Recently, I've begun listening to the podcast series, My Favorite Murder. If there's anything to be taken away from this rather morbid, yet disturbingly charming and hilarious true crime podcast series, it is this: a surefire way to get murdered is to be a beautiful young woman, live somewhere on the West Coast in the '70s, and hitchhike.

Listening to this, though, begged the question of why exactly the prevalence of hitchhiking has diminished so greatly. Once a commonplace sight along backcountry roads, hitchhiking is now a taboo. It is the utterance of every mother to never pick up a hitchhiker and to never hitchhike yourself. But why is this? What brought about this complete reversal of practices? What precipitated the end of the road for hitchhiking?

Like most cultural shifts, the issue of hitchhiking is a multidimensional one. Economic, industrial, social and cultural issues all pervaded in erasing hitchhikers from the American landscape. Alan Pisarski, a transportation researcher, commented on what factors proved detrimental to the existence of hitchhiking.

"Simply put, the existence of the interstate system is a factor of major influence and importance. It took people out of the traditional road system and separated them from vehicles," said Pisarski. "Additionally, the ubiquity of the automobile can be to blame for the 'fall of hitchhiking.' It was originally assumed that each household would own a single car. Then, in the '60s and '70s, cars became far more readily accessible and available to far more people."

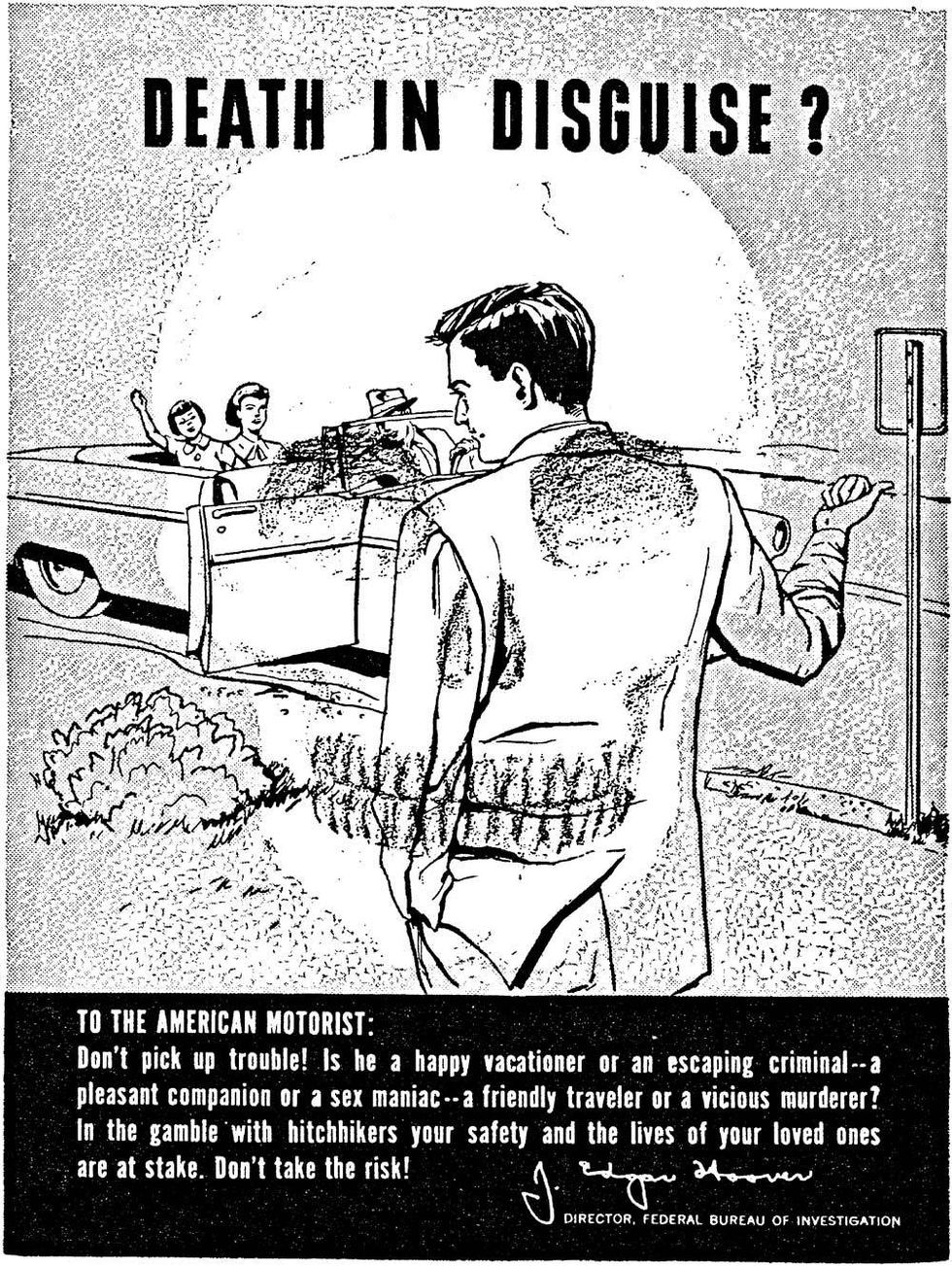

Over time, cars have become cheaper and lasted longer. It's also much harder to hitch a ride when cars are whizzing past you at 60 miles per hour on a four-lane highway as opposed to meandering through a small and friendly town. Additionally, some states, including New York, Nevada, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Utah and Wyoming, actually ban hitchhiking. There was also a villaInization of hitchhikers from law enforcement agencies, such as this FBI poster put out in 1973, which advertised hitchhikers as "Death In Disguise."

"Coming out of the war, there was a sense of cooperation, coming together, helping out your fellow man," said Pisarski. "There was a real shift in mental attitude, a shift from 'we're all in this together, we all have to help each other,' to a kind of fear and distrust of people. My children hitchhiked when they were younger, but have said they would never let their children hitchhike now."

The paranoia surrounding hitchhiking was compounded by the media; news outlets told the most horrifying stories because those were the ones that drew in viewers. Indeed, there are countless examples to support this frightening narrative: the brutal assault and attempted murder of Mary Vincent; the death of seven female hitchhikers in Santa Rosa; Colleen Stan, who was hitchhiking and kidnapped by a couple, then forced to be a sex slave for seven years; the list goes on and on.

"There was a real shift in mental attitude, a shift from 'we're all in this together, we all have to help each other,' to a kind of fear and distrust of people."

These crimes are gruesome and despicable; yet, despite the sensationalized media attention, the percentage of likelihood of being killed or raped while hitchhiking in the U.S. has been calculated and amounts to a whopping 0.0000089%. Compare this to the likelihood of being the victim of a violent crime simply by living in modern-day Chicago, which is calculated to be one in 90 (or 1.11%).

Perhaps hitchhiking isn't dead and dying as much as it is evolving. Ride-sharing applications such as Uber or Lyft allow you to get into the car of a total stranger, but the rating systems they offer provide a sort of vetting process and an assurance of safety. But the traditional form of hitchhiking, thumb up or cardboard sign in hand, has been relegated to the archives of history.

At the Smithsonian Museum, for example, there is an exhibit relating to American transportation and travel and one portion of the exhibit is entitled Pete's Postcards. Curated through the lived experiences of Pete Koltnow between 1948 and 1950, a series of postcards from cities along his 10,000 mile journey act as an homage to an era in which young people could stick out their thumb, a single bag in hand, and find rides across the country from coast to coast.

"It's so easy to idealize the past that it sometimes can mislead you and you tend to forget the bad things. Sometimes the opposite happens. And you just look back and you've survived it and perhaps realize that the threats were as real then as they are now. I guess my sense of it is that, now, we live in a more uncertain world and may be suffering from too much information. Maybe a little bit of ignorance may be a little more helpful, whatever the dangers may entail," said Pisarski. "I think that, now, people have a darker view of others, especially those different than themselves. But maybe, if they just stopped every once and a while, they'd be surprised at how little they have to fear."

Through these research endeavors, I've discovered for myself a great many things once lost. Under the façade of distrust and disdain, marked cynicism and unmarked graves that hitchhiking has acquired, I've trekked to a bygone era brimming with trust, empathy, helpfulness and a sense of blissful adventure: a time when there were travelers with wanderlust in their eyes for which no end of the road was in sight.