Pedagogies of Place Course Description: An introduction to environmental philosophy. Explores the formation of our relationship with the natural world and the roles of education and schooling. Concepts of nature, wilderness, ecology, and environmentalism considered and critiqued in light of their functioning as "normative ideals" for a right relationship with the more than human world.

E: I spent the last sixish years honing my ‘wilderness’ skills and experiencing outdoor education. This made nature a romantic ideal, not easily found in the everyday dealings of life. Sublime was desirable and could not be found in the flat plains of Indiana. Great mountains have character. Sheer cliffs, vast forests, and blue waters create the ideal nature and ideal place.

Having lived in the Whitewater Valley of Indiana/Ohio for now over three years, I never thought about the place other than the microcosm of the Earlham campus. I was here to go to school, not to experience the midwestern culture and landscape. When nature is sublime and school is mundane, can the two interact? Will I learn how that’s possible in this class?

D: This sounds...interesting! Fall 2016, that’s when I will be back from about a month in Iceland. A month spent hiking glaciers and volcanoes and learning how to duck from arctic terns. The kind of terrain that pushes one to reflect on their relationship with the natural world.

But Richmond, Indiana? How does one form a relationship to flat, boring plains? To a place where Ranch dressing is ubiquitous, and pepper is considered spicy? What even are the “normative ideals” of nature, wilderness, ecology, and environmentalism here? How could forming this relationship be relevant to my education at Earlham?

The Whitewater Weekend: An Inspiration

Our first glimpse at experiential education intertwined with notions of place was the class’s Whitewater weekend. The focus of this trip was to understand where our water comes from, and how we are connected to this land through this water. We visited several waterways in Richmond including the reservoir. After exploring our town we moved south to Brookeville where we watched motor boats speed through the reservoir there, pulling tubers along with them and playing loud music. The dam in Brookville was built to create the reservoir right on top of what used to be the town of Fairfield. We then stopped at the East Fork River. We canoed several long kilometers down the winding river. Our last stop was a night at the Ferris Farm., where we spent the night camping. The river ran through their property and fields surrounded the rest.

D: Camping, Canoeing in Indiana. Waking up in a sleeping bag covered in dew.

This weekend was many firsts for me. It framed my views, expectations, and excitements for this class while teaching me how to appreciate Indiana. As we drove from the reservoir to Brookville to the Ferris Farm, I was actively engaged in thinking about how our easy 30 minute drives were possible because of roads that had forever changed the landscape of what used to be wild Indiana. As we waded our way back to the warmth of the Ferris home from an aqueduct that used to be a part of the canal system in Indiana, I pushed myself to think about the role of the structure we had just visited in shaping the Indiana I am now familiar with. When we gathered around the bonfire that night, thankful for a good meal and engaging company, we prodded each other to think about place: how the physical place we were occupying was shaped and the remnants of that shaping process was, quite literally, in our backyard.

This trip was over in roughly 24 hours. It started me on the path of seeing the landscape of Indiana in a completely different light. Suddenly, I knew about canals and disappeared towns, and where to look for tell-tale signs about their remnants. I was hooked. I wanted to go look for these signs and find the Indiana that had been just below the surface, waiting for me to be curious enough to scratch the surface.

This place responsive project, for me, was exactly that. It was a way for me to scratch the surface, peek under the blankets, and explore the exciting, unexpected and dynamic things I found just below the surface.

E: As we ate our lunch sitting by the dam in Brookville, I was acutely aware of a choice that was made there many years ago. A choice that obliterated the town of Fairfield to create a recreational lake. A choice that displaced hundreds of people from their only home. A choice that allowed a handful of college students to play loud music, drink warm beer and go tubing on Labor Day Weekend.

My awareness shifted as the day progressed into the afternoon when we went canoeing on the East Fork River. It shifted to be aware of the hundreds of people sharing the river with us. It instigated a knee-jerk irritation at the loud music, beer cans, and plastic wrappers being strewn across the river on this popular canoeing day. This was nature, it was supposed to be pristine and prompt reflection, not boisterous and crowded.

This same awareness, later in the day, caused me to question my knee-jerk irritation. Sure, they were being loud, and sure, it wasn’t what I had pictured. But they were engaging nature in their own way, and who was to say my way of engaging was better?

As the day wound down and we huddled by the fire at the Ferris farm, my awareness shifted again. It settled on the rooted history of the Ferris family, a history so different from my own, that it was almost foreign. Every generation of my own history had moved to a new state or country, whether that was Finland to Michigan to Illinois to Colorado or the Azores to Massachusetts to Rhode Island to Colorado. This family, who had just welcomed us onto their land, fed us, and shared their incredible history with us, had lived on the same farm for generations.

The awareness of these choices and histories came from the framework of this class. It allowed me to see the sublime in the mundane and the wild in the domestic. I came away wanting to learn more, and expand my awareness more broadly. To learn about other stories in the state of Indiana, which had just gone from being plain and flat to dynamic and filled with mystery.

This place responsive project was my way of learning these stories. It was my way of experiencing the culture and history of this state around me.

Part I: Metamora

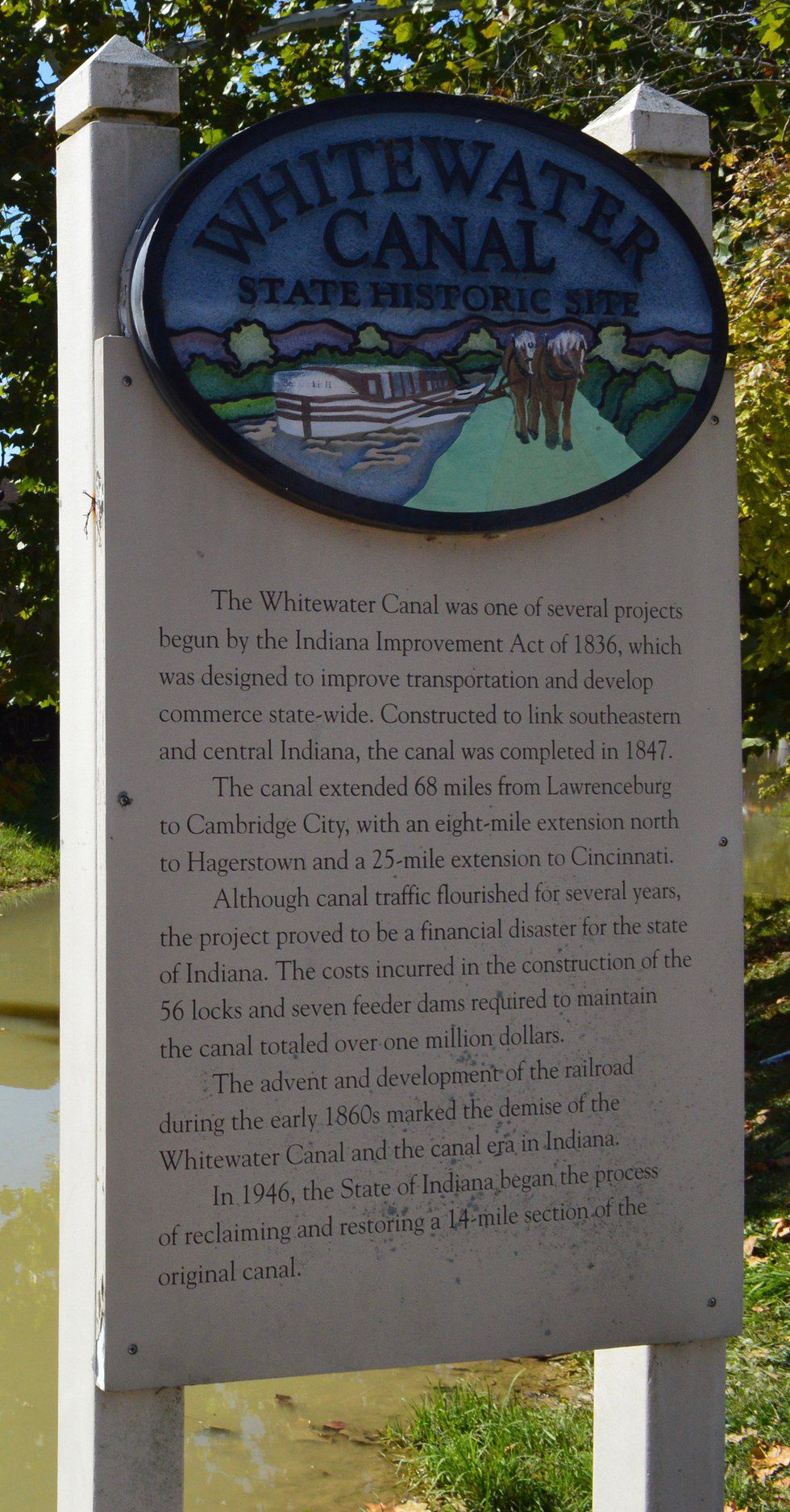

During the whitewater weekend, we visited remnants of old aqueducts that littered parts of Ferris Farm. The Whitewater Canal was constructed in the early 1840’s to provide an easier way to transport supplies between towns in the Whitewater Valley. A canal is a flat waterway shallow enough to allow a team of horses to pull boats between the towns.

Aqueducts were constructed when the construction team needed to get the canal across a waterway. They are simply bridges over rivers to allow another body of water across.

The Whitewater Canal ran straight through a town called Metamora and the aqueduct in Metamora still stands today, decades after the canal was abandoned. The canal today serves as a historical tourist attraction. One weekend in October every year, the town of Metamora hosts ‘Canal Days’, a festival that attracts many visitors from the surrounding counties and beyond. The small cobblestone streets fill with local vendors, food stations, and artists.

We were both very interested in the history of the

D: Grape juice sweetened fudge and almond bark, fruity scented tea stores and $1 trinket stores. These are my most vivid memories of the things I experienced for the first time at Metamora. I am not from a small town and had never been to a festival in a small town. Before we left, I fretted about appropriately layering, car logistics and sunscreen. I used mundane things to cover up my real hesitations: I was convinced that I would somehow be foreign in this town of rooted locals. I would be too brown, too urban, too naive or too withdrawn. I switched scarves, exchanging the Palestinian keffiyeh I was wearing for a plain black scarf. My mindless nitpicking reminded me of Rebecca Solnit’s reflections in her book Wanderlust, where she says ‘I was advised to stay indoors at night, to cover or cut my hair, to try to look like a man, to buy a car, to get a man to escort me.’ (Solnit, P. 241) My anxiety for my experience in small town Indiana was two-fold: we were an all female group that day, and I knew Metamora to be a racially homogenous town. As a brown woman, I did not know what to expect, so I stuck to expecting the familiar: hostility.

I discovered, surprisingly, that I seemed to be only one who cared about my racial difference at the festival. The weather was beautiful, and the people I interacted with were welcoming and warm. I was soon at ease in the bustling festival. I bought dairy-free fudge from a local shop-owner with kind eyes and a golden tooth. I learned I was younger than his typical clientele by about 20 years since most people who requested dairy free fudge were severely diabetic.

Unintentionally separated from my friends for a while, I sat silently at a little Amish store. I overheard to conversations about school assignments, truck hassles, and expensive jewellery. In my silent bubble, I hoped to catch glimpses of conversations about the canal or its history. Quickly dejected that people seemed to be discussing everything but the canal, I prepared to layer myself so I could find my friends. Surprised by my own response, my thought process shifted. It turned inward and questioned my dissatisfaction. I contemplated my expectations.

Questioning where I was coming from made me laugh. Here I was, drawn to a small town in Indiana purely because of a historical canal, at a festival celebrating this canal. It was bustling, the people were welcoming and the experience was lively. I realised that it didn’t matter that nobody seemed to be talking about the canal. Whether they flocked to the town that day because of the food, the music, the wares or the people, they were preserving the history I was so interested in hearing them articulate.

I smiled and spotted my friends. They were buying lemonade and preparing to leave. I opened up Snapchat to document our outing on the interwebs, and the stall-owner laughed at me. In the 15 seconds I’d spent trying to get a picture at a perfect angle, he had asked me if I wanted lemonade, and I’d responded with distraction. We left holding ‘Canal Days’ cups and applying Snapchat filters. We were responding to this place in our individual way while being grateful for the opportunity to participate in a local activity steeped in history.

E: Beyond the wall of trees was another world, bustling with activity. Booths filled with gourd and pumpkins greeted us, next came other agricultural produce and many bales of hay. I walked through the streets watching the people and photographing the history of this place. The canal and historical buildings were fascinating. I perused the antique shops, filled to the brim with relics of the past. Tiny colored perfume bottles, hundreds of old comics, streets signs, tattered books and much more. I walked through sweet shops and along the farmlands… if it wasn’t town it was a farm. Shop owners made small talk and the train conductor waves at us through the open window.

I noticed small things: Trump signs, snippets of conversation, confederate flags, little to no diversity. “Being country folk, having a “country” sensibility was as uncool in hip circles as it was in mainstream culture” (hooks, P. 172). I came into this place expecting a conservative, unaccepting experience and even though I picked up on the little things those people were walking through life just as we were. I did not have a single negative experience with anyone. I made assumptions about people because they are from the farmlands of the midwest.

Agriculture is a central part of life for many people in this area but that is not defining who they are as people. And just the same a negative outlook on people of a certain background does not take away the beauty of the place.

Part II: Wesler Orchards

Farming is such a huge part of the local Indiana economy, and neither of us is from farming families. After visiting the Ferris farm and learning about how unique a farmer's’ connection to land can be, we made it a priority to visit another local farm, The Wesler farm has existed since 1930. The farm added a kitchen along the way to sell homemade baked goods made with produce from the farm.

E: Rain threatened us throughout the drive. The winding road took us past dozens of farms. Aside from a few trucks and an Amish buggy, we did not see other drivers. Leaves of orange, brown, yellow and red guided our way up the driveway.

D: Driving up had one feeling festive. Their pumpkin collection was displayed right outside their homemade bakery. The entire experience made one ready for sweaters, soup, and thick socks. The store was still selling several varieties of homegrown apples, although only one of the varieties was still available for fresh picking. Since we were all excited to pick our own fruit, we got instructions on how to find the variety still available and were off. In about half an hour, our bags were overflowing. We were relatively late in the apple-picking season since we only visited in late October, but the trees were still abundant. A haunting image of this farm was a dead looking tree: From afar, this tree appeared to be diseased and dying. The closer one got to it however, it became apparent that it was still bearing fruit. When we got quite close to the tree, we saw that it was not only alive and thriving but the tree that bore the most fruit by far. The image was slightly eerie since every part of the tree appeared to be dead except the abundant ripe red apples it bore.

E: I walked through the rows of apple trees, searching for the few that had been left by previous pickers. It became exciting to find the ones that were not covered in bruises or worm holes. I imagined what it was like when the trees were ripe with fruit, waiting to be relieved of the heavy burden. I took a bite of one, it was delicious, sweet and fresh. Back in the farm store I drank fresh cider and watched their farm animals as they curiously stared back at me.

“In Wendell Berry’s important discussion of the relationship between agriculture and the human spiritual well-being, The Unsettling of America, he reminds us that working the land provides a location where folks can experience a sense of personal power and well-being” (hooks, P. 36).

Sources:

belonging by bell hooks

Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit