High Renaissance art is known for its improvement of and mastery over the revolutionary techniques passed down by previous artists. Perhaps the most humble, talented painter to contribute to these improvements was in the 1500s, a man named Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Born and trained in Netherland, Bruegel was inspired by Hieronymus Bosch in the organization of his compositions: often showing many different interactions, covering the entirety of the pictorial space with detailed, independent, magic-realist figures. As his life progressed, Bruegel moved from a focus on religious/mythological works (Landscape w/Fall of Icarus, for example), to a focus on the everyday. The later, most cherished paintings of Bruegel depict peasants in chaotic scenes of celebration: he painted peasants working hard in the fields, hunting, celebrating, praying, mourning, etc. (Orenstein, whole book). Perhaps the most famous peasant painting Breugal created is titled The Peasant Wedding, 1567: created at the height of the Netherlandish Renaissance. During a time when religious figures dominated the subject matter in art, Bruegel decided to focus his brush on the less fortunate. During the reformation of the church, times of famine and poverty for the lower classes, and the threats of violence and disease, he felt the need to underline “The common, universal need for occasional indulgences,” (Lowe, DVD). This is the big, underlying theme behind The Peasant Wedding: the poor worked very hard and still had difficult lives, yet the indulgence of a wedding celebration seems to melt all of their concerns away. His thought process behind this was along the lines of logical reasoning: one cannot draw particular conclusions from universal premises; to do so is called the existential fallacy. The universal is the “divine” stream that runs beneath all things, for Bruegel; whereas the particular are instances of the universal in action. This is a major facet of all Enlightenment thinking, and it penetrates every piece of art at the time, especially Bruegel, who painted the particular (human) in an effort to get a glimpse at the universal (divine). In contrast with the divine art of the time, the content portrayed in The Peasant Wedding by Pieter Bruegel is singular because it acted as a catalyst for nearly all genre scenes depicting everyday life that would come in later years, across all media.

Figure 1, Pieter Bruegel, The Peasant Wedding c. 1568; Oil on wood, 45 x 64 1/2 in; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The Peasant Wedding by Pieter Bruegel depicts a group of people, all doing different activities, in a room with a table in the center (See Fig. 1). In the foreground to the right, there are two men carrying small round pastries, which they hold between them. In the foreground to the left, there is a young boy who has in his left (our right) hand what appears to be a plate, and his right (our left) hand is sticking his finger into his mouth. The boy is small, and sits on the ground; on top of his lap is a piece of bread. To the left of the boy, a man gaily pours liquid from a large container into a glass. Behind him, there are men playing instruments for a table full of people. The long table holds many figures eating, interacting with one another, and enjoying the music. At the very left of the composition, there is a door with people crowding in from outside; perhaps coming in to join the party. The scene as a whole presents many different everyday scenarios; from a man grabbing pastries to hand out, to people chatting privately between themselves. The varying and culturally accurate interactions between these peasants show their occasional indulgence during times of hardship, and stand as a very realistic representation of the culture of the time.

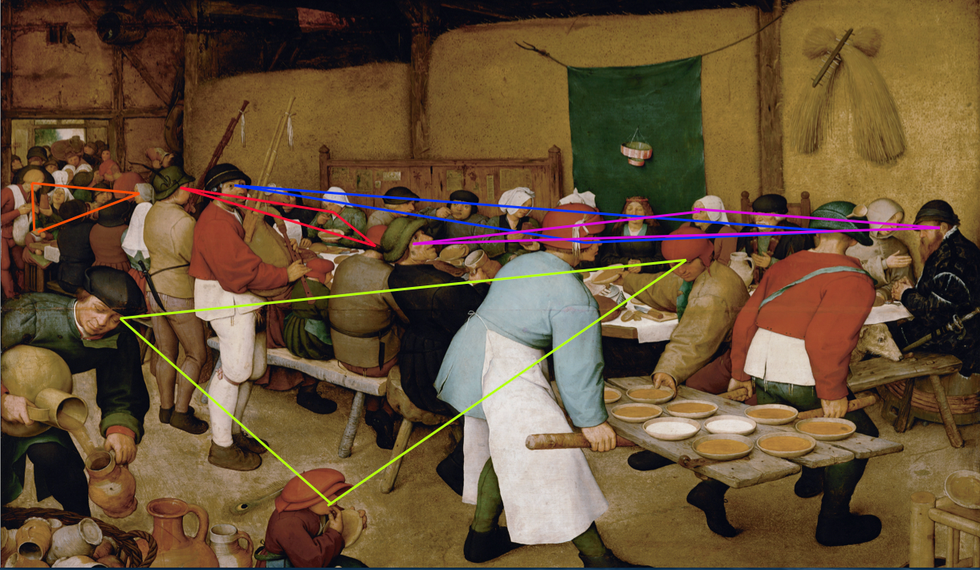

Unfortunately, very little is known about Bruegel’s life, aside from what we can conclude from the works that he created. Looking through the book The Drawings and Prints of Bruegel, it is clear that organization and symbology has been very key throughout all of the art he created, and that includes The Peasant Wedding (Orenstein, whole book). The Peasant Wedding’s composition is exquisitely balanced, and the space is realistically shown. Using figures receding towards the door in the back left of the scene as a reference for the space, Bruegel slowly adds in shapes using the gazes of each person; there are several instances in which the direction of the gaze of three people follow one another and create triangles throughout the composition; this placement of geometric shapes through gestures was no accident, and serves as an example of the unity and harmony that Bruegel tries to achieve between the subject and environment (See Fig. 2). This strict organization is then followed by adding meaning, or in this case significance, to each person’s gesture. The boy in the front left corner of the frame has his finger in his mouth, a plate in his other hand, and bread on his lap; this is suggestive of limited indulgence. Licking his fingers, the boy seems to be enjoying every last morsel of what he is given.

Figure 2, Pieter Bruegel, The Peasant Wedding c. 1568; Oil on wood, 45 x 64 1/2 in; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

By including many people enjoying food and ceremony, and making those people hard working peasants, Bruegel creates harmony between toiling and indulgence; perhaps that is why amidst the partying, the most noticeable figures are hard at work passing out cakes for everyone. Even though most people in the composition are eating, laughing, or having fun, the first figures to catch the eye are the two peasant men handing out pastries. Bruegel was sure to include this to show that there really are no people lower than the peasants: even at their own events, they must be the ones to serve themselves, they must still work hard even when relaxing. But still, the partying continues in other places throughout the composition; the man in the left of the picture pours himself what is most likely alcohol, and seems very happy in doing so. Many figures eat pastries, laugh and drink; the attitude of the peasants is apparent, knowing that they have worked hard, they can now enjoy good food and even if just for a second, be drunk and merry. Bruegel has captured very accurately through his observations the lighter side of peasant life.

The Netherlands in the latter half of the 16th century was filled to the brim with talented artists, many of whom were inspired by the work of Pieter Bruegel. The tradition of the time during Bruegel’s life was that of religious themes, mainly improving upon techniques of artists both of the time and from antiquity. Bruegel was inspired strongly by Bosch, who was in high demand at the time (Met Museum, Web). Bosch’s compositions focused on the follies of man, virtues and vices, and other religious themes using very intense, crowded, high-brow symbology. Bruegel, instead of depicting these same themes through the use of elaborate, confusing allegories, created “Genre paintings in a common vernacular.” (Lowe, DVD). Therefore, the main difference between Bruegel and Bosch becomes that Bosch’s paintings commit the existential fallacy: he is using divine laws in order to create particular premises (think of the hell panel). Bruegel, on the other hand, decided to explore what we may learn about the universal/divine when we closely study the particular. In addition, instead of instigating the separation of the lower and upper class, as most art seemed to do at the time (by creating overly-cerebral pieces) he combined elements of familiarity and common life, and knit it together with landscape and interaction, all in a style that pleased intellectuals, kings, and peasants alike.

The depiction of a simple, secular scene in The Peasant Wedding made art more accessible for the lower class, as well as expanded the subject matter available to artists at the time. Genre painting exploded in the Netherlands after the works of Pieter Bruegel, becoming an almost exclusively Flemish tradition until the 1700s. “Flemish genre painting is strongly tied to the traditions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and was a style that continued directly into the 17th century through copies and new compositions made by his sons Pieter Bruegel the Younger and Jan Bruegel the Elder,” (Drawings and Prints, whole book). The transition of a style originally specific to Bruegel, into a style that became traditional throughout Flemish art is an amazing accomplishment for the artist; the beauty and truth of his paintings inspired the creation of these truths by many other artists. In the 1700s, genre painting made its way throughout Europe, beginning in the Dutch Golden age, moving to Spain during the Spanish Golden age, leaking into the Realism movement in the 1800s, hovering throughout Impressionism, and making a hearty return in Modernism and Postmodernism. The idea of normal everyday cycles of life, using figures who are not immediately identifiable (i.e no Angels, saints, etc.) became the way that artists around the globe decided to render their world. Instead of focusing on the ease and pleasures of wealth, or the tradition/ritual of religion, Bruegel and artists that followed depicted what real life was: most people were not rich, care-free, and certainly no one was an angel, saint, religious figure etc. Most people split their time between work and home: environmental portraiture, genre paintings, and the modern Realism movement are all present day examples of this idea of a human type of truth. Without the contributions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, later artists may not have focused their attention on the unacknowledged aspects of the world. Considering that genre scenes, worker’s lives, and less appreciated things in life have become the subject matter of a lot of modern art, and famous works of art from the 1700s onward — and considering it is this subject matter in art, and this subject matter alone, that has fueled revolution/protest rhetoric — it is hard to say how far behind the world of art would be if it were not for the advancements Pieter Bruegel shared with the world.

Works Cited

- Wisse, Jacob. "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History." Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525�1569). The MET, n.d. Web. 04 Feb. 2015. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/brue/hd_brue.htm>.

- Crenshaw, Paul, Rebecca Tucker, and Alexandra Bonfante-Warren. Discovering the Great Masters: The Art Lover's Guide to Understanding Symbols in Paintings. New York, NY: Universe, 2009. Print.

- Bruegel, Pieter, and Nadine Orenstein. Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001. Print.

- Bruegel. Dir. Lara Lowe. Perf. Biography. West Long Branch, 2006. DVD.