In the eighteenth century, flute performance repertoires were composed in a unique fashion uncommon to any prior time period. Great composers like Bach, Quantz, Vivaldi, and so many more existed during this time, producing great works of music. Comparable to modern day flute performance pieces, composers of the eighteenth century required criteria specifically for flute composition. Collectively considered, the eighteenth century can arguably be named one of the most influential musical times because it helped shape modern day flute performance.

In the 16th century the flute was very popular amongst Italian works and its popularity continued to grow and spread all through Europe. King Henry the VIII even developed an interest in the instrument, collecting various forms of it. The instrument was originally simple in form. It was composed of a cylindrical tube with a cork stopper on the top end, six vertical holes, and a single blowhole along its side. The flute was created in many different sizes to sustain a certain range. Unfortunately, by the mid-seventeenth century the flute became unfavorable due to it’s inability to keep up with the expressive repertoire that was being more commonly composed. The violin grew in popularity because of its human-like ability to "sing” the notes that effectively helped 16th century composers convey the emotions embedded in each composition. In response, flute makers took this as a challenge to make improvements on their instrument and create something entirely new.

French flautists and also flute makers who were appointed by the royal court, the Jean Hotteterre family, created a flute in the seventeenth century that was no longer one body but three pieces.

Figure 1 Baroque flute later modified from being one piece to three pieces. The Body (middle) is split into two pieces creating the corps de recharge.

While the headjoint of the flute stayed cylindrical, the body became cone-shaped, with the footjoint being smaller than the rest of the instrument in diameter. The footjoint also stayed cone-shaped while the bore became bigger at the bottom end of the instrument. The instrument remained with six holes, but with an addition of the E-flat key. This instrument now had the ability to play all of the notes to the chromatic scale. By the 1720s, the flute was divided into two parts and additional joints all of different lengths called the corps de recharge. This allowed the instrument to shift the pitch to match whatever orchestra the performer was performing with at that moment. Regrettably, due to the cross fingerings the instrument sounded its best in the concert keys of D and G Major. There were still amateur players who performed, though out of tune, but advanced performers of the instrument mastered the ability to change the pitch when necessary. Once understanding the abilities of the flute pertaining to its pitch tendencies became more widespread, stylistic creativity of the baroque genre began.

The baroque flute gave a sound that was like no other. It had the ability to give almost a “covered” sound. In the lower register, especially d1 to a1, where soft compared to the notes that was about g2. When performing stepwise notes, some notes were loud and clear while others seemed to have been muted. The baroque style can be studied from Andre Campra’s opera-ballet, L’Europe galante (1697), and the instrumentation was often written out with several instruments on one staff. The flutes, along with other woodwinds, often doubled with the upper and lower strings. By doing so the overall balance of the instruments creates a single blended tone color, but this also brings issues for woodwind instruments to make the sound continuous.

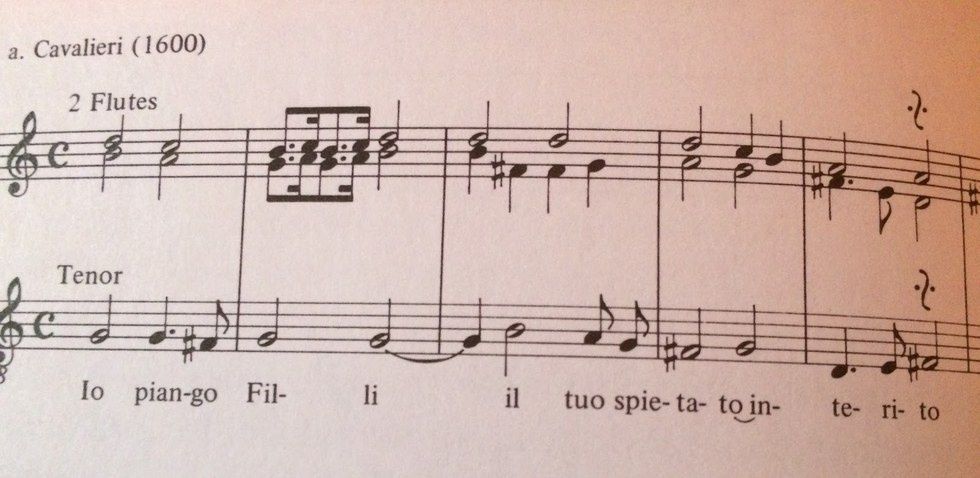

Singers, woodwind players, and brass players must breathe. It is best to breath where there are caesuras so then the melodic line is not interrupted. If a caesura is not easily noticeable and the instrumentalist is at a lost as to where to breath, the composer would usually understand and thus institute breathing signs to avoid a musical setback. In the early seventeenth century, solo songs began to increase in recitative and monody. Emilio de’ Cavalieri was an Italian composer who placed several breath markings in the shape of an “s” within his music which was normally placed above the last note of the melodic line (Figure 1).

Figure 2 Emilio de’ Cavalieri “Aria cantata e sonata, al modo antico” with two flutes and solo tenor.

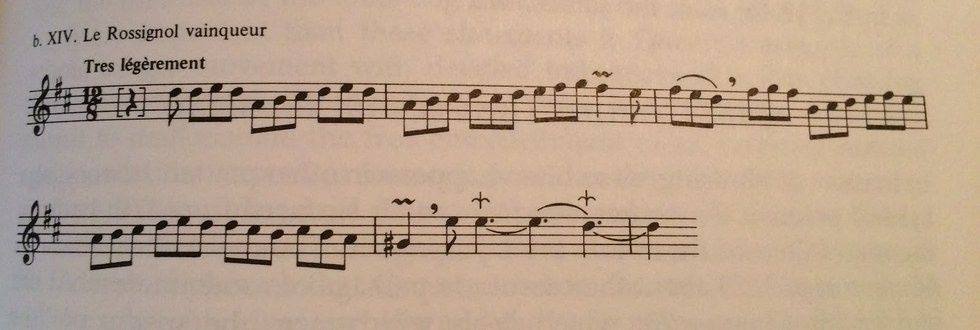

In Heinrich Schutz Psalmen Davids (1628) he later used a vertical stroke to indicate a breath should be taken at the caesura and would do so at the end of every verse. As the breath mark continued to improve, Le Bègue Troisième livre d’orgue (ca. 1700) also used the vertical breath mark when the phrasing was nonuniform or when the ending was unclear. In François Couperin’s third book of Pieces de clavecin (1722) he introduced what we now use in modern repertoire the large comma ❜ indicating the end of the melody or phrase (Figure 2). Phrasing was very important in terms of the baroque style for woodwind, brass, and other instruments such as the organ, harpsichord, lute, violin, etc. Alongside mastering the proper use of ending a phrase, articulations of such notes were required.

Figure 3 Francois Couperin Pieces de clavecin (1722) Très légèrement

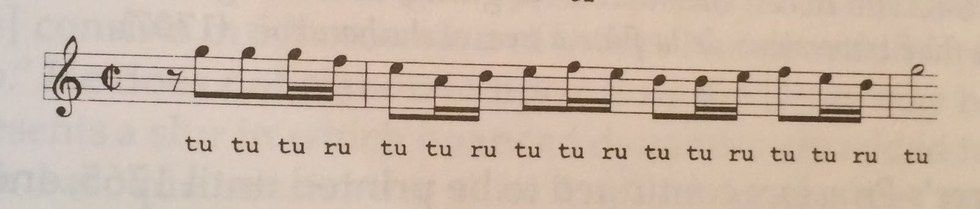

For the flute the use of syllables in tonguing helped maintain the air flow when executing a soft or loud attack. To produce a hard or soft attack, the syllables tu and ru were often used when given a slight uneven rhythm called notes inegales. Though seen as equal notes, precise notes were used to be played in a shorter rhythm compared to the previous note. In Figure 3, Jacques-Martin Hotteterre wrote Principes de la flûte traversière, de la flûte à bec, et du hautbois (“Principles of the transverse flute, recorder, and the oboe”) where he showed the proper articulation of 1707.

The most common syllable that is used when articulating half notes, whole notes, quarter notes, some eighth notes, and notes that needs to be repeated or leaped is tu. When the note is diatonic, it is suggested to use the articulation ru, but it all depends on the tempo. In Figure 3, the meter is suggesting a faster tempo so the articulation will need to be more detached, and that’s where the syllable tu comes into play. If you notice, ru has been placed on the diatonic notes (the second sixteenth note) to better connect it to the next note which will need to be tongued as tu.

Figure 4 Tu and ru when tonguing, as shown from Jacques-Martin Hotteterre’s Principes de la flûte traversière, de la flûte à bec, et du hautbois (“Principles of the transverse flute, recorder, and the oboe”)

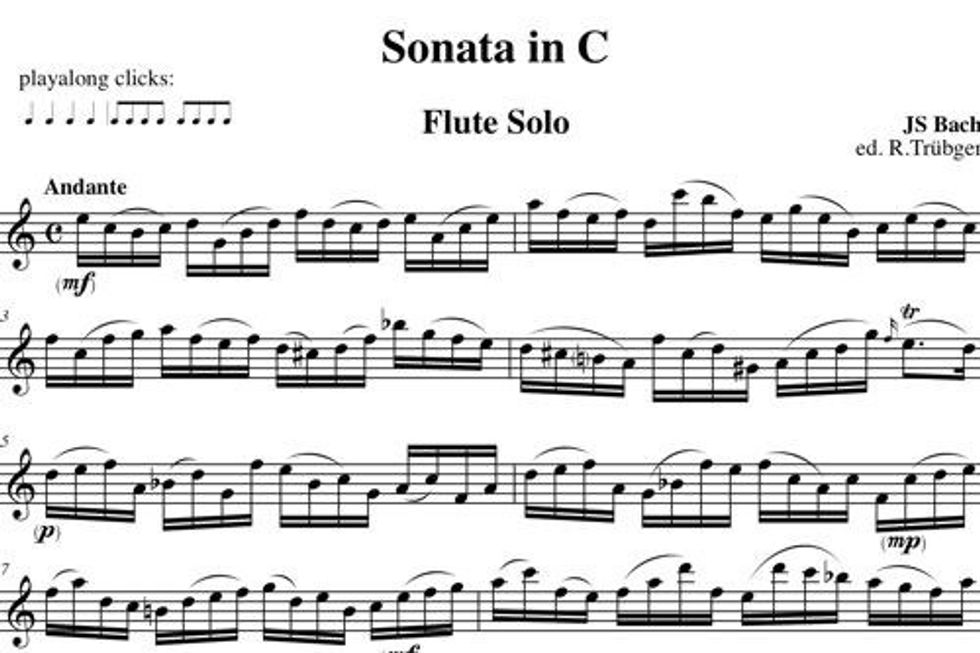

Great flute composers has incorporated all of these characteristics of the baroque style into their pieces, and the flautist at the time made sure to execute them with the best tone, style, and articulation. Johann Sebastian Bach was a world renowned composer that was truly known for his harpsichord and organ compositions. He did not nearly compose as many flute pieces as his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, but the repertoire he produced for the instrument was nothing less but sublime. J.S. Bach composed 7 flute sonatas which all embodied the need of emotion and stylized dance within his pieces. Sonata in C Major, BWV 1033 filled the page with sixteenth notes and slurs with little to no dynamics. Bach was never really known for adding breath marks within his compositions, and leaves little room for cesuras. This is what makes the piece all the more difficult because it is imperative to not break a phrase throughout the entire piece. A good place to take a breath is definitely between the c2 and e2 of measure 2, and another big breath at measure 3 between the B-flat2 and the g2 is required to make the transition into measure 5 seam seamless. You want to breath as little as possible within this piece because it is supposed to imitate the continuous motion of the violin. It is also encouraged that the performer included agréments within the piece and one of the places to add an embellishment is beat one of measure 4 on d2.

Figure 5 Flute Sonata in C Major, BWV 1033 Johann Sebastian Bach movement 1 Andante

The eighteenth century was most important because it signified the origin of the flute. It also brought forth a variety of composers, composition and performance styles, and compelling musical works. It was within this century that the flute was given its most notable characteristics, such as key placements and pitch tendencies, varying depended on the style of the flute. Additionally within this era, composition and performance styles began to grow from simple configurations to an elaborate flute design. As flute performance became more dominant, there arose many notable composers such as Quantz and Vivaldi. Collectively considered, the eighteenth century can arguably be named one of the most influential musical times because it helped shaped modern day flute performance.

References

Carter, Stewart, and Jeffery T. Kite-Powell. “5: Woodwinds.” A Performer’s Guide to Seventeenth-Century Music. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2012. 70-77. Print.

Cyr, Mary, and Reinhard G. Pauly. Performing Baroque Music. Portland, Or.: Amadeus, 1992. 21-102. Print.

Gemeinhardt. “Flute History.” Flute History. N.p., 2014. Web. 18 Nov. 2016.

Hankin, Chris. “Building A Flute Library: Baroque Sonatas.” Just Flute Blog. WordPress, 02 Dec. 2011. Web. 18 Nov. 2016.

Neumann, Frederick, and Jane R. Stevens. “19: Theory of Phrasing.” Performance Practices of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. New York: Schirmer, 1993. 259-65. Print.