President-elect Donald Trump will face a world in transition when he is inaugurated in January. There are a series of issues in every geopolitical theater across the world that the U.S. has strategic interests in. From the hell that is Syria and the battle for Mosul in Iraq; from the foundational crises that Europe faces to the geopolitical chess game in the East Asian seas, the United States faces issues that will affect the world for decades. As the future President, Donald Trump will be at the helm of many of these decisions. Over the next few articles, I will attempt to illuminate these issues and explain their significance and what interests the U.S. has. Last week, we talked about East Asia. This week, we travel to Europe.

Europe faces deep-seated problems that threaten the stability it has established since World War II. To be specific, the European Union faces crises that threaten its very foundation. The EU was founded in 1993 and preceded by the European Economic Community. It is the world’s largest free trade, single market economy, in which goods, services, and citizens can travel freely across borders without barriers. There are 28 countries in the EU (still including Britain) with over 500 million people. The total GDP of the EU is over $16 trillion, placing it within spitting distance from the U.S. The EU is also a nexus of international relations, playing host to the International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice, and the various Nobel Committees that nominate people for fancy prizes.

By order of the Schengen Agreement of 1985, European citizens do not require a passport to travel across countries that are party to the agreement. Migrants can move relatively easily in the EU and financial markets are integrated so that capital can move seamlessly across the member states. The Euro currency is specifically used within the Eurozone, which encompasses 19 of the 28 EU nations. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) designated the Euro as a reserve currency, meaning that it is one of the most used currencies in the world. There is also a European Central Bank (ECB) that administers monetary policy for the Eurozone. The ECB takes care of things like interest rates, quantitative easing, and maintenance of foreign exchange reserves of the central banks of individual Eurozone countries. Broadly speaking, the ECB tries to maintain price stability within the Eurozone. Yet every individual Eurozone country has its own central banking system that establishes fiscal policy, which encompasses how a government taxes and spends money. This is where shit starts hitting the fan.

Member states of the EU

A democratic government normally negotiates among its political parties to work out fiscal policy. The United States’ infamous stopgap measures are an example of this: when Congress is divided and Democrats and Republicans can’t decide how to fund the government for a full fiscal year, stopgap bills push the can down the road by funding the government on a short-term basis. This theoretically gives Congress more time to work out a proper deal, but they usually just procrastinate like how I did in writing this article. Nevertheless, politicians work out fiscal policy in a democratic government. Monetary policy, on the other hand, is usually formulated by central banks. The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the U.S. and its officials are nominated for 14-year terms. They do not answer to an electorate, are not funded by Congress, and do not need approval from the President to pass its decisions (although the President can nominate the Fed Chairperson, who is currently Janet Yellen). This gives the United States central bank great autonomy. The ECB is structured differently, but it also does not answer to any single government in the Eurozone. Yet the ECB sets monetary policy for a group of countries that all have different fiscal policies. Over the past few years, this has proven to be a glaring oversight and a cause of economic mayhem.

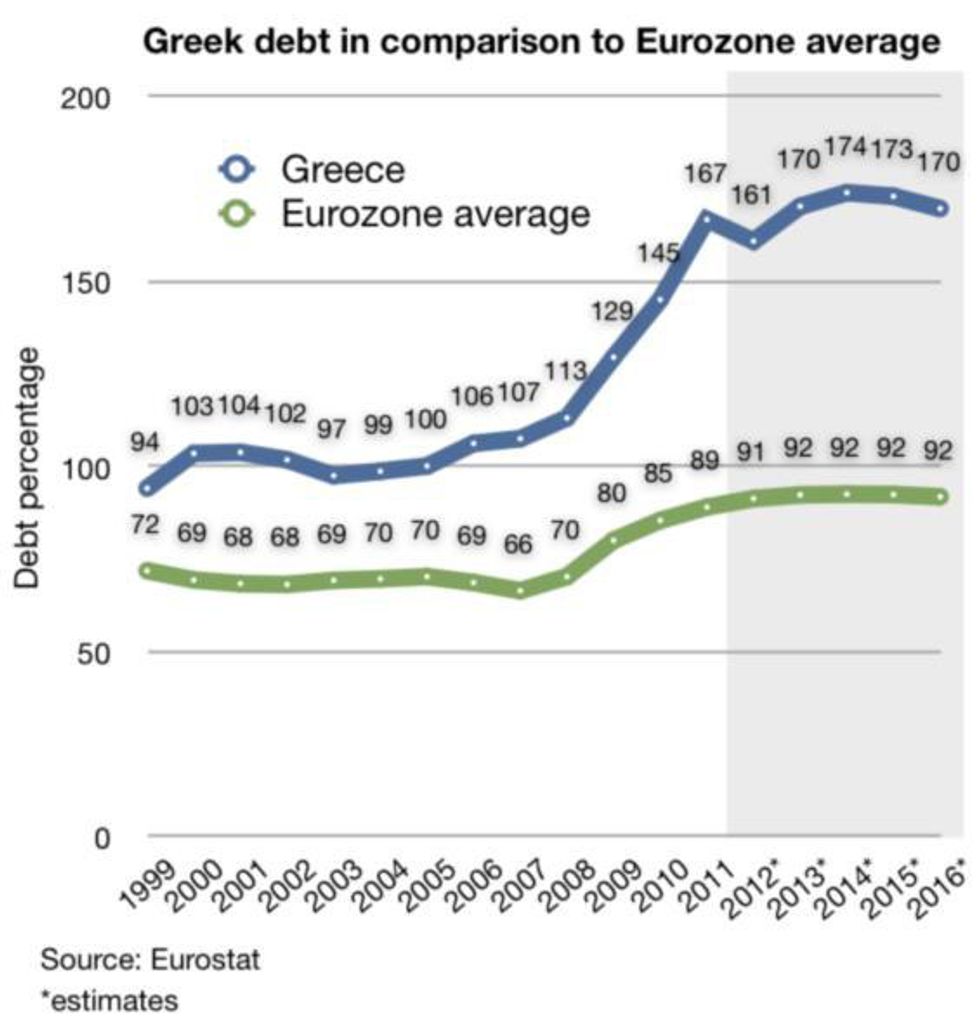

Before Brexit happened in July, many people were worried that Greek would leave the EU. Grexit, coined by a Citigroup economist, was floated as a potential solution to Greece’s government debt crisis. Greece currently has a national debt-to-GDP ratio of 175 percent, which is kind of like saying the government of Greece owes more money that its economy is worth. It is typically seen as bad for a country to have its debt-to-GDP ratio above 100 percent. Since debt rises for a variety of reasons, steady economic growth is vital to keeping this proportion below 100 percent. Greece’s national debt is so high partly because of high public sector wages, an early retirement age, and overly generous pensions for public sector employees. These factors, combined with a high unemployment rate, created the circumstances for borrowing more money to pay for Greece’s financial obligations.

Greece became the center of the European financial crisis after the global recession of 2008. In 2010, the ECB, the IMF, and the European Commission, referred to as the troika, issued two rounds of bailouts worth €240 billion. The conditions, however, were a series of tax raises and budget cuts meant to decrease public spending. This became known as austerity. Several European countries have enacted austerity themselves in order to deal with their own budgetary constraints in the face of low economic growth. While many economists debate the effectiveness of austerity, most agree that only sustained economic growth can pull Greece out of its debt crisis in the long run. Moreover, austerity proved to be deeply unpopular among the Greek electorate. After a series of protests and riots, Greece installed the Syriza Party as its majority party and Alexis Tsipras as its Prime Minister. PM Tsipras swept into power on the promise that he would negotiate with international lenders to do away with austerity.

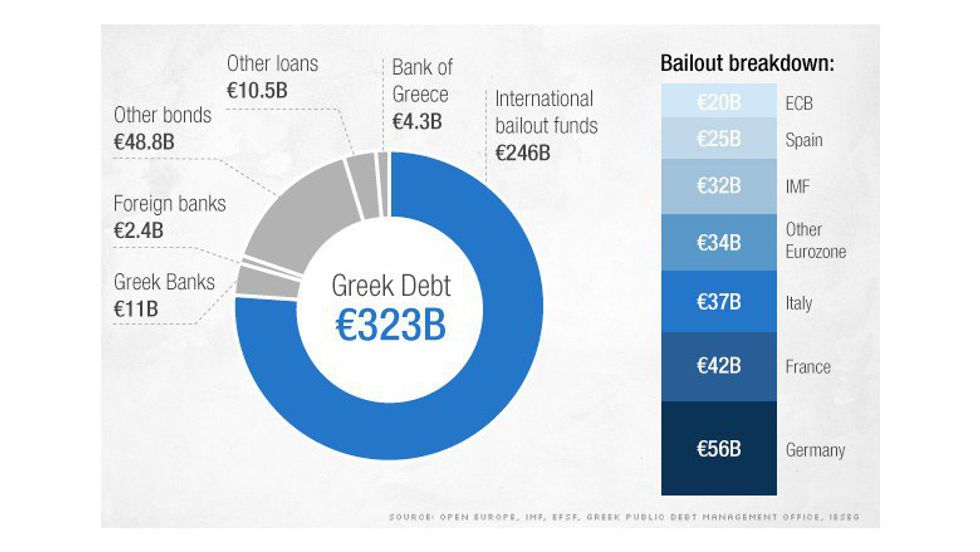

These lenders include the troika that granted the original bailout deal. It also includes Germany. Here, we can see why leaving fiscal policy to individual governments and monetary policy to the ECB is a glaring oversight. Greece became a crisis spot on its own failings. Its government was responsible for maintaining its balance sheets and it failed spectacularly. This may not have been such a huge problem if economic growth was consistent, but it wasn’t. The ECB in turn granted money as part of a bailout deal. Yet that money comes from the member states of the ECB, of which Germany is the most economically successful. This in turn forces Germany and its taxpayers to pay at least part of the Greek bailout. They are in essence paying for Greece’s screw-up. Never mind that Germany has been fiscally responsible and has achieved steady economic growth throughout the global financial crisis. They must now pay for at least part of another country’s mess because they are joined together in the Eurozone. This is why Germany and the wider troika were able to force Germany’s hand to submit to austerity.

This tells us where the bailout money came from- Germany clearly paid the most for Greece’s mess

All of this has lead to the idea of Grexit- or Greece leaving the EU, and by definition the Eurozone. Much of the bailout money Greece received from the international community found its way right back out of the country as interest payments. So long as Greece owes money to multilateral parties, little of the income earned by Greeks themselves will stay within their own economy. Rather, Greece could exit the Eurozone and revert to its old currency, the drachma. However, the drachma would surely be worth less than the Euro. This will have disastrous short-term consequences: the net worth of the average Greek would decrease, as the Euros would be converted to lower value drachmas; and the price of exports would increase, as Greece would be trading drachmas for goods originally priced in higher value currencies. The exports industry would do very well, since Greek businesses would be earning in higher value currencies, but the Greece imports more than it exports. The reversion to the drachma would be a net loss. Some economists, however, argue that this would relieve Greece of its austerity measures. This could allow the Greek government to finally focus on spending within its own economy and hopefully jumpstart economic growth.

If Grexit were to leave the EU, it could be very good for Greece. But it would also cause a crisis for the Eurozone, and potentially for the wider EU. It would also be an affirmation that the Eurozone had a terribly flawed setup from the beginning that it cannot overcome.