull that began etching the words ‘this is it, storytelling is the final authentic mark succeeding any upheaval.’ It is why now I adore your chandeliers Frankfort, they’re a reminder in my eyes and your father gave me a chance to believe again, as did yourself. And unlike my brother whom everyone knows, my clarity and outlook were saved. I understood sacrificing praise to others and that when rewards run dry and the speeches end, yourself is who you got when asking who to save.” Thereafter when Frankfort left, Dennis wrote a book on the word ire itself, to ensure that writing’s aesthetic remained permanent in telling the story of Evanston. So as it goes, endorsing Frankfort’s claims in full contentment was out the question because he did not judge his gratitude, nor the timeclock for his departure. As any person would when encountering their own word he thought, in some cases the only challenge is the answer.

Frankfort peeks back in burning to discuss his issue. He knows Dennis is a piteous thief and sees Lady Glove swelling her lips for a word to add.

“Bollocks,” he’d say, that if Mr. Mulligan did not suffer doing it now, he’d remain suffering doing it later, but with regrets. And it’s that thought always buzzing in back Frankfort’s mind since the library’s conception that he now rises for another toast. “Salutations to Father Mulligan!” he says, “to Father Mulligan!” all shout, and they take their drink.

Birth anew! he cries

To whatever few choose

As the road lonely remains cold.

Companionship and alliance, our saviors of the soul.

Again strong, my steps better with age;

Confidence in age is how families grow.

For the belief I know, believing is wherever I go.

A wandering Mr. Frankfort, in where he knows!

Believe Mr. Mulligan! Because

The boy too, who rages

Only rushes, to grow old.

Frankfort’s work became the exaltation of grace covering the town’s bells rather than broken memories of existence. And though literature was demanding a renaissance in East Evanston as Mr. Mulligan had noted, an agreement begins to emerge.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion